WESTERN IMAGININGS

WESTERN IMAGININGS

The Intellectual Contest to Define

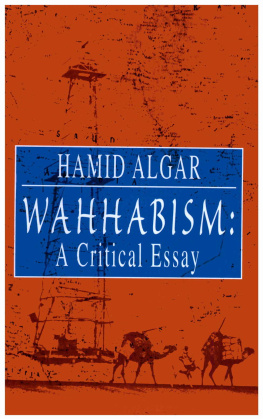

Wahhabism

ROHAN DAVIS

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

Copyright 2018 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 977 416 864 2

eISBN: 978 161 797 876 0

Version 1

For my parents, Janice and Phil

And thank you Rob, Im eternally grateful

Contents

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T.S. Eliot, The Four Quartets

Like so many other authors, my researching and writing this book was inspired and motivated by an experience that had a profound effect on me. In 2008 I was in Stockholm, Sweden, staying in a small student apartment in the south of the city. It soon became clear to me that if I wanted to have something close to an authentic Swedish experience, then I needed to speak and understand some of the Swedish language. So I enrolled in a beginner-level Swedish language course, two classes a week. The classes had few students, and they were relaxed and enjoyable. The most interesting aspect of this experience was the friendships I made with other students while talking during coffee breaks and after class. It was a chance encounter with one young man in particular that would forever change how I would understand the world and which would inspire the years of researching and writing this book.

My new friend was from Palestine. We got to know each other during lunch and coffee breaks, and each week we shared more about life in our home countries. His story was particularly interesting because it gave me an insight into what it was like for Palestinians living under Israeli occupation. He told me about how the Israel Defense Forces had forcibly removed him and his family from their homes, and with no place to live, they fled to a Jordanian refugee camp. He lived in the camp for a few years until his application for asylum was eventually accepted by the Swedish government.

With the help of the Swedish refugee services, he was resettled in Kiruna, one of Swedens most northern, darkest, and coldest cities. The small city is located north of the Arctic Circle, meaning it experiences both the midnight sun and the polar night throughout the year. Even for Swedes, Kiruna is especially cold, and it could not be any more different to the parched Palestinian landscape. Following the end of his employment in a factory, my new friend moved to suburban Stockholm where he lived with three other Middle Eastern refugees. Unable to speak Swedish fluently, he wanted to both communicate with the people of his adopted nation and have better employment opportunities. This inspired him to join the Swedish language class.

Up until this point in time I had never shown great interest in the situation in Palestine. When I thought about the ongoing conflict, far away from the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia, where I grew up, all I could recount was the narrative that tended to dominate the Western media: the Palestinians were by and large terrorists whose desire to violently attack Israelis was in part motivated by their radical Islamic beliefs. While we hear a lot more stories now about the dire situation in places like the West Bank and Gaza, my thoughts about the ongoing conflict were dominated by media reports about what they referred to as pro-Palestinian terrorist groups.

This narrative was however completely contradicted by what my new Palestinian friend was telling me. He was neither a terrorist nor a hater of Jews. He abhorred violence and did not want retribution against those responsible for displacing him, his family, his friends, and neighbors from their land. He wanted to spend his time doing what he lovedplaying soccer, drinking coffee, and smoking. He called smoking his dirty habit, which he began during his time in the refugee camp to help him relieve stress, suppress his hunger, and pass the time. Like most people he also dreamed of falling in love and having a family. Most importantly, my conversations with him revealed to me another viewpoint about the ongoing IsraeliPalestinian conflict.

The stories I was told by the mass media about the conflict simply did not match up with what this man was describing, so I went online, searching for alternative news sites. The more I read, the more I became aware of the many competing narratives and categories writers were using when representing the alleged terrorist threat posed by Palestinians. One of the categories used by some writers that piqued my interest was something they were calling Wahhabism.

More research helped reveal to me that this was a term that became increasingly popular among Western scholars and commentators following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. Prior to these attacks few Western scholars and commentators wrote about this phenomenon, and of those who did it was usually in relation to the role it played in the forming of the modern Saudi state. Articles about Wahhabism rarely appeared in popular US newspapers and magazines, and it was largely ignored by the plethora of US-based think tanks and foreign policy organizations now churning out documents about this primarily religious phenomenon. The 9/11 terrorist attacks were a turning point, as commentators began using the term when describing the influence it supposedly had on the Saudi Arabian hijackers. Furthermore, Western scholars and commentators began linking this Saudi state-sanctioned religion to Islamic radicalism and violent extremism throughout the world. The more reading I did, the less convinced I was of the apparent relationship between Wahhabism and Palestinian violence, which many US-based right-wing, conservative, and pro-Israeli commentators were claiming. My Palestinian friend had certainly never used the term. That experience planted a seed that has since grown to become this book.

This book is my modest attempt at understanding how the phenomenon Wahhabism has been represented by authors writing in a post9/11 world characterized by anxiety about terrorism between and inside states. I am particularly concerned with how intellectuals belonging to the liberal and neoconservative traditions represent Wahhabism, and the different truth claims they rely on to support these representations. This book is also designed to understand some of the ways in which different ethical, political, and religious motivations are informing these representations.

I have set out a number of questions to help focus my book. They are: How have scholars represented Wahhabism? What kinds of problems are there with these interpretative exercises? What kinds of problems can we find in the sociology of intellectuals that warrant this kind of enquiry? How do liberal and neoconservative intellectuals in particular represent Wahhabism? And how are we to understand and make sense of these representations?

At this point it is important to briefly set out why I am focusing on representations of Wahhabism and not what is referred to as Wahhabism. There are numerous considerations that are shaping my inquiry. Though this proposition needs and gets some more elaboration later in the book, I want to highlight the basic difficulty of engaging with Wahhabism itself. There are good grounds for doubting that the phenomenon of Wahhabism has some natural or objective reality that can be immediately grasped as if it were a physical object. While we cannot see, feel, or touch the different social and intellectual processes constituting Wahhabism, we can examine its various representations. Additionally, it is hard to study a phenomenon in the social world for which we do not have a standard or widely agreed upon conceptualization or definition. Wahhabism, as I explain, is a contested category.