1

Art in Prison

Long before art therapists worked in prisons providing clinical services, the arts in corrections flourished. Ursprung (1997) recognized that prison art is probably as old as the institution of prison itself (p. 18). The writings of Plato and Socrates were inspired by their respective incarcerations (Rojcewicz, 1997), and gladiators enslaved in the Pompeii arena in the first century scratched graffiti into the walls of their imprisoning barracks (Kornfeld, 1997). Many artistic victims of Nazi Germany imprisoned in various concentration camps created drawings and paintings of what they saw, as an escape and as a way to bear witnessnever mind that if they were caught doing so would have resulted in their immediate death (Gussak, 2004 a). The excavation of a Pennsylvania prison built in 1829 yielded inmate handicrafts, specifically wooden toys, figurines, and gaming pieces (Ursprung, 1997). was by an unknown artist, discovered during that excavation; on the end of a matchstick he carved a replica of the sculpture of William Penn that sits atop Philadelphias City Hall.

Many famous artists and writers completed great works of art while imprisoned in asylums and early forms of penitentiaries (Rojcewicz, 1997). In the 1780s, well-known painter Jacques-Louis David painted some of his celebrated works, including his self-portrait, while imprisoned for his political views. Oscar Wilde and Franois Villon wrote and composed poems about their respective prison experiences. Johnny Cash reminded us of just how important and prevalent music is within the walls, Lil Wayne, Tupac Shakur, and Prodigy all composed some of their music while locked upsome of which was about their experienceswhile Merle Haggard played in a country band while in San Quentin.

This has developed into more systematic arts in corrections programming. What has naturally emerged is the clear understanding that not only is art making recreationally beneficial for the prison population, but that it would lead to one of the most advantageous and therapeutic interventions inside.

Overcoming Limitations

Clearly, there is a natural tendency for artistic and creative expression in prison settings (Brown, 2002; Kornfeld, 1997; Ursprung, 1997). Correctional institutions are filled with energy needing an outletcertainly a creative outlet is much preferred over other forms of cathartic expression. As Ursprung further stressed:

The incarceration experience, one of sensory deprivation, is a world of imposed controls, rigid regulations, tedium, minimum allowable risk, and consistent inconsistencies. It appears that the creative process [art making] is an apt coping mechanism in order to survive such an oppressive dys-functional milieu, especially to derive some sense of order out of chaos.

(1997, p. 17)

Inmates find unique methods to create in order to overcome the limitations they experience. While some institutions have supported some variations of arts programming, oftentimes inmates rely on their own talents to create: envelopes are decorated and then bartered by talented inmates to send letters home, handkerchiefs are covered with intricate designs and portraits sold to other inmates to give to their loved ones as mementos, and of course many inmates sport intricate tattoos designed by those inside (Gussak & Ploumis-Devick, 2004). The prison system comprises several hierarchical layers, not the least of which is the artist whose abilities are much esteemed; inmates who create good art earn respect and friendship from others (Kornfeld, 1997). Even when limitations seemingly make it almost impossible to create, those inside still find ways to make something out of nothing, oftentimes rising above the ugliness inside.

