Jacob Collins - The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968

Here you can read online Jacob Collins - The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc., genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

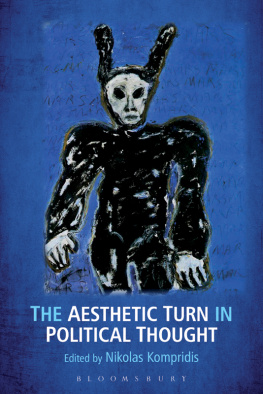

- Book:The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jacob Collins: author's other books

Who wrote The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Anthropological Turn

INTELLECTUAL HISTORY

OF THE MODERN AGE

Series Editors

Angus Burgin

Peter E. Gordon

Joel Isaac

Karuna Mantena

Samuel Moyn

Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen

Camille Robcis

Sophia Rosenfeld

French Political Thought After 1968

Jacob Collins

Copyright 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used

for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Collins, Jacob, author.

Title: The anthropological turn : French political thought after 1968 / Jacob Collins.

Other titles: Intellectual history of the modern age.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2020] | Series: Intellectual history of the modern age | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019032104 | ISBN 978-0-8122-5216-3 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Benoist, Alain dePolitical and social views. | Gauchet, MarcelPolitical and social views. | Todd, Emmanuel, 1951 Political and social views. | Debray, RgisPolitical and social views. | Political scienceFranceHistory20th century. | Political anthropologyFrance. | FrancePolitics and government1958 | FranceIntellectual life20th century.

Classification: LCC JA84.F8 C64 2020 | DDC 320.01dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032104

For Naomi

The 1970s in France were years of malaise. The 1960s had been monumental by comparison: The economy was growing at an extraordinary rate; Charles de Gaulle, a kind of living myth, was president; young radicals were protesting Western imperialism in North Africa and Southeast Asia; and a social revolution nearly toppled the government in 1968. The cinema of the New Wave, the philosophy of Louis Althusser, the fashion of Yves Saint Laurentto name only a fewwere the high cultural achievements of this decade. The 1970s, in contrast, were marked by economic recession, political fragmentation, anti-immigrant sentiment, and the uninspiring liberal presidency of Valry Giscard dEstaing. This change of mood had underlying structural causes: The oil shock of 1973 signaled the end of a thirty-year period of unprecedented economic growth, and production began shifting away from manufacturing toward a service-oriented economy. Politically, the many radical groups and movements that were created in the late 1960s were, by the mid-1970s, disbanded, their members either dropping out or cleaning up their act to join more established political parties. Their hope of building new kinds of political community after 1968more popular and egalitarianwere crushed in this atmosphere.

There was, nevertheless, one promising development: In 1972, Socialists and Communists agreed to put aside their differences and run on a joint platform, striking a pact that became known as the Union of the Left. Shortly before the 1978 elections, however, the Communists abruptly withdrew and the coalition fell apart. The right-wing vote had already been split between followers of de Gaulle, and President Giscards liberal coalition. And now with the left-wing vote forked too, the electorate was divided almost evenly four ways, leading to a political deadlock. Thus, with the slowdown of capitalist growth and the splintering of politics, the sense of optimism that animated the 1960s spirit of protest evaporated and indeed left a void in the heart of French politics. The philosopher Jean Baudrillard offered an appropriate epitaph: The loss of meaning, the end of history, the agony of politics, the transparency and indeterminacy of the social itself, the power of simulation, the omnipresence and obscenity of the media.

While many things were dying out in this decade, new things were taking shape too.

By the following decade, the indeterminacies of the 1970s began to harden, and it became clear to many that a new France was in the making. After a period marked by high unemployment, stagnant wages, and high inflation, French people were ready for a change. In May 1981, they elected for the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic a Socialist president, Franois Mitterrand. After the bitter infighting of 1977 and 1978, this victory brought a momentary surge of excitement to the Left. Mitterrand promised a sweeping redistributive agenda that would transform society and break with capitalism. His demand-side economic policies, however, quickly exacerbated existing problems: Deficits soared as unemployment and inflation continued to rise. After less than two years in office, Mitterrand reversed coursethe famous U-turnand implemented a number of anti-inflationary austerity measures. Wages were frozen and transfer payments were no longer increased, contrary to Mitterrands promises. Even if social spending remained high by the standards of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, the French had very little to show for it by the 1990s. During Mitterrands first seven-year term, productivity declined, unemployment continued to rise, and social conflict was aggravated rather than pacified. In addition, membership in the mass parties of the Left, not to mention unions, had already been falling off precipitously since the late 1970s.

Moreover, these years were characterized by a recurrent failure by the major parties to find a stable ruling coalition. The 1986 legislative elections delivered sweeping victories for the Right, forcing Mitterrand to name the conservative Jacques Chirac as prime minister. This was the first time a cohabitation scenario had arisen in the Fifth Republic, leaving one party in control of the executive office and another in charge of the legislature. In 1988, the parliamentary majority shifted back to the Left, and then again to the Right in 1993. The formation of solid ruling blocs has proved fleeting ever since.

Political discourse likewise took on a more divisive, embittered tone. For the first time, Jean-Marie Le Pens race-baiting party of the extreme Right, the Front national (FN), began to achieve high returns in local, national, and European elections in the mid-1980s. With the simultaneous formation of anti-racist groups like SOS Racisme, the language of race, citizenship, gender, and immigration took on new importance in French public debate. On the one hand, the centrality of these issues to French discourse had been made possible by the social revolution of the 1960s, which rendered visible all the ways that the apparent consensus of the postwar miracle years had excluded women, gays, immigrants, people of color, and the incarcerated. In doing so, it demanded that new logics of the social be considered, ones that were more inclusive and egalitarian. On the other hand, the effects of this revolution were being felt at the moment when economies were slowing and budgetary pressures increasing. Once austerity measures took hold in 1983, public debate quickly assumed that some groups were entitledat the expense of othersto a diminishing stock of welfare provisions. This was the context in which Le Pens movement of the Far Right gained a national foothold, pitting ethnic groups against one another and arguing that immigrants ought to be the first group excluded from these benefits. The response of Mitterrand and the Socialist Party (PS) was to push for tolerance. They defended the right to difference for various subgroups, and they called for initiatives supporting regional and ethnic diversity. Thus it happened that economic and cultural pressuresthe recession and the end of empireconverged to form a new framework for talking about identity and race in the early 1980s.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968»

Look at similar books to The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Anthropological Turn French political thought after 1968 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.