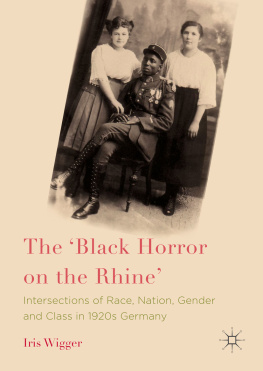

1. Introduction

1.1 An Outrageous Humiliation and Rape of a Highly Cultivated White Race by a Still Half-Barbaric Coloured. Mapping the Black Shame Campaign

On the 10 January 1920, the Treaty of Versailles came into force. It laid down the occupation of strategically important areas of Germany by the Allied Forces for a period of 15 years; the occupation affected mainly regions left of the river Rhine, amongst them the cities of Coblenz, Cologne and Mainz. The French government used black troops from its African colonies in, for example, Tunisia, Morocco, Madagascar, Algeria and Senegal as part of the French occupation troops.

The presence of these non-white African soldiers in the German Rhineland after the end of the First World War provoked massive protests in Germany, Europe and the United States. Since 1919, they were stereotyped in racist terms as primitive savages who committed predominantly sexual crimes on a massive scale. Despite provably committing fewer crimes than other divisions of the Allied troops, they were frequently represented as violent beasts, against which one needed to protect the German people, the white race and culture .

However, it is also beyond doubt that conflicts did occur in the context of the French occupation on the Rhine and so did isolated proven criminal offences and acts of violence committed by colonial soldiers. Christian Koller closely looks at the relation between the Rhenish population and the colonial soldiers taking part in the Allied occupation of the German Rhineland using local Administration files from Worms and Wiesbaden. These contain evidence of conflicts as well as of a fairly normal social coexistence in the context of the occupation situation.

Complaints from Worms are often referring to bagatelle cases such as unauthorised cycling or football playing. Moreover, some cases of attacks from Moroccan soldiers against Germans and physical conflicts are reported. Complaints about sexual atrocities , however, are rare, and the Wormser senior mayor later considered the Senegalese regiment a well-disciplined troop.

In Wiesbaden, reports are referring to conflicts, the damage to property, brawls and other crimes, amongst them some of a sexual nature, and they also note four cases of death caused by colonial soldiers. Despite the fact that this number of deaths was smaller than that of deaths caused by white French troops, they resulted, according to Koller , in a tense relationship between the population of Wiesbaden and the colonial troops . Besides such conflicts, reports also referred to friendship-based contacts between the German population in the occupied territories and the colonial soldiers.

Koller considers the stories spread by the propagators of the campaign as indisputably invented atrocities of the German unofficial propaganda . He also dismisses official German propagandas claim of large-scale black atrocities as questionable, based on the lack of precision and the sameness of several statements in the collections of cases released by the authorities above the local county districts.

On the basis of Allied investigations of these accusations, we can conclude that the sexual crimes of colonial soldiers were single, isolated cases, rather than, as propagated in the campaign, a large-scale phenomenon and problem. However, regardless of the fact that colonial troops made up less than half of the French occupation troops, and did, as Koller argues, not commit atrocities above the average compared to other troops present, the protests focused for years predominantly and nearly exclusively on the Black Shame.

The history of the Black Horror is insofar predominantly a history of propaganda, the history of a campaign, unleashed under this title to protest against the deployment of French colonial troops in Germany. The use of colonial troops in Europe had already been a matter of intense controversy before and during the First World War, After the end of the war, protests against these troops became highly popular and culminated, with the help of modern mass media , in a massive international racist campaign that defamed the Africans as black brutes who would, driven by their excessive sexual instincts, racially contaminate the German people . The campaign found many supporters in Germany, several other European nations and the United States.

Contemporaries accused those savages of presenting a gruesome danger Such severe racist rhetoric had clearly calculated propagandistic dimensions. When German authorities and politicians called for public protest against the use and the atrocities of coloured troops , they attempted politically to discredit France internationally, to put pressure on the French government and to achieve an alleviation of the hardships associated with the Allied occupation .

However, the use of black troops was not only under attack from German authorities, politicians, a wide range of organisations and the majority of the German press. The Black Shame also became a popular issue in the bulk of popular media , which rapidly spread populist and scandalising images of the Black Horror on the Rhine. I shall hence argue that the campaign developed a dynamic of its own, which was neither foreseen, nor controllable.

On a political level, the campaign was supported by different governmental authorities and political associations, many of them linked with the authorities, and the vast majority of political parties in the German Parliament. Different campaigners criticised the Black Shame as an act of French violent rule (Gewaltherrschaft) over Germany and included the German Office for Foreign Affairs (Auswrtiges Amt), the Reichsheimatdienst, the Rheinische Volkspflege (Rhenish Peoples League) and all parties of the German Parliament with the exception of the left-wing USPD and the Communist K.P.D.

The German government protested against the use of colonial troops in late 1918, following warnings of the German Colonial Society (deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft), which condemned their use in Europe as a threat to European civilisation .

Well-known figures of German public life, sharing these concerns, included, for example, Prince Max von Baden, Professor Lujo Brentano , Count Max Montgelas and General Paul von Hindenburg . They emphasised that the black plague was not a purely German but an international problem, concerning Germany as well as Europe and the entire occidental culture . They demanded solidarity with the oppressed German people and attacked the garrisoning of coloured, racially alien troops in Europa as an atrocity against the whole of Europe.

The campaign against the Black Shame spread rapidly in spring of 1920, following a period of only sporadic protests in the press and on a political level at the end of 1919. The German press frequently protested, referred to detailed terror reports about the shame of the black occupation,

This first wave of protests in the German newspapers was associated with an incident in the city of Frankfurt involving Moroccan troops taking part in the French occupation of the city. On 6 April 1920, some of these troops had opened fire against German protesters who hassled them.

The German press and the German Parliament condemned the Moroccan troops. In a parliamentary discussion a couple of weeks later, all parties with the exception of the USPD agreed on a resolution to the government that criticised the abusive use of Coloureds as non-effaceable Shame. The representatives of the government joined the parliamentary protest , and the minister of the German Office for Foreign Affairs proclaimed that the use of black troops was a great danger, not least from the perspective of the German peoples racial hygiene .