Acknowledgments

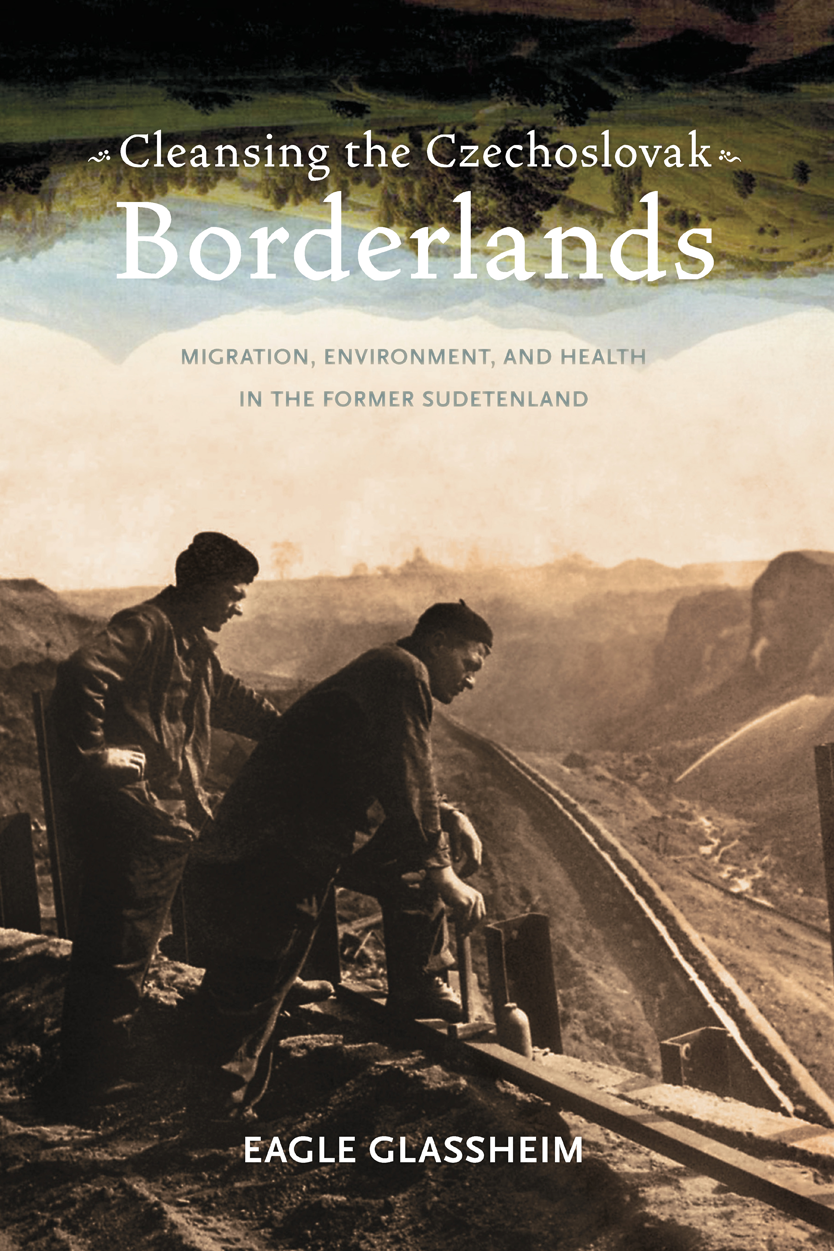

I have always been fascinated by alleys: receptacles for our waste, abandoned furniture, wires, and other things we often prefer to tuck out of sight. Rather than squalor, I see authenticity; rather than aesthetic wasteland, I see the necessary underpinnings and sometimes unhappy reality of our lives as they are. Front yards are for show. For these insights and metaphors, and many of the questions that animate this book, I thank my parents, Eliot Glassheim and Patricia Sanborn. They have guided me, in poetry and in prose, through half a lifetime of productive unease.

My research on the Czechoslovak borderlands began in 1997, when Benjamin Frommer recruited me to present a paper at a multinational, multilingual forced-migration conference in Gliwice, Poland. Special thanks to Ben, and to conference organizer Philipp Ther, for their collegiality and friendship then and since.