Strings Are Attached

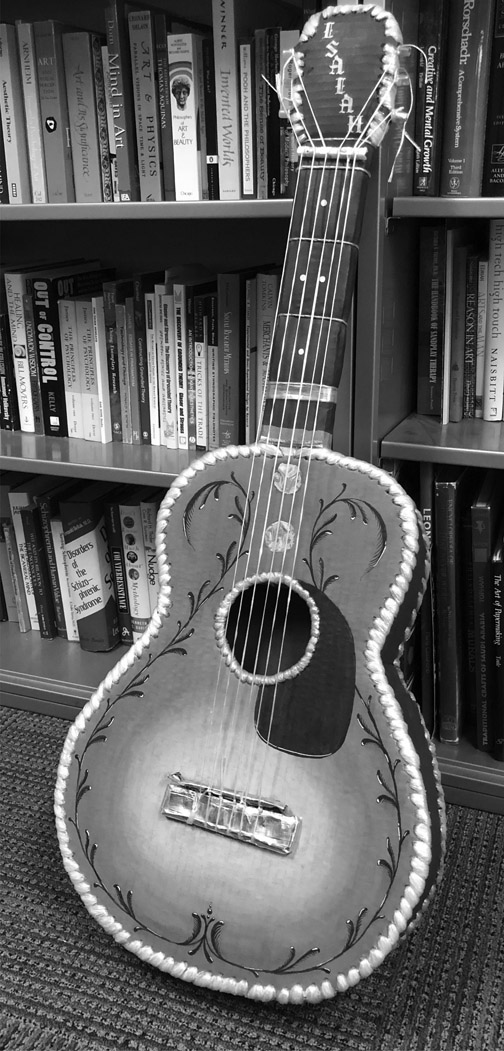

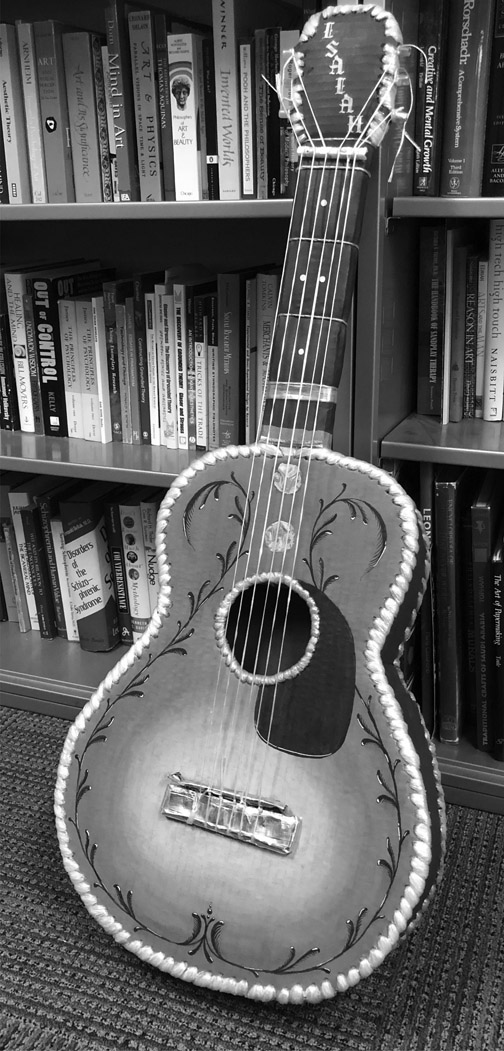

Several years ago, I received an email from a long-time friend and colleague, Laura Bedard, formerly professor of criminology at Florida State University, deputy secretary of Floridas Department of Corrections, and warden for several institutions. Known for her forward thinking and strong support for programming and education, she has been a strong advocate for the arts in prisons. She told me that one of her officers confiscated an art piece completed by an inmate. Considered contraband, the officer was set to destroy it. She rescued the piece and sent it to me for safekeeping [].

The guitar stands around three feet tall and is constructed from discarded cardboard, artfully folded and painted, sewn together with stretched white plastic garbage bags. Its strings are also made from the same trash bags, stretched and then connected tautly to tuning pegs made from broken disposable ink pens. The bridge and frets are made from candy bar foils. While there was no information provided on how it was painted, the brown looks like shoe polish, the yellow and orange appear to be colored pencil, and the black seems to be pen ink.

Dr. Bedard does not know who the artist was; the only clue we have is the common name on the guitar head, done in stylized white graffiti-like lettering, which could either represent the artist or the artists loved one. Unfortunately, there was no way to tell who it was or what happened to him.

There was no art programming in this facility. This piece was constructed in the inmates free time, likely in secret. As a resident of this system, he likely knew it was contraband. He did not make the piece for notoriety, as he kept it hidden, likely not showing it to many people.

This piece, in all its tangible form, emphasizes this drive to create insider art.

Outsider/Insider Art

Art Brut [Raw Art], commonly known as Outsider Art, refers to work created by those on the fringes of society, outside the mainstream art world. Dubuffet (1949) first conceived of this form as its own genre, focusing on the art completed by psychiatric patients, vagabonds and those he considered eccentric. Cardinal, an expert of Outsider Art (1972), considered the works of these untutored artists as honest yet nave, while Dubuffet recognized their output as pure yet crude (Macgregor, 1989). Some outside artists are driven to create even despite their lack of ability or talent. For similar work created in prison, Ursprung coined the term Insider Art (1997).

Many inmates inside are driven to create, despite knowing that the pieces they make outside of a sanctioned program might be confiscated and destroyed. Using the creative process to escape from their surroundings, many inmates will create regardless of their limitations.

As I was writing this, it conjured up a memory from long ago. In the mid-1990s, when I was a young art therapist, I was walking down the mainline of a California prison with a colleague when we saw an inmate carrying a rather large sailing ship, heavy enough for it to be a visible struggle to transport. It was made out of hundreds of tongue depressors, with its sails made from fragile toilet paper. We stopped him so we could take a closer look. It was one of the most intricate sculptures we had ever seen. He was justifiably proud of it; he had spent many weeks building it from these discarded pieces of wood. When talking to him, he revealed he had no artistic training, and simply felt compelled to make it. His sense of accomplishment was palpable.

About a week later we saw him again. We asked him about the sculpture. He told us, in a matter-of-fact tone, that a correctional officer confiscated and destroyed it, as it was deemed a misuse of state property and was therefore contraband (Fox, 1997). He was fairly philosophical about it, shrugging in a matter that conveyed What can you do? Its prison. Personally, I was furious for him; I felt impotent and frustrated. It was not until much later that I realized that he must have known that it was only a matter of time before the piece would be confiscated. What became clear was that it was the act of making it that was important to him. What happened to the piece after was simply an epilogue.

Next page