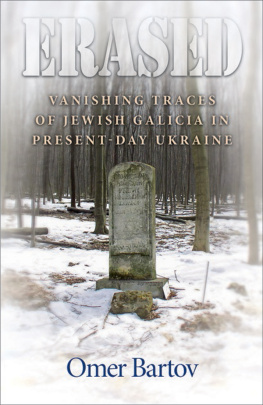

TALES FROM THE BORDERLANDS

TALES FROM THE BORDERLANDS

Making and Unmaking the Galician Past

OMER BARTOV

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2022 by Omer Bartov.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please email (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021951341

ISBN 978-0-300-25996-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memoriam

Alan Mintz, 19472017

and

Esti Amit (Eichenwald), 19542019

Contents

Preface

T HIS BOOK TELLS A largely forgotten story through the lens of first-person history. The story it tells is of a place and a civilization that vanished in the wake of World War II. The place was Europes vast eastern borderlands, stretching from the Baltic to the Balkans, where the emerging great empires of the early modern period expanded, overlapped, clashed, and disintegrated. The civilization was by its very nature a mix of multiple cultures, languages, ethnic groups, religions, and eventually nations. They too often overlapped, clashed, and were ultimately brutally sorted out in a manner that sucked out the spirit of the borderlands that had previously animated them.

Telling this story in its entirety is impossible, and attempting to do so would also deprive it of what makes it both fascinating and unique. It is an important story because in many ways it traces the emergence of our own contemporary world from a distinctly different reality. We tend to regard the past as nothing more than a gateway to our more progressive and evolved present. But erasing or marginalizing the past means that we not only fail to understand the present but also do not know what we have lost. The point is not that we can go back in time, but rather that we can learn how life was led and understood in the past and why what we have created for ourselves may not at all be the best version of human civilization. But that borderlands world, which was one of the breeding grounds of the modern age of nations, is too vast and complex to be taken as a whole. Nor is there any need to do that. Instead, we can sample some parts of it, look at them more closely, examine them in the light and in the shade, listen to their sounds more carefully, and interrogate what they have to tell us that we have forgotten, if we ever knew.

Still, even by examining only a small segment of that world, we may find ourselves mired in the kind of endless demographic, ethnographic, and bureaucratic data that obscure even as they quantify the spirit of a civilization. And, in any case, they do not tell a story, which is what this book hopes to do. For this book wants to tell history as a story, and to tell that story as a first-person history. By first-person history I mean history with a lowercase h. It is the history of the men and women who populated the universe of the borderlands, their fates and hopes, dreams and disillusionment. It is also a history of the stories they told themselves and others about who they were, where they came from, and where they were heading. In this sense it is both a history from below and a history from within. It tells us about the protagonists of this world, those who lived and experienced it, rather than those who ruled and subjugated it, and it tells us what they thought, believed, and felt, in their own words. These people may or may not be typical or representative, but they represent the world in which they resided in fascinating and at times profound ways.

Because I envision this book as a new exercise in writing history through a first-person prism, it is also a personal book. It is personal in that it is concerned with the mentality and emotions of real and fictional people. It is also personal in the sense that I have a personal, indeed an intimate relationship to that world, even though it vanished before I was born. In that sense it was only natural for me to end this book with my own mothers first-person account and her transition from that world on the eve of its destruction to the new world of Palestine on the eve of its re-creation as the Jewish state. This personal link between me and the world I write about through my mothers story makes it into my own first-person history, which is, I think, the only way to delve into this territory in the first place, that is, from within ones own biography, or, perhaps, ones heart.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1569. Chris Erichsen, cartographer.

Galicia through the ages. Chris Erichsen, cartographer.

