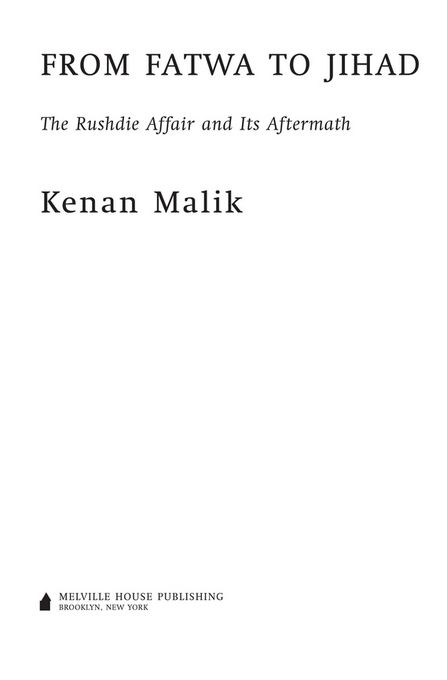

Kenan Malik - From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath

Here you can read online Kenan Malik - From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Melville House, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath

- Author:

- Publisher:Melville House

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Kenan Malik: author's other books

Who wrote From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FROM FATWA TO JIHAD

First published in hardcover in Great Britain in 2009

by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright Kenan Malik, 2009

All rights reserved

First Melville House Printing: June 2010

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

mhpbooks.com

eISBN: 978-1-935554-75-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010923402

v3.1

For Carmen

(who seems to have little trouble with

the concept of free expression)

How Salman Rushdie Changed My Life

How Salman Rushdie

changed my life

A poets work, he answers. To name the unnamable, to point at frauds, to take sides, start arguments, shape the world and stop it from going to sleep. And if rivers of blood flow from the cuts his verses inflict, then they will nourish him.

Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses, p.97.

It was February 1989. I was in Bradford, a grey town in northern England. Nestled in the hills of West Yorkshire, it was a place dominated by its woollen mills, huge Victorian structures that seemed to reach up into the clouds, though by the late eighties few were still producing any wool. Surrounding the now derelict mills were row upon row of dreary back-to-back houses that had become as decayed as the textile industry itself. The mood of the town was not improved by a climate grey like its brickwork.

It was a town of which few people outside of Britain would have heard. Until, that is, a thousand Muslim protestors had, the previous month, paraded with a copy of Salman Rushdies The Satanic Verses, before ceremoniously burning the book. The novel was tied to a stake before being set alight in front of the police station. It was an act calculated to shock and offend. It did more than that. The burning book became an icon of the rage of Islam. Sent around the world by a multitude of photographers and TV cameras, the image proclaimed, I am a portent of a new kind of conflict and of a new kind of world.

Ten months after that January demonstration an even more arresting image captured the worlds imagination: protestors on top of the Berlin Wall hacking away at their imprisonment. These two images the burning book in Bradford, the crumbling wall in Berlin came in the following years to be inextricably linked in many peoples minds. As the Cold War ended, so the clash of ideologies that had defined the world since the Second World War seemed to give way to what the American political scientist Samuel Huntington would later make famous as the clash of civilizations (a phrase he had borrowed from the historian Bernard Lewis). The conflicts that had convulsed Europe over the past centuries, Huntington wrote, from the wars of religion between Protestants and Catholics to the Cold War, were all conflicts within Western civilization. The battle lines of the future would be between civilizations. Huntington identified a number of civilizations, including Confucian, Japanese, Hindu, Orthodox, Latin American and African. The primary struggle, however, would be, he believed, between the Christian West and the Islamic East. Such a struggle would be far more fundamental than any war unleashed by differences among political ideologies and political regimes. The people of different civilizations have different views on the relations between God and man, the individual and the group, the citizen and the state, parents and children, husband and wife, as well as differing views of the relative importance of rights and responsibilities, liberty and authority, equality and hierarchy.

Huntington did not write those words until 1993. But already, four years earlier, many had seen in the battle over The Satanic Verses just such a civilizational struggle. On one side of the fault line stood the West, with its liberal democratic traditions, a scientific worldview and a secular, rationalist culture drawn from the Enlightenment; on the other was Islam, rooted in a pre-medieval theology, with its seeming disrespect for democracy, disdain for scientific rationalism and deeply illiberal attitudes on everything from crime to womens rights. All over again, the novelist Martin Amis would later write, the West confronts an irrationalist, agonistic, theocratic/ideocratic system which is essentially and unappeasably opposed to its existence. Amis wrote that while still in shock over 9/11. The germ of the sentiment was planted much earlier, in the Rushdie affair.

Shocked by the sight of British Muslims threatening a British author and publicly burning his book, many people started asking a question that in 1989 was startlingly new: are Islamic values compatible with those of a modern, Western, liberal democracy? The Bible, the novelist, feminist and secularist Fay Weldon wrote in her pamphlet Sacred Cows, provides food for thought out of which You can build a decent society. The Quran offers food for no thought. It is not a poem on which a society can be safely or sensibly based. It forbids change, interpretation, self-knowledge, even art, for fear of treading on Allahs creative toes. Or as the daytime TV chat-show host and one-time Labour MP Robert Kilroy-Silk put it, If Britains resident ayatollahs cannot accept British values and laws then there is no reason at all why the British should feel any need, still less compulsion, to accommodate theirs.

Even those who had originally welcomed Muslims into Britain were having second thoughts. As one of Britains most liberal Home Secretaries, Roy Jenkins had, in 1966, announced an end to this countrys policy of assimilation and launched instead a new era of cultural diversity, coupled with equal opportunity in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance one of the first expressions of what came to be known as multiculturalism. Nearly a quarter of a century later, the now ennobled Lord Jenkins mused in the wake of the burning book that in retrospect we might have been more cautious about allowing the creation in the 1950s of substantial Muslim communities here.

I had watched the burning of The Satanic Verses with more than a passing interest. Like Salman Rushdie, I was born in India, in Secunderabad, not far from Rushdies own birthplace of Mumbai (or Bombay, as it was then), but brought up in Britain. Like Rushdie, I was of a generation that did not think of itself as Muslim or Hindu or Sikh, or even as Asian, but rather as black. Black was for us not an ethnic label but a political badge (although we never defined who exactly could wear that badge). Unlike our parents generation, who had largely put up with discrimination, we were fierce in our opposition to racism. But we were equally hostile to the traditions that often marked immigrant communities, especially religious ones. Today, when people use the word radical in an Islamic context, they usually have in mind a religious fundamentalist. Twenty years ago radical meant the very opposite: someone who was militantly secular, self-consciously Western and avowedly left-wing. Someone like me.

I had grown up in communities in which Islam, while deeply embedded, was never all-consuming indeed, communities that had never thought of themselves as Muslim, and for which religion expressed a relationship with God, not a sacrosanct public identity. Officially, as it were, observes Jamal Khan, the narrator of Hanif Kureishis novel Something to Tell You, we were called immigrants, I think. Later for political reasons we were blacks In Britain we were still called Asians, though were no more Asian than the English are European. It was a long time before we became known as Muslims, a new imprimatur, and then for political reasons. So what, I wanted to know, as I watched the pictures of that demonstration, had changed? Why, I wondered, were people now proclaiming themselves to be Muslims and taking to the streets to burn books especially the books of a writer celebrated for giving voice to the migrant experience? And was the dividing line really between a medieval theology and a modern Western society?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath»

Look at similar books to From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.