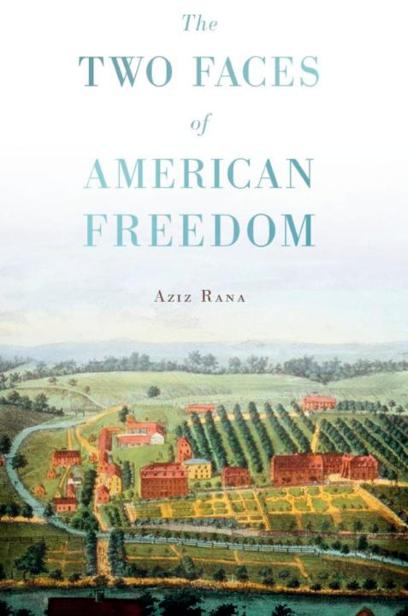

Aziz Rana

For my parents and Odette

Long having wander'd since, round the earth having wander'd, Now I face home again, very pleas'd and joyous, (But where is what I started for so long ago? And why is it yet unfound?)

-Walt Whitman, "Facing West from California's Shores" (1860)

It is not surprising for members of a political community to follow their domestic elections closely or to celebrate the victory of favored candidates. It is surprising, however, when individuals do the same for a political contest taking place in a distant country, to which they have little apparent relationship and in which they have no capacity to influence the outcome. Yet, in the days before and after Barack Obama's election as president of the United States, not only did individuals throughout the world pay rapt attention to the results, many engaged in spontaneous celebrations. Few of those who took part in such political fanfare were U.S. citizens. In places like Kenya and Indonesia, most had never visited the United States (nor were they ever likely to), and at no point during the election had their daily concerns surfaced as part of the political discussion.

This global attention suggests two remarkable features about how America finds itself currently embedded in the international order. First, Obama's victory highlighted the continuing power of the American example. In recent years, national prestige has been badly tarnished by the global unpopularity of foreign wars as well as by the much-publicized human rights violations of detainees. But, for communities across the globe, the fact that a multiracial man of middle-class background could reach the presidency spoke to another vision of the country. It emphasized the vitality of the American dream-the notion that in the United States everyone has the opportunity to achieve economic success, social respectability, and political office. To the extent that American commentators focused on the international response at all, this was their primary interpretation: the outpouring of affection illustrated the United States' undiminished standing as the "first nation" among equals and as a symbol of liberty.

At the same time, the world's interest in the election dramatized a second, less explored feature. The United States today enjoys tremendous and perhaps historically unparalleled economic, military, and political power. In the wake of the recent financial crisis, some domestic commentators have questioned whether the country is losing this international preeminence, especially to emerging states such as China.' Yet, despite the fear of decline, by most barometers America's position as sole global superpower remains firm. Its output amounts to 20 percent of the world's total and nearly doubles that of China, the next closest country.2 In terms of sheer military might, the United States accounts for almost half of global defense expenditures, a number equal to the following twenty nations combined.' As of 2009, some 516,273 military service membersnot including Department of Defense civilian officials-were deployed abroad, stationed across 716 reported overseas bases and present in approximately 150 foreign states (nearly 80 percent of the world's coun- tries).4 The United States employs this authority directly and indirectly to shape international institutions, to intervene in the domestic politics of foreign countries, and to enlist weaker nations to implement American goals. Perhaps more than anything else, the world's fixation with the U.S. presidential election spoke to this reality. Scenes of rapt attention and celebration thus presented a vision of those at the very edges of American power looking to the center to see what the future might hold. It also suggested a startling disjunction: while American citizens were largely unaware of these groups or of how U.S. influence affects them, those at the periphery by contrast felt bound to the country and its practices.

This book is an effort to make sense of the transformations in the relationship between American liberty and American power. The present moment is hardly the first time that the United States finds itself exercising authority over communities that are not considered properly American. In fact, the American Revolution itself was centrally concerned with basic disagreements between colonists and British administrators regarding the meaning of political membership as well as how governments may appropriately assert power over both insiders and outsiders. In the following pages, I engage in a large-scale act of historical reconstruction that begins with the national founding and explores the degree to which American projections of power have become unmoored from clear democratic ideals. In the process, I reinterpret the lasting implications of our political origins and shed light on how questions of settler identity, economic independence, and ethnic assimilation grounded popular contests regarding social inclusion and the substantive meaning of freedom. In particular, I argue that most of the American experience is best understood as a constitutional and political experiment in what I term settler empire and that we cannot understand how accounts of expansion, immigration, race, and class have been intertwined at various historical moments without appreciating the larger ideological and institutional context.