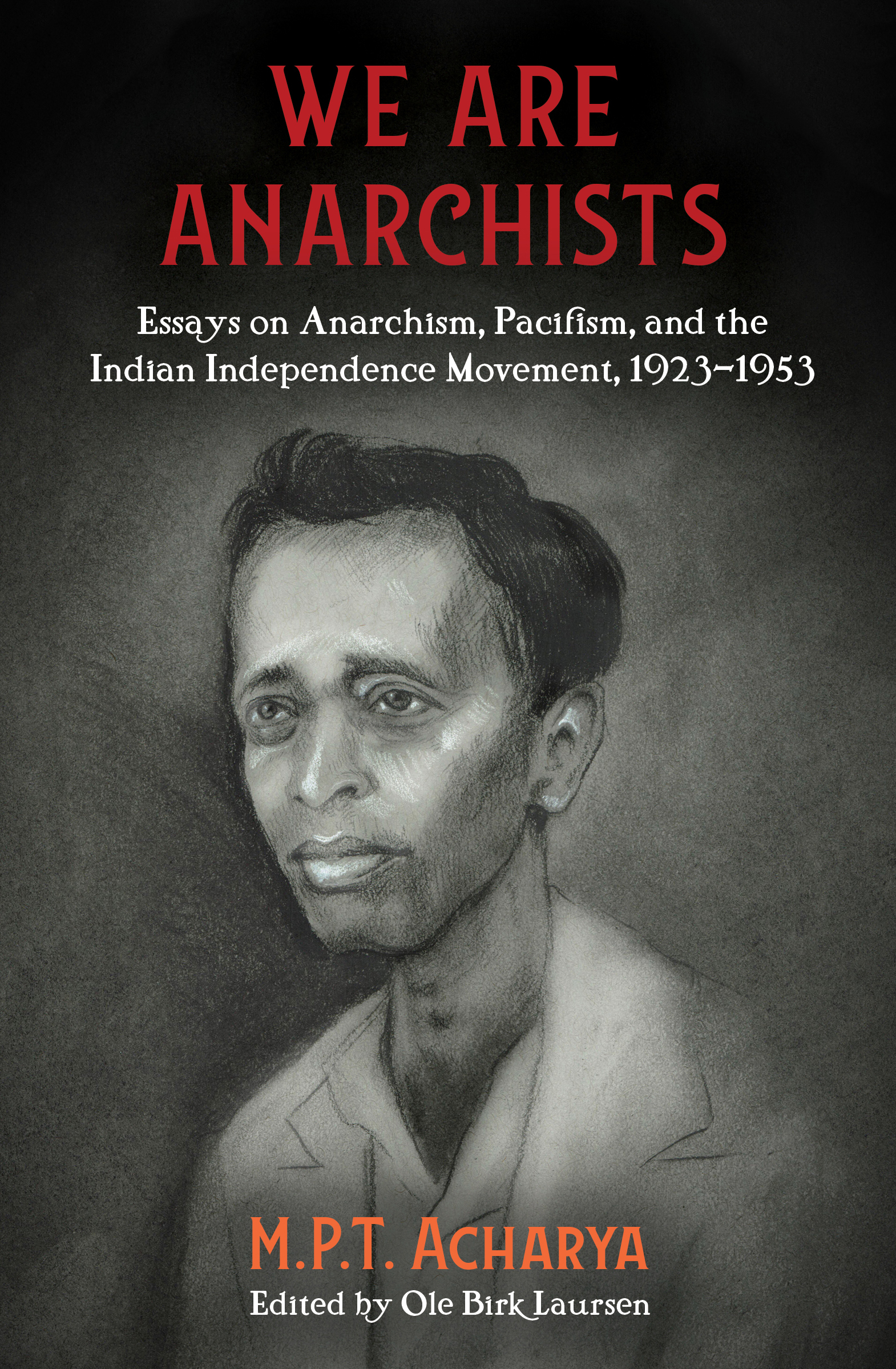

Editing this book has been a labor of love, but I could not have done it alone. I would like to thank Andrew Zonneveld, Charles Weigl, and AK Press for taking on the project, and for their advice, help, and constant support throughout the writing process. I am very grateful to Julia Simoniello for bringing Acharya to life with the beautiful cover image. I am also indebted to Lina Bernstein, Jesse Cohn, Vadim Damier, Andrew Davies, Stephen Legg, Sara Legrandjacques, Pavan Malreddy, and Alex Tickell for their comments and clarifications as well.

M. P. T. Acharya wrote in numerous languages, and one of the greatest tasks has been to find and translate his writings. I am hugely grateful to Sarah Arens, Constance Bantman, Enrique Galvan-Alvarez, and Julia Scheib for their invaluable help with those translations.

Any historian relies on archives, and archivists and librarians are key to unlocking those archives. I am particularly thankful to Stefan Dickers at the Bishopsgate Institute, London; Jacques Gillen at Mundaneum, Centre darchives de la Fdration Wallonie-Bruxelles & Espace dexpositions temporaries; Katherine Schmelling at Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University; Carol Stewart at the Anderson Library, University of Strathclyde; the staff at the British Library, London; the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam; and the Bibliothque nationale de France, Paris.

