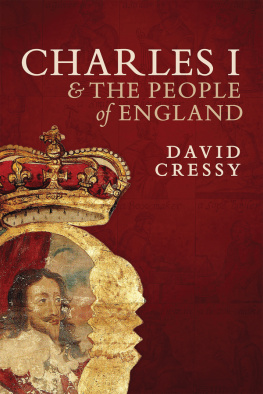

David Cressy - Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder

Here you can read online David Cressy - Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

SALTPETER

An impressive work that throws much light on the multiple social, cultural, political, and technological contacts that affected the development and use of gunpowder weaponry. Particularly important for its assessment of the role of seventeenth and eighteenth-century Britain, a key player in the story.

Jeremy Black, author of War and the Cultural Turn

The Mother of Gunpowder

DAVID CRESSY

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, 0X2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

David Cressy 2013

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2013

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available

ISBN 978-0-19-969575-1

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Writing this book, more any other, has been a journey of discovery. It has taken me into territories and topics that I had not previously explored. It began, modestly enough, with curiosity about the vexation and oppression of the saltpetermen, cited in the Grand Remonstrance of grievances presented to Charles I in 1641. I thought to examine complaints about their activities on the eve of the English civil war, but my enquiries rapidly expanded to embrace the chemistry, industry, and politics of the English saltpeter enterprise, and the military purposes it served, over half a millennium. I have ventured beyond the early modern era, where I am most at home, to range chronologically from the fifteenth century to the twentieth. My work, as always, is centred on England, but in this case it stretches further afield, to the rest of the British Isles, northern Europe, and North Africa, and to British colonies and outposts in Asia and America.

I am beholden to those historians of science, warfare, empire, technology, and law who have introduced me to their specialities. I am grateful to colleagues and students who have helped me unravel the mysteries of saltpeter, and who have stretched my understanding of its social and political context. I have tried the patience of academic chemists who attempted to explain how saltpeter formed and how potassium nitrate worked. I have benefitted from discussion in the graduate seminar in early modern studies at the Ohio State University, the Yale University British Historical Studies Colloquium, and the Ben Franklin Forum at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I particularly wish to thank the following for their insights, suggestions, and corrections: T. H. Breen, John Brooke, Patricia Cleary, Robert Davis, Lisa Ford, James Frey, Matt Goldish, John Guilmartin, Bert Hall, Derek Horton, Margaret Hunt, Michael Hunter, Scott Levi, Christopher Otter, Geoffrey Parker, Kevin Sharpe, Rudi Volti, and Keith Wrightson. Any remaining errors are mine alone.

As a working historian, rooted in the humanities, I find inspiration in the line of Gerard Manley Hopkins: sher pld makes plough down sillion shine. The work gets done, and the results sometimes sparkle. I have always embraced serendipity amid the delights of writing and research, in this case more than usual. Librarians and archivists in Britain and the United States have been generous and professional, as always, but only a chance conversation over lunch at the Huntington in California alerted me to the presence of saltpetermen in Thomas Middletons Jacobean play A Faire Quarrell. I am grateful to the editors of Past & Present for permission to incorporate material from my essay, Saltpetre, State Security, and Vexation in Early Modern England, published in Past & Present, no. 212, August 2011.

English weights made sixteen ounces a pound, fourteen pounds a stone, two stones a quarter, eight stones a hundredweight, and twenty hundredweight a 2,240 pound ton (1,016 kilograms). A thousandweight (abbreviated mwt) was ten times a hundredweight (cwt). Saltpeter and gunpowder were measured by hundredweights, thousandweights, and tons, and by barrels and lasts, a last comprising twenty-four barrels. Charcoal and coal were measured by the chalder (or cauldron) as well as by weight, a chalder of coal being 2,000 pounds before 1676 but 2,240 pounds (one ton) after revision.

Many of these measures varied by region, and different commodities had varying properties of weight and volume. Neither consistency nor precision should be expected. International merchants had to know that a Hamburg last was bigger than a last at Amsterdam, but smaller than a last in Prussia. A French livre was slightly heavier than an English pound. In England a hundredweight of saltpeter weighed 112 pounds, and a last of saltpeter 2,688 pounds (1.2 tons or 1,219 kilograms). Gunpowder, however, was measured differently. A hundredweight barrel of gunpowder weighed 100 pounds, and a twenty-four barrel last of gunpowder weighed 2,400 pounds (1.07 tons or 1,089 kilograms). The Dutch sold gunpowder and saltpeter by the quintal, which could vary from 100 to 120 pounds.1

Potential computational discrepancies arise with the variable formulae for gunpowder, and different ratings by hundredweights, barrels, and lasts for its constituent materials and final product. Unless otherwise indicated, I employ the standard mixture of 6:1:1, in which saltpeter is seventy-five per cent by weight of gunpowder, the rest being charcoal and sulphur. One pound of saltpeter therefore suffices to make 1.33 pounds of powder. Taking account of the differences in barrel-weight, one last of saltpeter would furnish 1.49 lasts of gunpowder. This calculation fits well with the estimate by Ordnance officials in 1588 that 112 thousandweight of saltpeter [i.e. 1,000 barrels or 41.66 lasts] will make sixty lasts of fine corn powder, whereby one last of saltpeter yields 1.44 lasts of gunpowder.2 Allowing for spoilage and spillage, waste, and further refinement, a working multiplier of 1.45 seems appropriate for gauging how many barrels or lasts of gunpowder can be supplied from given amounts of saltpeter.

The East India Company bought saltpeter in Asia by the maund and candy (twenty maunds), and had to know that a maund in Bengal weighed seventy-five pounds, whereas a Surat maund weighed twenty-eight pounds. The Company shipped saltpeter to London by the bag, each bag weighing on average about 1.2 hundredweight. Deliveries to the Ordnance Office were by numbered bags, converted by weight into tons, hundredweights, quarters, and pounds. Saltpeter contractors also took account of the refraction rate, around five or six pounds per hundredweight, lost in the conversion of gross or rough saltpeter to fine.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder»

Look at similar books to Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.