Cherian George and Donald Low, 2020

18

Riding the populist tiger

Reactionary populism may offer tempting political advantages, but only at the cost of the PAPs technocratic strengths and Singapores cherished pluralism.

Lee Kuan Yew and his PAP Old Guard peers came to power through a cunning alliance with militant leftist leaders and activists brimming with street cred and accomplished at mobilising the masses. Lee and his faction were savvy enough to understand their own limitations and harness the power of others and then to jump off before being consumed by them. They called the high-risk gambit riding the tiger.

The 1990s brought a very different beast to mount. Lee, always ill at ease with the commercial world, decided that the government had to work with local businesses and street-smart entrepreneurs, if the Singapore economy was to benefit from growth in the region and beyond. Meanwhile, reflecting the neoliberal ideology sweeping across the world, many government activities were privatised (think telecommunications, electricity generation, even public hospitals and some parts of public housing). The public sector was encouraged to adopt commercial best practices. Citizens would be called customers. Most controversially, Ministers pay was benchmarked to that of top earners in the private sector. The challenge was, again, how to internalise powerful and potentially untameable forces without being overwhelmed by them.

Over the past decade, the PAP government has felt compelled to make another Faustian pact. As in previous instances, the party has been seduced by the promise of overcoming its limitations. This time, the force that has seized its imagination is not the mobilising energy of communism nor the market impulse of commerce, but the defensive potential of reactionary populism. Like previous tigers, this phenomenon emerged from the wild: not the literal jungles where communists mounted their anti-Japanese and then anti-British guerrilla wars, nor the amoral habitats of economic markets, but freewheeling cyberspace, where anti-PAP elements had run riot for more than a decade. If you cant beat them, the saying goes, then join them. Thus it came to pass that populist methods and tropes associated with insurgent anti-establishment groups have been borrowed by the ruling party.

This has happened gradually, alongside society-wide and global cultural shifts. This is probably why many observers and insiders do not consider the change remarkable. Indeed, most younger Singaporeans probably consider these traits to be as normal and natural as walking around with a high-performance computing and video-communication device in their hands, even though smartphones have ushered in ways to interact and organise that would have been unrecognisable, even bizarre, just 20 years ago.

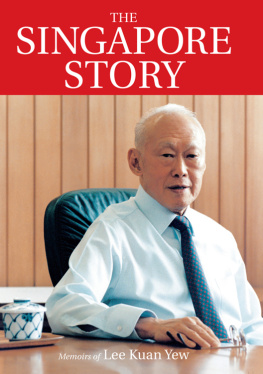

In an age of Facebook posts and Instagram influencers, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that Lee Kuan Yews PAP wasnt just less populist, it was actively anti-populist. Most Singaporeans probably welcome the change. Lees top-down lecturing style may have suited his times, but most now expect leaders to be more approachable. They also want elected representatives to be more reflective of popular will. But the shift in communication style or electoral representation isnt what concerns us here. It is something more fundamental: the role that popular sentiment should play in policy-making, the rule of law, human rights and the social compact.

The popular will, expertise and individual rights

Populism, popular, public, people. These are potentially confusing terms. Their ambiguity is exploited by demagogues around the world. It can also confound a PAP trying to find the right formula for accountable and responsive leadership. So its important to understand how these terms relate to the principle of democratic government. At one level, of course, democracy is about government of, for and by the people, a system for ensuring that collective decisions are guided by the popular will.