Many other colleagues and friends have given me ideas, feedback, and encouragement as I continued to work on this project in fits and starts since the late 1990s. Among others, I want to thank Chad Bryant, Andrew Demshuk, Andrew Denning, Pieter Judson, Padraic Kenney, Jeremy King, Norman Naimark, Clara Oberle, Stanislav Pejsa, Vanda Skalov, Matj Spurn, Jindich Toman, David Tompkins, Nancy Wingfield, and Tara Zahra. And warm regards to members of the Kennebunkport Circle, who read the entire manuscript and were helpfully skeptical of my Heimat musings at crucial moments in the project: Melissa Feinberg, David Frey, Paul Hanebrink, and Cynthia Paces. Any remaining sentimentalism is the responsibility of the author alone.

I researched and wrote much of this book at Princeton (20002005) and the University of British Columbia (2005present). Both have been collegial and generous places to work, providing me the time, financial support, and networks of colleagues so crucial to what became a very long-term project. Though I benefited from the suggestions of dozens of colleagues, I want to thank in particular Stephen Kotkin, AnthonyGrafton, and Molly Greene at Princeton; and Courtney Booker, Robert Brain, Matthew Evenden, Chris Friedrichs, Anne Gorsuch, Tina Loo, Leslie Paris, Coll Thrush, and Jessica Wang at UBC. I am also grateful for help and thoughtful feedback from UBC graduate students, including Kelly Cairns, Ken Corbett, Jan-Henrik Friedrichs, Alexey Golubev, Stefanie Ickert, Birga Meyer, and Baris Yorumez.

I am also grateful for grants that have allowed me to complete my research and writing. The Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and Woodrow Wilson Center supported a year of intensive research early in the project. Canadas Social Science and Humanities Research Council sustained the project through its extended middle (corresponding to the birth of my two daughters, as well as a few chapters). And the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society gave me (and my entire family) a congenial home and support in Munich as I was finishing up, or at least trying to finish up. Thanks especially to Carson Center directors Christof Mauch and Helmut Trischler, and to my fellow fellows in 2012, for sharing a wealth of good ideas and good company.

Many thanks to archivists in northern Bohemia, who welcomed me and my dog Coqui on several productive and enjoyable research visits: Helena Smkov, Otto Chmelk, and Jan Nmec in Dn; Vladimr Kaiser in st nad Labem; and archivists and staff in Most, Kada, Teplice, and Liberec. And in Prague, Dalibor Sttnk of the Archive of the Ministry of Interior.

I want to give special recognition to Istvn Dek, my doctoral adviser at Columbia University in the 1990s. His probing questions, clear writing, and moral compass remain an inspiration to me and to two generations of historians of Central and Eastern Europe.

Earlier versions of chapters have appeared as journal articles. Though Ive made significant additions and changes, I want to acknowledge and thank the journals Central European History, Environment and History, the Journal of Contemporary History, and the Journal of Modern History for publishing and allowing me to reprint parts of my work. Full citations appear in the bibliography.

Last, but certainly not least, I want to thank my wife, Amy Vozel, and our two spirited daughters, Sierra and Acadia. Weve hiked, snowshoed, sledded, playgrounded, kayaked, and read all sorts of wonderful books together. Sierra has recently taken an interest in my work and asked mewhat this book was about. I said, people and a church that moved. And she understood, sort of, because we have moved too. And shes seen the church that moved, in the Czech Republic, and who wouldnt be amazed by that?!

