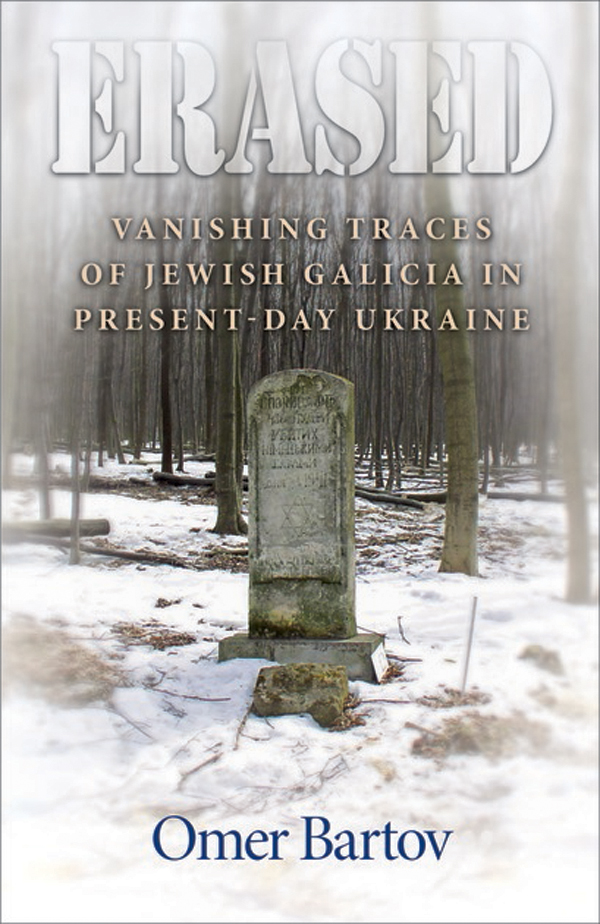

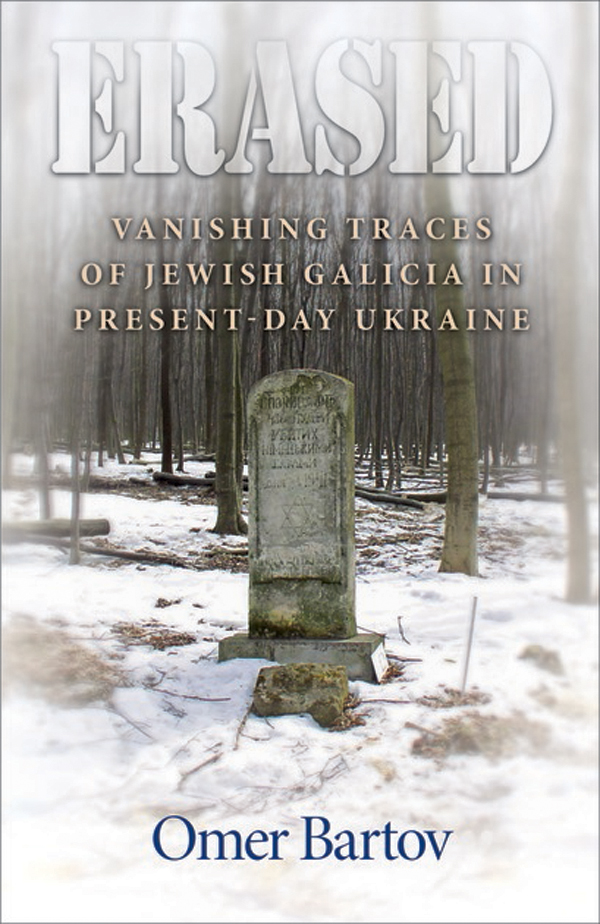

Erased

___________________

Erased

VANISHING TRACES OF JEWISH GALICIA IN PRESENT-DAY UKRAINE

Omer Bartov

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2007 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

A LL R IGHTS R ESERVED

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartov, Omer.

Erased : vanishing traces of Jewish Galicia in present-day Ukraine / Omer Bartov.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13121-4 (alk. paper)

1. JewsUkraineGalicia, EasternHistory20th century. 2. JewsUkraineHistoryGalicia, Eastern21st Century. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)UkraineGalicia, EasternInfluence. 4. Galicia, Eastern (Ukraine)Ethnic relations. I. Title.

DS135.U4B37 2007

305.892404779dc22

2007017231

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Typeface

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

I N REMEMBRANCE OF Ilona Karmel (19252000), FRIEND, MENTOR, MODEL

I realize that your time in Cracow will be limited and that you both want and have to concentrate on the Jewish life there. But this is precisely my point: Jewish life, especially the life of the generation born around and shortly after World War I, took place not only, not even primarily in Kazimierz (the Jewish Quarter) but in the entire city. So that what Cracow represented became a part of us.

