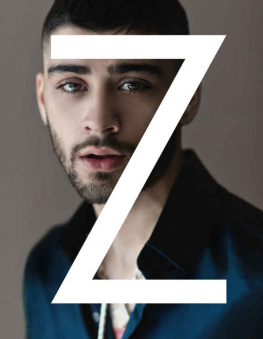

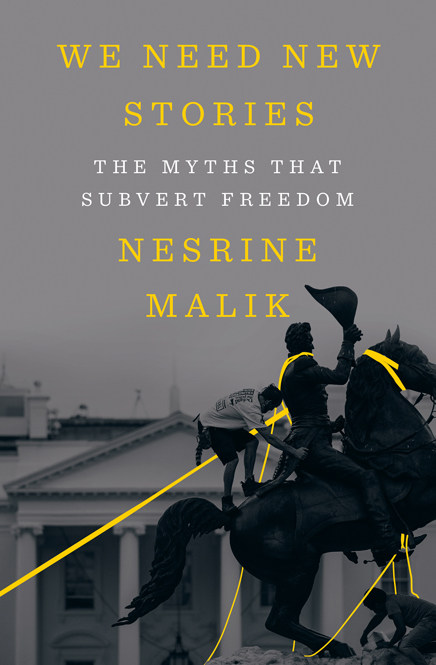

Nesrine Malik - We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom

Here you can read online Nesrine Malik - We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: W. W. Norton & Company, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom

- Author:

- Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nesrine Malik: author's other books

Who wrote We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

WE NEED

NEW STORIES

The Myths That

Subvert Freedom

Nesrine Malik

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

Im sure you believe everything youre saying. But what Im saying is that if you believed something different, you wouldnt be sitting where youre sitting.

Noam Chomsky, to BBC interviewer

O n the day of the 2016 American presidential election, I called a New Yorkbased journalist who was covering the campaign and caught him just as he was about to walk out of his apartment and onto the streets of the city to soak up the atmosphere.

Trump is going to get his ass kicked, he said, and I wanna be there to see it. I laughed, told him I was jealous, then went to bed.

When I woke up only a few hours later it was still the middle of the night in London, but it looked very much like Donald Trump was not in any way getting his ass kicked. I called the journalist again.

Its not looking good, he said. Im sure I heard his voice catch.

What followed was a media-wide crisis of confidence, one that roiled the liberal establishment in general. The polls, the reporters on the ground, the holy goddamn New York Times swingometer all reflected the consensus opinion that Trump was, as my journalist friend had said, going to get his ass kicked. Later the next day, I sat with some other journalists in a London pub. It was a fractious evening. An argument about Hillary Clinton as a flawed candidate broke out. In another tense exchange someone objected to the statement that Trump had a good instinct. What was really going on among this group of friends and colleagues was that no one knew what was going on.

An almost identical scenario had unfolded a few months earlier. On the night of the EU referendum in the UK, I went to bed after hearing Nigel Farage, the face of the Leave EU campaign, make a pre-concession speech. I woke up to a country that had voted to leave the EU. I plugged news radio into my ears as I left for work because it was all happening so fast. David Cameron resigned as prime minister before I had even caught the bus.

Later that day, the media machine swirled in a vortexreporters hustled to set up interviews to meet the spike in demand and editors readied new front pages as the industry tried to adjust to the wavelength that it had not picked up. For a few days, it seemed implausible that no one at the top had resigned for their failure to see the change coming. As a columnist, I felt it was surreal to make do with explainers for what happened when I had not written a single piece predicting the outcome. It was the media equivalent of working at a bank on a day the financial market crashed and stock prices went to zero. The industry was caught packaging ideas and repackaging them to the extent that they became completely disconnected from any authentic reporting. This was our own version of subprime mortgages. When the real world came knocking, the ideas were worthless, and no one knew or remembered how the process had worked in the first place. An editor in the US told me that the atmosphere in his newsroom felt as if there had been an assassination. The same applied to my British colleagues. The mood was funereal. How could we carry on as normal? What was the media for? Two paths could be taken at this momenteither we could reckon with all the ways the media is not separate from power in the representative makeup of its body and its independence of thought, or we could deny that there was a problem.

We took the denial route. There was no wholesale appraisal of our failure to report and explain the facts, as opposed to echoing back industry and political class conventional wisdom. Whenever the media fails epically on a moral or reporting scale, whether it is the Iraq War or the failure to take Donald Trump seriously, a few mea culpas are issued but, all in all, nothing changes. This is the norm. Plagiarism and falsification are red lines, but gullibility and lapses in moral judgment are par for the course. If a politician is disgraced, she resigns. If a fund manager loses money, she loses her job. But in journalism there is an impunity of tenure. The fact that we did not see it coming meant not that there needed to be serious introspection, but that no one could have possibly seen it coming. We were reliable narrators.

I start with this myththe myth of the reliable narratorbecause it underpins all the rest. Unreliable narrators from academia, the publishing world, and from the journalism industry have been a roadblock to addressing structural inequality. They are the main conduits for communicating all the other myths that prop up the establishment and defend it against movements for change. We believe in their neutrality and thus do not question the accounts of the world which they have recounted to us. These unreliable narrators present themselves as free of bias, of identity, of politics. Their moral and political miscalculations are not benign oversights or human errorthey are harmful lies. Unreliable narrators dictate the popular accounts of mainstream history, how we talk about identity politics, and they give intellectual cover to our politicians. The role such narrators play in stemming the tide of change is paramount. We need new narrators to clear the path for change.

Narrators of myths use tools, a set of argumentative techniques that are tailored for each myth. Whenever marginalized groups ask for meaningful social transformation, these narrators wield specific tools to divert attention from grievances and discredit movements for equality.

Our allegedly reliable narrators deploy these tools by leveling certain lines of criticism at their targets. These movements are too woke, too politically correct, too radical, too taken with identity politics, too eager to shut down free speech, too vindictive to respect due process, too righteous, too thin-skinned. Closely aligned with power, these narrators make dire moral judgments for which they are rarely punished.

The Iraq War remains a helpful illustration of this coziness with political authority. While some of those politicians who launched and supported military intervention have faced questions about their decisions to go to war, the ecosystem that forced through their warmongering has not come under any scrutiny despite admissions that mistakes were made.

In 2004, the New York Times issued a mea culpa, stating that the editors had found a number of instances of coverage that was not as rigorous as it should have been. They said: In some cases, information that was controversial then, and seems questionable now, was insufficiently qualified or allowed to stand unchallenged. Looking back, we wish we had been more aggressive in re-examining the claims as new evidence emergedor failed to emerge. The main problem was that accounts of Iraqi defectors were regurgitated by government officials, the neutrality of which the New York Times simply assumed. Consequently, they reprinted officials claims about weapons of mass destruction without sufficient question.

In the same year, the Washington Post issued a similar apology in a three-thousand-word front-page article. The newspaper said that it did not pay enough attention to voices raising questions about the war. Leonard Downie Jr., the Posts executive editor, said: We were so focused on trying to figure out what the administration was doing that we were not giving the same play to people who said it wouldnt be a good idea to go to war.... Not enough of those stories were put on the front page. That was a mistake on my part.... The voices raising questions about the war were the lonely ones. We didnt pay enough attention to the minority.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom»

Look at similar books to We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book We Need New Stories: The Myths that Subvert Freedom and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.