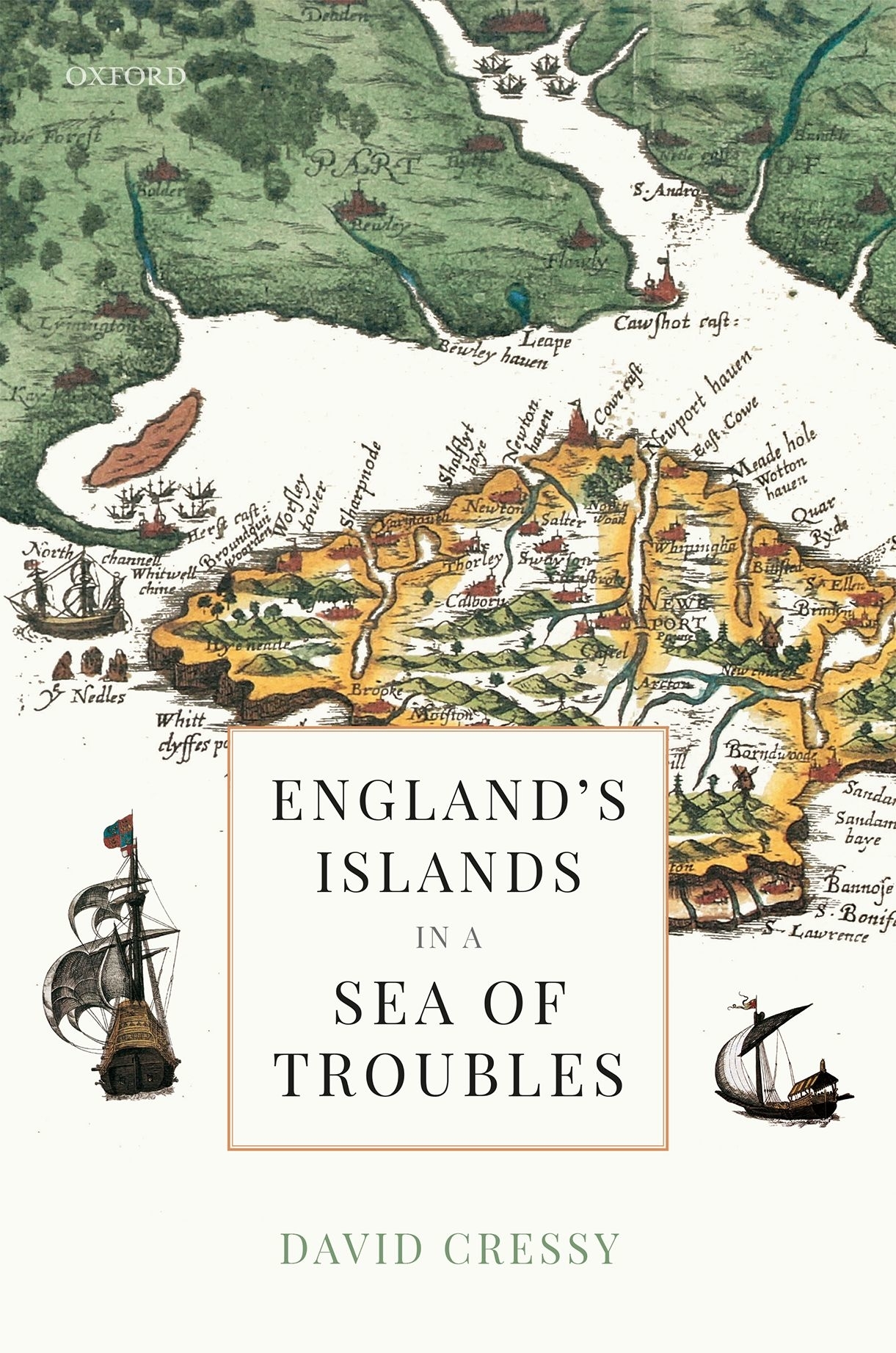

David Cressy - Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles

Here you can read online David Cressy - Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: OUP Oxford, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles

- Author:

- Publisher:OUP Oxford

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

David Cressy 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2020

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020937774

ISBN 9780198856603

ebook ISBN 9780192598523

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198856603.001.0001

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

My core concern as a historian has always been to explore relations between the centre and the periphery, the metropolis and the margins, elite and popular viewpoints, and official and unofficial religion. This curiosity now extends to Englands island fringe. My research changed direction when Vanessa Wilkie, keeper of British manuscripts at the Huntington Library, showed me a recently acquired compendium, in different hands and languages, of protocols, precedents, and correspondence concerning the governance of Guernsey from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. I have been puzzling about it ever since. Darryl Ogier, archivist to the States of Guernsey, helped me understand the context and significance of this volume, and has been generous in directing me to related island sources. Thanks are due too to the archivists and librarians at the Jersey Archives and the Lord Coutanche Library, St Helier. The award of a visiting fellowship at Christ Church, Oxford, enabled me to work on manuscript collections in the Bodleian Library and in London. Continuing access to the databases and resource sharing of the Ohio State University and Honnold Library of the Claremont Colleges allowed me to work at home.