From a letter by Ilona Karmel sent to me on June 2, 1997, shortly before my first trip to Eastern Europe

Ilona was born in Cracow and spent the war in the citys ghetto and in many labor and concentration camps. She subsequently came to the United States and published two outstanding novels based on her experiences during the Holocaust and her recovery from severe injuries at the end of the war: Stephania (1953), and An Estate of Memory (1969). She was an extraordinary woman and a great writer, and anyone who wishes to understand the term crimes against humanity should read her largely forgotten novels.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T HIS LITTLE BOOK has deep biographical roots. It is also the first modest fruit of a long journey that began many years ago and has not yet ended. While it is not about its author, I cannot deny being more invested in it than in any of my previous historical writing. This is a story of discovery of what there once was, what has remained, and what has been swept away. This discovery was my own because when I began this journey I knew very little. Others who knew much more could no longer speak, or would not tell, or, most commonly, told only their own tales. I traveled into what was for me a white space on the map; there was a sense of adventure in this undertaking akin to what I felt when I read as a child about the great explorers of previous centuries. But it was also a journey into a black hole that had sucked in entire civilizations along with individual and never-to-be-met family members, making them vanish as if they had never existed, just as those explorers of old ended up transforming the white spaces on their maps into colonial hearts of darkness.

I spent much of my childhood and youth in a small neighborhood in northern Tel Aviv. Israel of the 1950s was poor, provincial, and isolated from the rest of the world. On a nearby hill stood the remnants of a Palestinian village whose inhabitants had fled during the fighting of 1948. It was populated by Jewish refugees from North Africa who had been expelled from their homes by Arabic regimes. My own neighborhood was soon inhabited by Jews expelled from Poland by the anti-Semitic postwar Gomuka regime, mostly survivors of the Holocaust and their children. Polish could be heard everywhereat the grocers, the barbershop, the bank, and the post office. In my own home only Hebrew was spoken with the children. My father was born in Mandatory Palestine; my mother came from Poland as a child in 1935. But Yiddish was always an alternative, whether it provided expressions that Hebrew lacked or because it allowed grown-ups to speak about forbidden issues in front of their children. And because my mothers family came from Galicia, there was also Polish, Ukrainian, and some Russian, all blended together into a soft, foreign, but intimately familiar sound that still echoes in my head.

My generation, born in the 1950s, rejected this foreignness. We were socialized into a new Israeli society; our language was hard, direct, crisp Hebrew. We had no patience for the endless storytelling and punning of Yiddish, which seemed to us to be all about rhetoric and never about action, always observing reality by analogy and responding to events by recalling the past. As for Polish, it was the language of plump aunts with too much lipstick and rouge and of powerful vodka-drinking gentiles with Jewish blood on their hands. For us, enclosed in a narrow land surrounded by barbed wire and sea, the opening to the world was English: the language of pop music, long hair, and sexual liberation. It carried no echoes of ghettos, pogroms, and exile. Yet the sounds implanted in a childs mind rarely vanish; at some point in ones life they return, gently prodding, subtly directing the now middle-aged man to look back and listen to the inner voice of his past, to ask the questions that had never been posed: where, when, why, how?

I knew close to nothing about my mothers hometown. In fact, I knew very little about the world she came from, although I learned more and more about the manner in which it was destroyed. I spent many years studying modern German history, and especially that of the Third Reich. Thanks to my Israeli upbringing, I had internalized a great deal of knowledge about the Holocaust and at the same time rejected it as a subject of scholarly investigation: it was too close and traumatic to allow the necessary distance and had been manipulated politically too much to be salvaged from layers of empty rhetoric and demagogy. It was only in the late 1980s, when I came to the United States, that I felt liberated from these constraints to study the genocide of the Jews.

But I remained constantly disturbed by two aspects of the field that was quickly developing into Holocaust Studies. First, I felt that studying the manner in which the Jews were killed told one very little about the manner in which the Jews had lived; in fact, it brought them into history for the sole purpose of depicting their extermination. Second, it became increasingly clear to me that there was a vast gap between those works that reconstructed the planning and execution of the final solution of the Jewish question by the Nazi regime and its agents, and those that reconstructed the lives and deaths of the Jews in their towns, in the ghettos, and in the camps. It was as if the very same Nazi insistence on separating the perpetrators and their victims had also infected the historians writing about that period.

In 1996 I visited two seminars on the Holocaust in Germany. These classes were ably taught by distinguished scholars; the bibliographies were extensive, the many students attending were serious and studious, the presentations in class were well informed and well argued. But everything the students read and wrote had to do with the German perpetrators; not a single reading concerned the victimsnot one testimony, one memoir, one historical reconstruction of Jewish life or death from a Jewish perspective. As I realize now, and did not then, there was also nothing about the world in which much of the killing took place, the social and political context of Eastern Europe. The Germans were studying how Germans exterminated Jews, even more tenaciously than Israelis were studying how Jews were murdered by Germans.

Next page