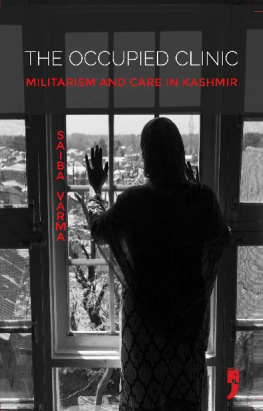

THE OCCUPIED CLINIC

The Occupied Clinic

Militarism and Care in Kashmir

SAIBA VARMA

For Nani,

who always knew how to put the world back

together

In this ethnography of people torn apart by the prolonged conflict in Kashmir, Saiba Varma carries us into the fraught zone of psychiatric practice and psychological aid. The Occupied Clinic skilfully unravels the complex imbrication between care and militarism, and between compassion and terror. Sharply observed and adroitly, often poetically, written, the book wears its considerable scholarship lightly, drawing its strength from a persistent engagement with the men and women who pass through the hospital and clinic. This is work that will be read by all those who are invested in the future of Kashmir, and its people, for it suggests that restraint and forbearance, borne like a wound and seen as the hallmark of the Kashmiri response to what has been inflicted upon them, must be seen as an ethical position, and a source of future strength.

Sanjay Kak

Filmmaker & Writer

Those familiar with Kashmir as the worlds most militarized zone often use it as a clinical fact, without visualizing Kashmiri lives. The Occupied Clinic , a thick account of the habitus of military occupation in Kashmir, corrects that easy imagining. It is a meticulously told story of how militarization wears down its prey with violence to their bodies, minds and hearts. Saiba Varma demonstrates that, in time, these violences intertwine to create a diabolical lattice-work. It chillingly tells us that militarized occupation is not mere domination, or even total control, but a frightful synthesis of simultaneous death-dispensing and life-giving, imprisonment and gentility, continuous uncertainty and calculated end-gaming that perplexes and disorients its quarry.

The Occupied Clinic is an indispensable work for anyone seeking to understand the ground realities in Kashmir devoid of dissociated sympathy, verbose ideology or negotiating table detachment.

Dr. Siddiq Wahid

Vice Chancellor of the Islamic University of Science and Technology

CONTENTS

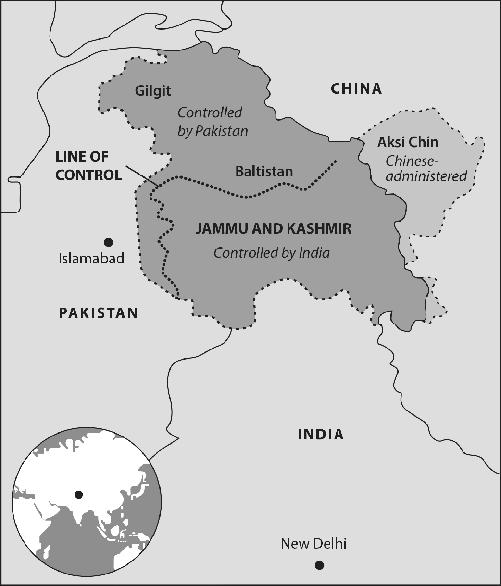

FIGURE P .1. Map of Kashmir

In translating spoken Urdu and Kashmiri in this text, I have provided diacritical markings only for long vowels (for example, zd ) in order to ease pronunciation for non-native speakers. In so doing, I have departed from a technically precise transliteration. I have avoided all diacritical markings on names, however, and followed convention.

It has become a clich to say that we are living in strange times. But what of those who have been living with lockdowns, curfews, and unexpected interruptions long before the world glimpsed a new normal?

In March 2020, people in Indian-controlled Kashmir were barely recovering from a seven-month long communication blackout that was put into place after the regions autonomy was revoked in August 2019 (due to the removal of Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution). Although Kashmiris are no strangers to communication blackouts, this one was long and extraordinarily severe, even by the standards of Indian rule. In March 2020, 4G Internet had not yet returned. People joked and complained, using their classic and well-honed dark humor, that 2G was their destiny.

Then, just as the dense fog of one lockdown lifted, anotherthe nationwide lockdown imposed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic on March 25began. Unlike much of the rest of the world, for whom lockdowns and curfews were new experiences, for people in Kashmir, the COVID-19 pandemic was simply a lockdown within a lockdown. People referred to it as the virus lockdown, a qualifier necessary to distinguish it from other lockdowns still in effect. Like the rolls of concertina wire that add new dimensionality to the surface of the Kashmir valley, the COVID lockdown layered new complexities and restrictions on top of more than 30 years of military and emergency rule. Not only were health services yet again crippled by the overlay of lockdowns, the ruse of security and care was once again used to accelerate military violence and settler colonial policies. In April 2020, when they thought no one was looking, New Delhi implemented a new domicile law that relaxed residency restrictions and opened up jobs and land ownership possibilities to outsiders. As one Srinagar resident powerfully stated, You call it a curfew or a virus lockdown, but the fact is that were under a brutal siege.

In Kashmir, COVID-19 is not merely a public health crisis, but is folded into a dominant nationalist and xenophobic imaginary as yet another security threat. The militarization of public healthwhether stories of people being beaten up for violating curfews or of students being carried to quarantine centers in military vans instead of ambulancesare abundantly clear, as are their long-term effects of eroding peoples trust in state institutions. Militarization has not paused. On the contrary, the pandemic has offered a cover so that military lockdowns, healthcare shortages, media blackouts and isolationcan occur under the cover of public healthcare. This, too, has a history, one which this book attempts to tell.

The COVID-19 lockdown is familiar, and yet not. The lockdown within a lockdown marks not an exceptional departure from, but rather, sharpens many of the themes present in The Occupied Clinic . This book grapples with how military logics transform possibilities of carein humanitarian and health infrastructures and everyday lifefor people in the region. It provides an ethical, social, and historical map to situate our contemporary moment, to understand how life under occupation is brutally undone, and how people find ways to go on. Throughout the book, stories of an otherwise bubble up : of people building relationships, providing ordinary and extraordinary acts of care, resting and resisting, joking, mourning and celebrating, demonstrating interdependence, and just being. Despite the infinitude of sieges, curfews, and (multiple) lockdowns, these everyday practices sustain hope for something more. Despite the severity of the COVID lockdown, there are plenty of forms of mutual aid that continue to flourishwhether volunteer ambulance drivers and healthcare workers or those performing last rites for victims of coronavirus on behalf of families. There are thousands more of these everyday acts that are happening all the time.

Meanwhile, a sense of exhaustion also seeps in. That exhaustion, a deep existential sigh, reminds us that care labor is not to be romanticized or merely glossed as resilience. These practices are not automatic. They stem from long histories of oppression, and they need to be nurtured if they are to survive. This book is one small effort among many to honor the everyday work of care that is central to processes of decolonization. Before the world knew of lockdowns, people in Kashmir had much to teach us about how to survive, enact care, maintain hope, and live well.

In centering historical and contemporary practices of decolonization through the vantage of care work, The Occupied Clinic is not just about others decolonization efforts; it is also an artifact of an effort to decolonize the discipline of anthropology and myself as a scholar. Anthropology, as is well known, has its epistemological foundations in colonialism. Anthropologists of the past and present continue to make possible imperial and colonial violence, in India, the US, and elsewhere.

SAIBA VARMA

SAIBA VARMA