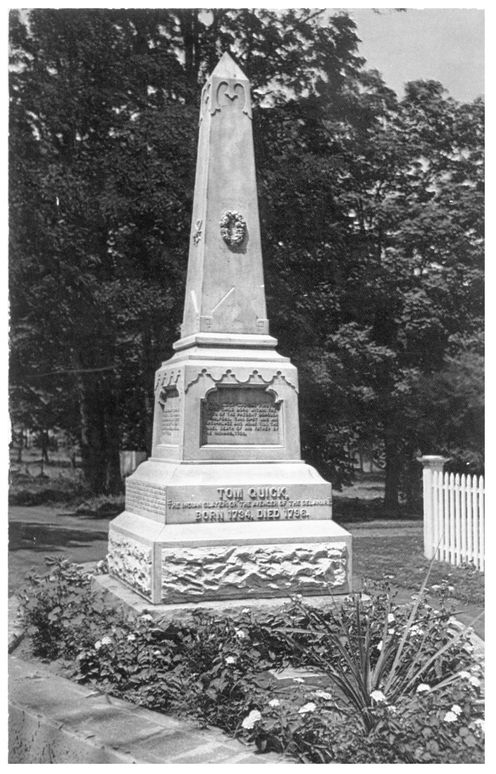

Tom Quicks Monument

F rom the Seven Years War through the American Revolution and until the Whiskey Rebellion, a frontiersman haunted the American imagination. Growing up on the Pennsylvania frontier as the eldest of ten, Tom Quick was one of those faceless, poorer men squatting or holding small tracts and struggling to achieve competency. Something, however, set him apart from

Quick killed Indians hunting, sleeping, eating, and drinking. He shot, tomahawked, stabbed, and bludgeoned Indians. He pushed Indians off of cliffs. He slaughtered them when sober and when drunk. He butchered men, women, and children, as well as whole families. As he put it after he had dashed out the brains of an infant, Nits make lice. He preyed on some close to his home, including the Delaware who had scalped his father, and ambushed others far away. During the American Revolution, heroamed frontier regions like the Ohio River valley in search of Indians but not as a patriot. Quick refused to join any militia. He would not support the British, either. Disaffected from any cause, he used the chaos of the period as a license to kill. Quicks reign of terror continued after the United States gained its independence as westerners still struggled with violence. Although proclaimed a monster by officials in these years, in the estimation of common settlers he seemed to stand alone against the indifference of government. In a world of all against all, in which civil society had ceased to exist, only he and his ilk could impose some sort of order. In particular, his unapologetic individualism appeared the only solution to incessant Indian raids. When authorities captured Quick, no jail could hold him because other frontier folks who had lost friends and relatives on the dark and bloody ground that the frontier had become came to his rescue.

Quicks spree ended in 1795. As legend had it, he had slaughtered ninety-nine Delawares when he fell ill withironicallysmallpox. As he lay dying, he pleaded with his family to drag one last Indian before the foot of his bed within rifle range. By 1795, however, few Indians lived on the Pennsylvania frontier. When Quick made his final request, some sense of order had come to the West as the violence and uncertainty that had gripped the region for decades had ended. So, too, had the presence of Indians in places like the Ohio valley. Quick died one Indian short of his grisly goal.

After Quicks death, his legend grew as westerners embellished stories of his vow, his guile, and the many Indians he had killed. The tale began to take even more extraordinary twists. One story that circulated transformed Quick into a deus ex machina, rescuing families under attack from Indians in the nick of time. In one such telling, he arrived breathless to confront and kill a few Indians besieging a house just as the father inside, low on ammunition, was preparing to sacrifice his own children and take his own life rather than see them suffer at the hands of savages. Another tale that made the rounds after he had died went something like this: After Quick was buried, a starving Indian came across the grave, dug up the body, and ate the liver. He then died of smallpox, a fitting end for the hundredth victim. Similar legends had whole villages wiped out by the diseased liver. In tales such as these, Quick achieved in death and a time of peace what he could not in life and a period of war.

By the early nineteenth century, easterners were reading romanticized accounts of stories like the Quick myth as books and pamphlets appeared cataloging the exploits of frontiersmen. In these years, the ideas of century, in other words, the history of what had been one of Tom Quicks hunting grounds for many defined the character of American character.

With time, Americans elevated the likes of Tom Quick to sacrosanct status. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Quick tall tale had been rediscovered and had become the subject of popular books and even a play titled Tom Quick, the Avenger; or, One Hundred for One. Its author claimed Quick took his vow to defend the defenseless and out of regard for the memory of a father savagely executed:

By the point of the knife in my right,

and the deadly bullet in my left;

By heaven and all there is in it,

by earth and all there is on it;

By the love I bore my father,

here on his grave I swear eternal vengeance

against the whole Indian race.

I swear to kill all, to spare none;

The old man with the silver hair,

The lisping babe without teeth,

the mother quick with child, and

the maid in the bloom of youth shall die.

A voice from my fathers grave cries

Revenge! Eternal revenge!

According to another account, Quick was the very ideal of strength, tall, powerful, agile, and bright, an individual untethered from society. Quick epitomized the triumph of civilization and democratic values over savagery. Although he had sacrificed innocents, he did so in the service of a broader white civilization. He was its leading edge, societys unrefined precursor and necessary evil.

Late-nineteenth-century Pennsylvanians were not alone in finding meaning in men like Quick. The historians and cultural icons George Bancroft and Frederick Jackson Turner, who were writing as frontier legend captured the attention of Americans, also believed that the American Revolution fulfilled a destiny and that the frontier created a distinctive people, uncontaminated by the trappings of hereditary power, relentless class conflict, and vexing ethnic questions that dogged the Old World. Ifthe Revolution signaled the arrival of a distinctively conceived nation, the frontier provided the requisite labor. As Turner explained, on this unforgiving line between savagery and civility, men and women developed those traits most closely associated with Americanness. They did so by taming a place and conquering the savage peoples who inhabited it. Better considered a process than a place, the frontier taught settlers the lessons of democracy. Here, out of necessity, they discovered the virtues of self-reliance and freedom from the dictates of government. Fighting Indians and scrambling to survive, in other words, created the conditions for the triumph of popular political participation. The Revolution as event and the frontier as process therefore confirmed America as the exceptional nation that many a century agothen flush with hope about the place of the United States in the wider world but wary of growing tensions at homeassumed that it was.

The legends of men like Quick became the stuff of American myth. By taming a frontier, settlers like him had transformed the way society functioned in the West and, as Turner suggested, in the larger nation as well. No one can read their petitions, Turner wrote, denouncing