Lastly, I could not have done this without Ariane Mildenberg, who patiently listened to many of my stories about Acharya, gave feedback, and offered advice without hesitation.

M. P. T. Acharya: A Revolutionary, an Agitator, a Writer

Born in Madras (now Chennai) , India, on April 15, 1887, the Indian revolutionary Mandayam Prativadi Bhayankaram Tirumal M. P. T. Acharya had a three-decade career in the international anarchist movement from 1923 until his death in 1954. Throughout those years, this Indian anarchistwho was striving on his own in the whole sub-continent to establish a movement, as Albert Meltzer recalledmapped new conceptual territories as he straddled both anti-imperial and anarchist circles. At a time when the Russian Revolution set in motion new hopes for colonized nations and their revolutionaries, Acharyas turn to anarchism is remarkable and stands out against more well-known contemporariesand former comradessuch as Virendranath Chatto Chattopadhyaya and M. N. Roy as well as the Tolstoyan anarcho-pacifist tendencies of Mohandas K. Gandhi. Indeed, in a fitting testimony to Acharya, Meltzer wrote in his obituary:

[I]t was impossible to comprehend the difficulty in standing out against the tide so completely as was necessary in a country like India. It was easy for former nationalist revolutionaries to assert their claims to the positions left vacant by the old imperialist oppressors. This Acharya would not do. He remained an uncompromising rebel, and when age prevented him from speaking, he continued writing right up to the time of his death.

Echoing Meltzer, Vladimir Muos said that Acharya was incorruptible, Victor Garcia called Acharya the most prominent figure among Indian libertarians, and Hem Day summed up: he is not well known to all, even to our own people, for he has neither the fame of Gandhi, nor the fame of Nehru, nor the popularity of Vinoba, nor the notoriety of Kumarapa, nor the dignity of Tagore. He is Acharya, a revolutionary, an agitator, a writer. A prolific writer, Acharyas essays are testimony to a tireless agitator and intellectual within the international anarchist movement, often giving a unique perspective on anarchism, pacifism, and the Indian independence movement. Collected here for the first time, Acharyas essays open a window onto the global reach of anarchism in this period and enables a more nuanced understanding of Indian anti-colonial struggles against oppressive state power, be it imperialist, Bolshevik, or capitalist.

Acharyas wandering movements across India, Europe, the Middle East, the United States, and Russia during the early twentieth century has made it difficult for historians to trace his personal and political development from anti-colonial nationalist to co-founder of the Communist Party of India (CPI) in October 1920 and then, lastly, to international anarchist, as the archives housing his works are scattered across three continents. Aside from Maia Ramnaths acknowledgment that among radical nationalist revolutionaries, none made their identification with the international anarchist movement more explicit than Acharya, there has been no sustained attempt to understand Acharyas anarchist philosophy as both a logical extension of and departure from his anti-colonial revolutionary activities. Therefore, to understand Acharyas turn to anarchism and writings on pacifism and the Indian independence movement, it is useful to provide a biographical sketch of his revolutionary activities from 1907 until 1922.

Indian anti-colonial nationalism and the communist turn, 19071922

In the first installment of his Reminiscences of a Revolutionary (serialized from July to October, 1937 in The Mahratta ), entitled Why I Left India and How?, Acharya describes his flight from India, activities in London and Paris, and his attempt to go to Morocco to join the Rifs against Spain. As it happened, before turning to anarchism, Acharya was already an experienced revolutionary anti-colonial agitator. In collaboration with C. Subramania Bharati, he edited the nationalist paper India in the French-Tamil city of Pondicherry from August to November 1907. When the British Government put pressure on the French authorities in Pondicherry to suppress the Indian revolutionaries in the province, Acharya decided to leave for Europe in November 1908. Arriving in Paris in early 1909, and proceeding to London a week later, he quickly became involved with the nationalists at India House, a hostel set up by Shyamaji Krishnavarma for Indian students and hub for revolutionary activity in the first decade of the twentieth century, then under leadership of the militant nationalist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. After the Indian nationalist Madan Lal Dhingra assassinated political assistant Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie in London on July 1, 1909, the India House group came under heavy surveillance by the Department of Criminal Intelligence (DCI) at Scotland Yard, and many of the Indians left London for Paris.

In an effort to learn armed warfare, Acharya and his friend Sukh Sagar Dutt instead decided to leave for Morocco to join the Rifs in their fight against Spain.

Acharya moved to Berlin in November 1910 to foment revolt among the Indians in the city, and then to Munich a few months later, where he first met Walter Strickland, a staunch supporter of the Indian revolutionaries in Europe and the most anti-British Englishman, as he later recalled. At the suggestion of Ajit Singh and Chatto, and with a letter of introduction in hand from Strickland, Acharya moved to Constantinople (now Istanbul) in November 1911. There he made contact with the Committee of Union and Progress in an effort to secure the support of Muslims against British interests in the region, but no substantial connections were established.