Introduction

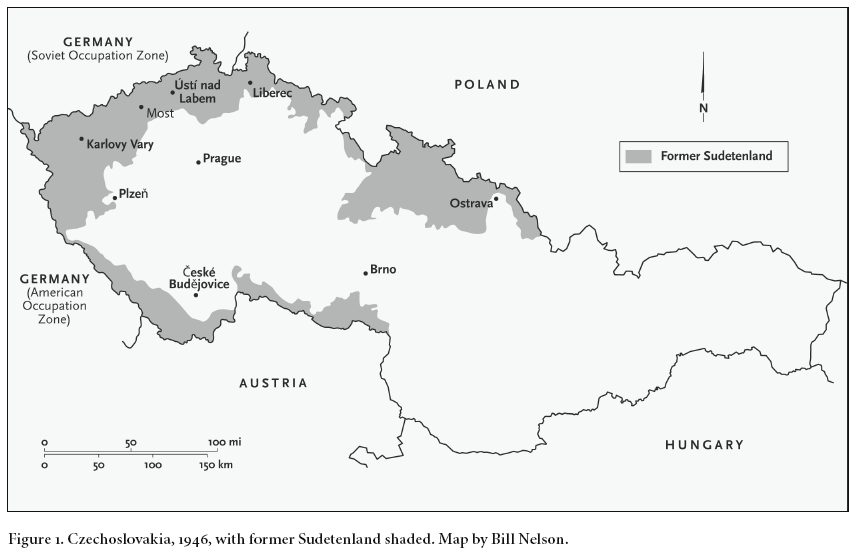

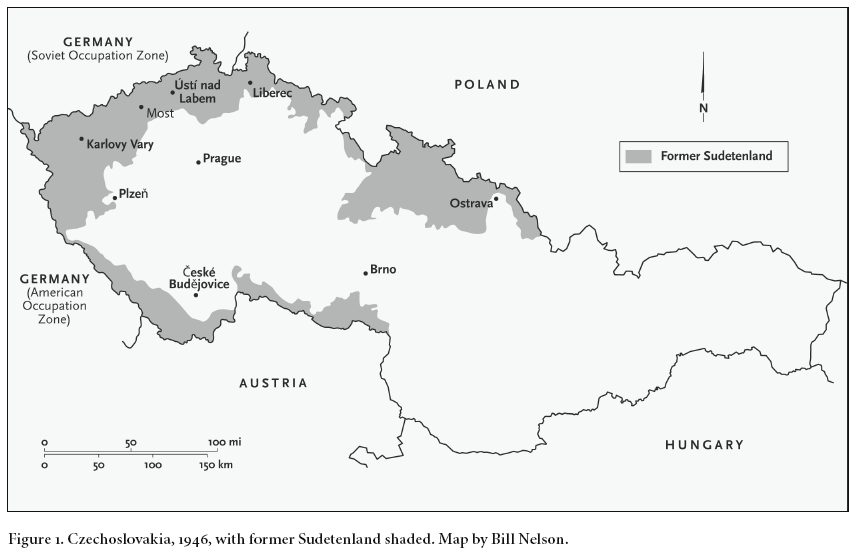

Dit, Bohumil Hrabals Czech protagonist in I Served the King of England, longed to be buried in the forsaken German graveyard, perched on a hill, straddling the great divide between the Danube and Elbe river basins. The graveyard lay in a remote corner of the Czechoslovak borderlands, the former Sudetenland, cleansed of its German population after the war ended in 1945. Dit went to the borderlands to start a new life, to escape his own sense of inferiority and the taint of collaboration with the defeated Nazis. But he couldnt escape the past in the haunted landscapes of the borderlands. Drinking from a stream below the abandoned cemetery, Dit could taste the dead buried long ago in the graveyard. Not only the water but also mirrors held the imprints of the Germans who had looked into them, who had departed years ago.... As with the departed in the drinking water, Dit mused, I rubbed shoulders with people who were invisible... and I kept bumping into young girls in dirndls, into German furniture, into the ghosts of German families.

But these were not ordinary ghosts. Typical ghosts are distant memories, projections within the present of an unsettled past. Most of the departed Germans were still alive, settled just across the border in West and East Germany. Expelled in the aftermath of the Second World War, around three million Czechoslovak Germans had joined millions of other expelled Germans from the east in the largest wave of forced migration in history. Czechoslovakias Germans grudgingly made new homes in a Germany scarred by war and pacified by occupation. Though cut off from their former homes by international borders hardened by the Cold War, expelled Germans vigorously engaged their lost homelands in] (homeland) gatherings and publications, as well as political speeches and Cold War propaganda.