As an early modern social historian, I have accumulated debts to specialists in legal, constitutional, imperial, and military history. Numerous scholars have contributed advice and information, including John Adamson, John Callow, David Farr, Lori Anne Ferrell, Paul Halliday, Tim Harris, Paulina Kewes, Steve Koblik, Jane Ohlmeyer, Jason Peacey, and Tim Thornton. Two anonymous readers for Oxford University Press pushed me to widen my horizons and sharpen my analysis. I am grateful, too, to audiences at the Pacific Coast Conference on British Studies and the North American Conference on British Studies for responding to my papers on island prisons. My greatest debt, as always, is to Valerie Cressy, who read draft chapters, and accompanied me to castles and coastlines in the Channel Islands, the Isles of Scilly, and the Isle of Wight.

Acts of the Privy Council

British Library, London

Bodleian Library, Oxford

Journal of the House of Commons, 10 vols (1802)

Calendar of State Papers Domestic

High Court of Admiralty (TNA)

Historical Manuscripts Commission

Journal of the House of Lords, 10 vols (1802).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Privy Council (TNA)

State Papers (TNA)

The National Archives (Kew)

Englands Islands

Britons of the imperial era conceived their history as an island story and spoke confidently of their island race. H. E. Marshall, Our Island Story: A Childs History of England (1905), was reportedly formative reading of former British Prime Minister David Cameron. The title of Winston Churchills The Island Race (1964) echoes that of the Victorian versifier Henry Newbolt, The Island Race (1898). Patriots of that time attributed English national identity to their offshore location on a moated isle, a homeland fastness from which to range the seas. They belonged to a tradition that attributed Englands national character to her topographical and figurative insularity, and saw islands as places of robust distinction.

English monarchs exercised dominion over a scatter of lesser islands, mostly to the west and south, that were difficult to administer, and sometimes prone to neglect. Yet their strategic positions gave them value and importance that far outweighed their size. Principal among them were the Channel Islands of Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark; the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea; the Isles of Scilly beyond Cornwall; and the Isle of Wight across the Solent. Other parts of the archipelagic perimeter included Anglesey off Wales, Lundy in the Bristol Channel, St Nicholas Island outside Plymouth, and Holy Island on the coast of Northumberland. Edward Chamberlayne, the seventeenth-century compiler of The Present State of England, waxed lyrical about these and other ocean islandsscattered in the British sea like so many pearls to adorn the imperial diadem. Successive governments treated Englands islands as troublesome outliers, or as manageable assets, but also as priceless jewels. Sharing some of the geology of Britains highland zone, they bestrode the edge of the English world.

Relationships between the islands and the rest of the kingdom reflected their legacies of history, constitutional arrangements, opportunities of commerce, considerations of security, distance, and remoteness of location. Their economies tied into maritime, metropolitan, and international networks of commerce and communication. Dependent to varying degrees on the mainland, the islands cherished their exceptions to legal and administrative norms. Though London saw the islands as appurtenances or dependencies of mother England, the islanders more often regarded their homes as privileged places with varying degrees of autonomy.

Each of the islands was fortified, and most had garrisons that served the state. Their harbours and roadsteads were places of strength, coveted by rivals and enemies. At times they were vulnerable to foreign incursion, and all faced threats from pirates or corsairs. They served as places of exile and havens of refuge, and sometimes housed political prisoners, especially in the central decades of the seventeenth century. In civil war they were divided and contested, fought over and occupied. Their civilian inhabitants engaged in lawful and profitable pursuits, such as agriculture, trade, and fishing, as well as less reputable privateering, smuggling, and the plundering of wrecks. Mostly they wanted to be left alone. In the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man, and parts of Anglesey and the Scillies, the common people did not even speak English. Londons agents might be baffled by Jrriais or Guernsiais French, Goidelic Manx, north Welsh, or west Cornish. Island religious culture, though primarily Protestant from the mid-sixteenth century, did not necessarily accord with the established Church of England. External authority was sometimes light of touch. Islanders often argued with each other and caused headaches for their officers and governors. Outsiders were puzzled by insular constitutional anomalies, peculiarities of law, and by claims made by islanders to unique rights and privileges.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles»

Look at similar books to Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Englands Islands in a Sea of Troubles and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.