TALES FROM THE BORDERLANDS

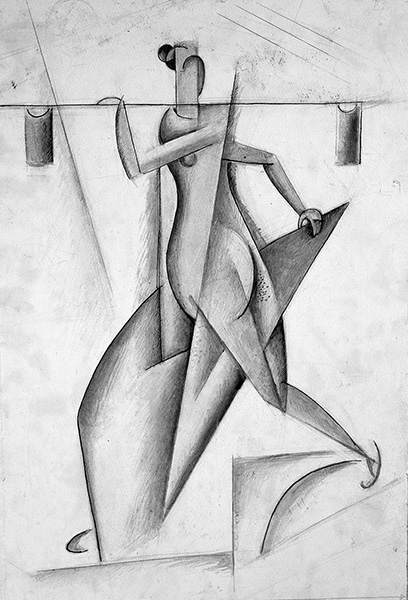

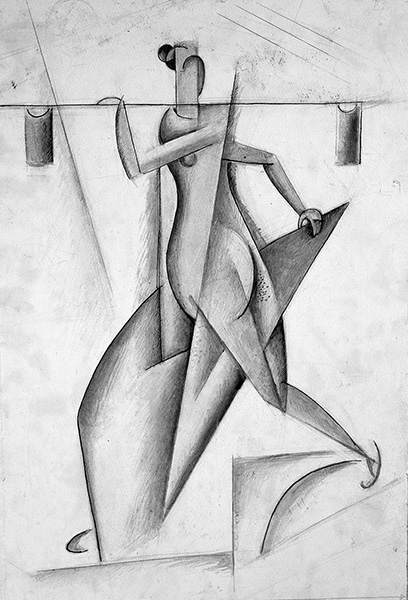

Mark Epstein, Woman with a Yoke, 1920s. Used by permission of the National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Introduction

Out into the World (Before the Apocalypse)

T HE THREE GENERATIONS BORN between the Spring of Nationsthe revolutions of 1848 that swept across Europeand the outbreak of World War I in 1914 lived through a time of rapid economic, social, political, and cultural changes. These were decades of growing hopes for a better future, in which political liberalization, greater freedom of movement, and new-fangled ideas about peoples ability to break the chains of traditional family, community, and religious authority and to redefine themselves in previously unheard-of ways filled the hearts of youngsters with a sense of adventure and unlimited possibilities. Yet by the end of this period, a newly emergent nationalism that was intolerant, aggressive, and militant succeeded in mobilizing large numbers of the increasingly impatient younger cohorts, whose hopes for change had been repeatedly dashed by a traditional elite loath to relinquish its power. The war that broke out unleashed death and devastation on a scale that no one could have foreseen. None of the survivors of the slaughter was unscathed by its horrors, and the generations that followed them were of a very different breed, less hopeful and nave, more cynical and uncompromising than the men and women of the pre-1914 world of yesterday, as the Jewish-Austrian author Stefan Zweig called it in a book written shortly before he committed suicide in exile in 1942.imagine the world that existed before that time, and the men and women who lived in it. Yet it was their hopes and dreams, twisted and perverted into the stark realities of industrial warfare and genocide, that were at the root of it all.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the case of eastern Europes former borderlands, that shatterzone of empires, where the German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman Empires touched each other along a vast swath of territory populated by people of multiple ethnicities and religions, languages and traditions. From the point of view of the empires they belonged to, these regions were on the periphery, made up of a bewildering mix of humanity of dubious loyalties. From the perspective of the inhabitants of the numerous villages, towns, and cities of the borderlands, the empires were distant, somewhat amorphous entities, whose representatives, when they appeared, were perceived as disrupting their traditional way of life for no particular reason. The empires sought to understand the nature and characteristics of the people residing in these borderland territorieswhich were usually annexed in the course of a larger political or military event of which the local population knew very little. As they were categorized and counted, divided into groups, and assigned particular characteristics by imperial agents and a host of curious ethnographers, the people of the borderlands, who had lived side by side since the Middle Ages, began seeing themselves through the lens of their observers. Internalizing the qualities attributed to them by outsiders, the borderlanders also began identifying more clearly and antagonistically what distinguished them from their neighbors beyond the traditional religious, linguistic, and socioeconomic differences.

Next page