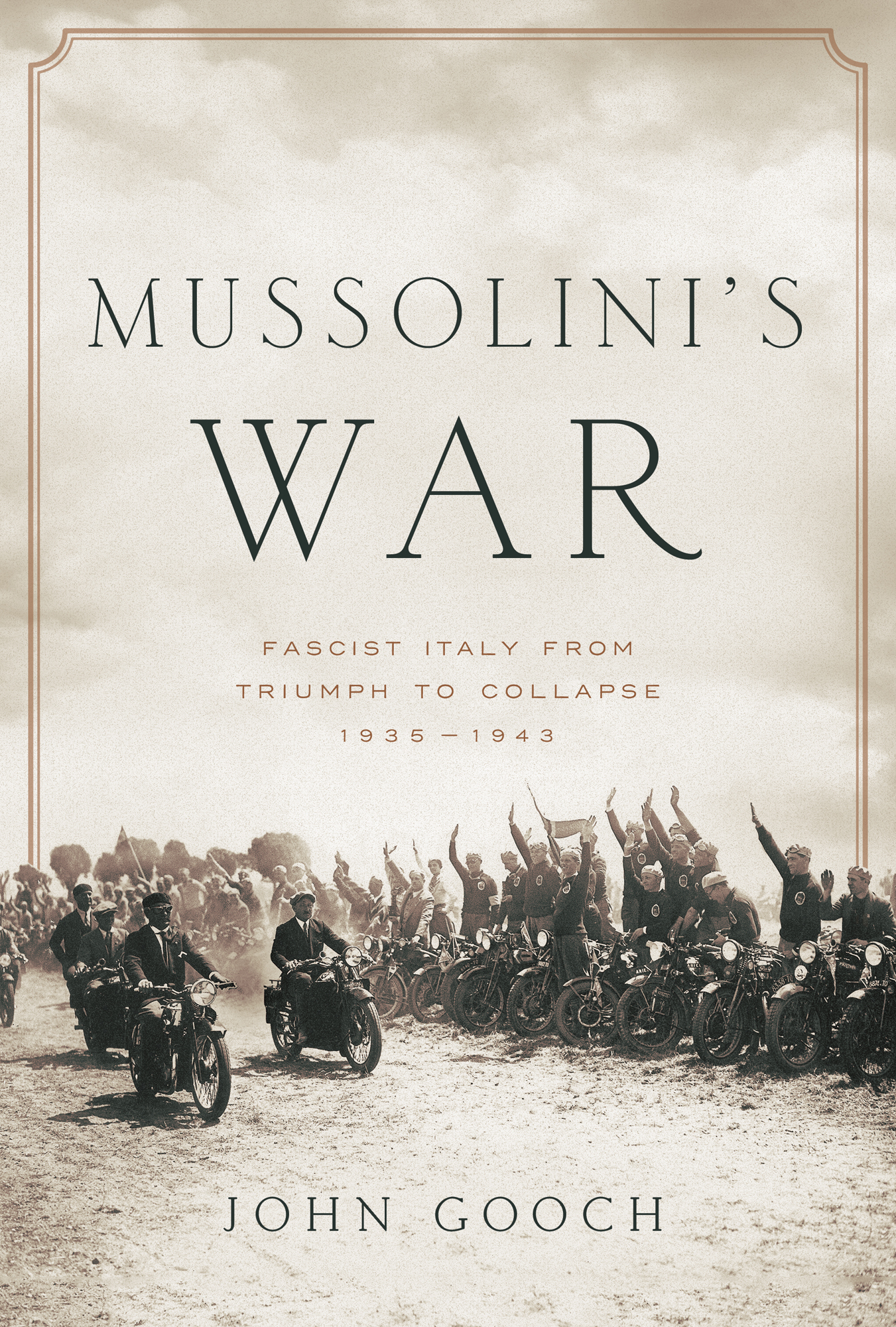

John Gooch - Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943

Here you can read online John Gooch - Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Pegasus Books, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943

- Author:

- Publisher:Pegasus Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The character of a leader is a large

factor in the game of war

General William Tecumseh Sherman

Once again I am deeply grateful to the personnel who man the Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dellEsercito in Rome for their help and support while I was researching this book. Colonel Filippo Cappellano, first as caparchivio and latterly as Head of the Office, a distinguished historian in his own right, has welcomed me on numerous occasions and shared with me his unbounded knowledge of the archives. His predecessor, Colonel Cristiano Dechigi, was no less supportive in his turn. Lieutenant-Colonel Emilio Tirone, currently head of the archive, has been and is no less welcoming and has given me much unobtrusive but invaluable assistance. Trawling through the archives themselves was made infinitely easier with the advice and guidance of the principal archivist, Dottore Alessandro Gionfrida. My thanks go to him, to his deputy Dottore Filippo Bignato, and to the unfailingly cheerful and friendly staff who ferry the files to and fro. With the help of caporale maggiore Claudio Piddini, and some much-appreciated cups of espresso coffee, I was able to make a brief raid on the photographic archives a source of extraordinary depth and richness which remains under-exploited by historians.

My entry into the Italian Air Ministry was made simple and straightforward thanks to the friendship, help and hospitality of Lieutenant-General Basilio Di Martino. The head of the Ufficio Storico dellAeronautica Militare, Colonel Luigi Borzise, opened its resources to me without hesitation. He and his staff, Dotoressa Monica Bovino and Signore Marcello Neve, were friendliness personified and made my brief time with them both productive and delightful.

