A matter of weeks

rather than months

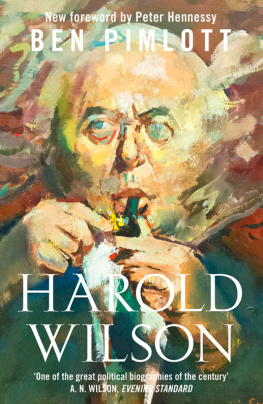

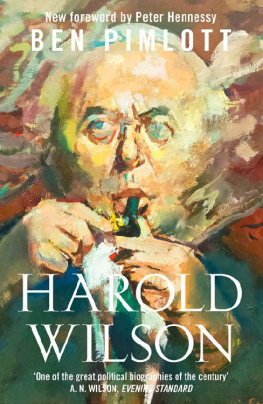

The Impasse between Harold Wilson and Ian Smith

Sanctions, Aborted Settlements and War 1965-1969

J.R.T.Wood

Order this book online at www.trafford.com

or email orders@trafford.com

Most Trafford titles are also available at major online book retailers.

Copyright 2012 J.R.T.Wood.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

ISBN: 978-1-4669-3409-2 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-4669-3410-8 (e)

Trafford rev. 08/21/2012

www. trafford.com

www. trafford.com

North America & international

toll-free: 1 888 232 4444 (USA & Canada)

phone: 250 383 6864 fax: 812 355 4082

Dedication

to

AMP CAW & ATW

MR

PMB & TJB

CJSW & EMGW

CDM & JM

All of whom have continued to inspire and help me selflessly.

Contents

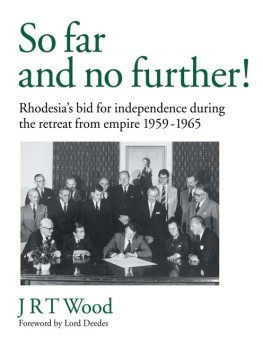

Following my two published works on post-Second World War Rhodesian history, The Welensky Papers: A History of the Federation of Rhodesia andNyasaland: 1953-1963 and So Far and No Further! Rhodesias bid for independence during the retreat from empire: 1959-1965, this book is the third fruit of my 37 years of research.

As in So Far, this book concentrates on the Anglo-Rhodesian political and constitutional wrangle over independence in the immediate post-UDI period, culminating in Ian Smiths declaration of a republic. It describes also the first phase of the ultimately successful African nationalist armed bid for power. This bid was fuelled by the Cold War sponsorship of national liberation struggles. The after effects of this are still being felt in Africa as a consequence of the flooding of the continent with AK-47 assault rifles and similar weapons. Training was also supplied for young African recruits sent abroad to Soviet and Chinese Communist guerrilla warfare schools and to similar establishments in their satellite and allied countries. What the Zimbabwe African National Union and its rival, the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union, and the latters ally, the African National Congress of South Africa, lacked in this period was sufficient popular support. Their leaders, however, misunderstood this and sent young men across the Zambezi River into Rhodesia to spark an uprising. There they rarely avoided arrest or death, many of them being captured by the rural African people and handed over to the security forces. Although this could be interpreted as evidence of support for the Rhodesian Government, it is more likely a reflection of the universal conservatism of the subsistence farmer who has everything to lose if current order is disturbed. It was also a rejection of the violent intimidation which characterised the African nationalist pre-UDI and post-UDI campaigns. Whatever the politicians on both sides might have said or pretended, the African population remained largely neutral, biding their time for better days. Admittedly, Africans served loyally and fiercely in the British South Africa Police and the armed forces but then, universally, soldiers fight for the men on either side of them and for their unit.

If this initial success did not mislead the Rhodesian military hierarchy about the threat posed by the African nationalist insurgency, it did their political masters. It led them to disregard it and to concentrate on the immediate problem of resolving the political and constitutional impasse. There was, however, no political solution which would be acceptable either to the British Labour Government of Harold Wilson, still smarting over Ian Smiths rebellions, or the defiant Rhodesian Front one of Ian Smith. It meant that, not only was Rhodesia hobbled by sanctions but it was denied any form of legitimacy while Britain refused to transfer sovereignty. Without sovereignty, Rhodesia was denied access to international support, capital and more. The reality remained that no British government during post-Second World War retreat from empire could grant independence on the basis of the denial of majority African rule. Despite being committed to political evolution, the Rhodesian whites knew, however, that an early transfer of power to the African elite spelled the end of their control of all of the modern state they had built in 70 years in the heart of Africa. They knew that it was political suicide. The British on the other side of the negotiating table, constrained by domestic, Commonwealth and international realities, could offer only the minimum reprieve. This was a period of impotent frustration on all sides.

My detailed reconstruction of the events of 1965-1969 is again based on my access to the Papers of Ian Smith, housed in the Cory Library, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. I have used the collections in the Library of Rhodes House, Oxford, and The National Archives at Kew, London. [I am among the many lovers of tradition who deplore the dropping of the name, Public Record Office, by the modernising New Labour administration. Every country has a national archives. Only Britain had the PRO.] I have also had the fortune to be trusted with access to the hitherto secret archives of the Rhodesia Army Association now housed in the British and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol, England.

I have continued to be assisted and sustained by the generosity of others. The same generous friend who rescued my project in 1999 has funded my research and the long days of writing. The Hon. Ian Douglas Smith has also assisted with access to his papers with unstinting willingness to answer questions. Colonel John Redfern and members of the Flame Lily Foundation have also assisted with advancement on sales and access to information. Colleagues with similar interests, notably Major Charles David Melson, the Chief Historian of the United States Marine Corps has helped in innumerable ways including providing a constant stream of photo-copied material of his own research into the Rhodesian counter-insurgency effort. In this, he was aided by the author, Alexandre Binda of the new regimental histories, The Saints: The Rhodesian Light Infantry and Masoja: The History ofthe Rhodesian African Rifles, who has sent to both of us the documents underpinning his research. My sister, Patricia, and her husband, Tim Broderick, in Harare, Zimbabwe, have continued to pass on documents, cuttings, messages and securing interviews. My work was founded on the enduring generosity of others who made trips to libraries and archives abroad possible. I still owe debts of gratitude to Christopher and Geraldine Woodwark, Michael and Karen Woodwark, Charles and Janet Melson, Michael and Ann Noone, Craig and Diohn Benedict, Ivor and Sally Ingall, Rowena and Bill Quantrill, my late cousin, David Arnold and his wife, Patricia, and Brigadier David Heppenstall and his wife, Ann. James Porter assisted with access to computers. Professor Michael Laidlaw and Genevieve Hadlow have repaired and maintained my computers and solved many problems. Professor Irina Filatova and Bill Johnson have supported me. John Devereux, a man of great talent and patience, is responsible for laying out the book and designing the cover. Dr James Hargrave, the archivist of the Welensky Papers, has never failed to offer advice and assistance. Selvie Pillay has attempted to make me appear tidy. My son, Andrew, has cheerfully endured the disruption of my visits to his house in London and has patiently answered questions on the mysteries of the computer and has sourced and secured equipment and the like.

Next page

www. trafford.com

www. trafford.com