Getting into Service archives in Italy requires jumping through bureaucratic hoops. Signora Palmina Cerullo of the British Embassy in Rome has come up trumps every time yet another of my requests for help has landed on her desk. Thanks, Palmina.

In Genoa, Dr Gianni Franzone, director of the Centro Wolfsoniana, kindly found me room and time in which to consult his archive. And at Castiglione delle Stiviere, Professoressa Dr Silvana Greco and Professor Giulio Busi, directors of the Fondazione Palazzo Bondoni Pastorio, were the most hospitable and kindly of hosts.

My visits to the outstation of the Imperial War Museum at Duxford were among my most enjoyable outings thanks to the presence there of Stephen Walton as Senior Curator. Stephen provided everything a researcher could want: swift and comprehensive guidance through the holdings, ready help when needed, relaxing surroundings even coffee and a biscuit!

In Rome, long-time friends Dr Ciro Paoletti and Professor Andrea Ungari made my visits even more of a pleasure than they would otherwise have been. And in London Drs. Jenny and Michael Sevitt provided home comforts while I visited the ever-efficient National Archives at Kew.

Assembling the materials for a book such as this is not straightforward and I am deeply grateful to friends old and new for helping me do so. My warmest thanks go to Professor Holger Afflerbach; Dr Fabio De Ninno; Dr Jurgen Foerster; Dr Emilio Gin; Dr Richard Hammond; Professor MacGregor Knox; Dr Jacopo Lorenzini; Professor Evan Mawdsley; Dr Steven Morewood; Professor Rick Schneid; Dr Matteo Scianna; Dr Brian Sullivan; and Dr Nicolas Virtue.

Many years ago a professor in my college remarked that historians should not marry. For me at least, he was wholly wrong. Ann has lived patiently with Italian military matters for a very long time, managing our lives together here in England and in Rome. Without her as a partner this book would not have been written, so it is at least as much hers as it is mine.

Commissioned as a cavalry officer, Ambrosio served as a divisional staff officer during the First World War and a divisional and then corps commander in the years that followed. In 1939 he was given command of 2nd Army on the Yugoslav border, leading the Italian offensive against the Yugoslavs in April 1941. Exchanging posts with Mario Roatta, he became chief of the army general staff in January 1942. On 1 February 1943 Mussolini appointed him chief of the armed forces general staff. A dyed-in-the-wool monarchist, he played a major part in the plotting that led to Mussolinis downfall after repeated but fruitless attempts to persuade Mussolini to change course. On 89 September, after the announcement of the armistice, he left Rome along with the king, Badoglio and others, serving under the rump Italian government as inspector-general of the army until November 1944.

Am joined the Italian Military Intelligence Service (Servizio Informazioni Militari SIM) in 1921, serving first in the counter-espionage centre at Turin and then in Vienna and Budapest. Leaving SIM in 1929, he held a command post in Perugia and then taught at the Air Force Academy at Caserta from 1933 to 1935. Promoted colonel in 1937, he commanded an infantry regiment and served first as a divisional and then as corps chief of staff. Recalled to SIM as vice-chief with Mussolinis approval at the beginning of January 1940, he was appointed head of SIM on 20 September 1940. By the end of 1941 he commanded an organization of 1,500 officers, non-commissioned officers and specialized troops, double the size of the one he took over. He was removed by Badoglio on 18 August 1943.

A faithful follower of Badoglio, Armellini commanded an Eritrean battalion during the reconquest of Libya. In November 1935 Badoglio made him operations chief in Ethiopia. From 1936 until 1938 he served as military commander of the Amhara district. Following divisional commands in Italy, he served as Badoglios chief staff officer at the Comando Supremo from June 1940 until he was replaced in January 1941 following his masters fall. He commanded the La Spezia infantry division and then XVIII Corps in Dalmatia and Croatia until he was replaced in July 1942 following a clash with the civil governor of Dalmatia, Giuseppe Bastianini. When Mussolini fell on 25 July 1943, Armellini was tasked by Badoglio with dissolving the Fascist militia (Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale) and incorporating it into the army. After the armistice he joined the resistance in Rome, heading the clandestine military front there from March 1944.

Badoglio enjoyed a meteoric rise during the First World War, climbing from lieutenant-colonel to lieutenant-general in only two years. His XXVII Corps front collapsed during the battle of Caporetto (24 October 1917), giving rise to accusations of failure and then of a cover-up which dogged him throughout his life as they continue to do. After serving as ambassador to Brazil between 1923 and 1925 he became army chief of staff and then Capo di stato maggiore generale (chief of the armed forces general staff) from 1925 to 1940. Between 1929 and 1933 he was governor of Libya and then from November 1935 to May 1936 he directed the war in Ethiopia, all the while still holding his position in Rome. He both solicited and received rich rewards: the king made him duke of Addis Ababa in July 1936. His direction of military affairs was generally unimpressive. Uncharacteristically, he openly criticized Mussolini after the Greek debacle in November 1940 and lost office as a result. His deep-seated dislike of the Germans was probably only exceeded by his visceral hatred of Cavallero, in whose death he may have had an indirect hand. Appointed head of the government on 25 July 1943, he fled Rome for Brindisi with the king and others on 89 September 1943, continuing to head the rump Italian government until June 1944.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943»

Look at similar books to Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mussolinis War: Fascist Italy from Triumph to Collapse: 1935-1943 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.