THE CAPITALIST UNCONSCIOUS

THE CAPITALIST UNCONSCIOUS

FROM KOREAN UNIFICATION TO TRANSNATIONAL KOREA

HYUN OK PARK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHERS SINCE 1893

NEW YORK CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54051-3

This publication project was supported by the Korea Foundation.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Park, Hyun Ok.

The capitalist unconscious : from Korean unification to transnational Korea / Hyun Ok Park.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-17192-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-54051-3 (ebook)

1. Korea (South)Social conditions. 2. CapitalismSocial aspectsKorea (South) 3. Korea (North)Social conditions. 4. SocialismKorea (North) 5. Korean reunification question (1945-) I. Title.

HN730.5.A8P39 2015

306.34209519dc23

2015010090

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

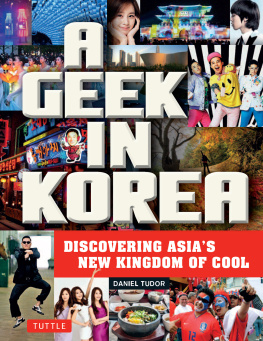

COVER IMAGE: Cho Chonhyun, Footsteps on the Border

COVER DESIGN: Chang Jae Lee

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Michael Burawoy and Harry Harootunian

CONTENTS

Korea is already unified in a transnational form by capital. The prevailing ability to overlook flows of people, goods, and ideas crossing the borders of South Korea, China, and North Koreabeyond economic aid and the widely publicized trail of North Korean refugeesattests to the continued reign of the Cold Wars legacy and a seemingly undeniable sense of capitalisms victory over socialism. Recognition of transnational Korea requires a historical approach that consigns the current Korean nation formation to the history of Korea and the Korean diaspora in the twentieth century. The ongoing transnational interaction of Koreans is constituted by asynchronous adoption of neoliberal reforms in Korean communities, each of which imagines them as a new democratic order. The Capitalist Unconscious presents the postcolonial and Cold War history of socialism and capitalism as the history of the neoliberal present. During the Cold War, rivalry between the two Koreas contrived their territorial integration as the normative vision of Korean ethnic and national sovereignty. Despite the tenacity of this Cold War formula, the current capitalist and democratic integration of Koreans across borders has once again destabilized ethnic and national relations of Koreans, which have been a vortex of the Asian order ever since the large-scale migration of Koreans to Manchuria (northeast China) and neighboring countries from Japanese rule. In turn, the unfolding disagreements over the identity and rights of border-crossing Koreans within each community and across them expose the unevenness and disjuncture of the current capitalist expansion on a global scale, which each Korean community construes as a transition from socialism to capitalism or from military dictatorship to democracy. The purportedly hegemonic spread of neoliberal capitalism is in fact the latest response of each Korean community to its singular crisis during the Cold War era that shaped nation formation, whether socialist or capitalist.

The border between North Korea and the world is not another Berlin Wall. The German model of national unification is not suitable for Korea. Unlike East Germany during the Cold War, two key forces have integrated North Korea into the global capitalist system in the postCold War era: Its new economic relationship with China and South Korea and the border-crossing migratory labor of North Koreans, both of which are inextricable from socioeconomic changes within North Korea. The German experience pertains to the Cold War context. Adopting it for Korea would mean disregarding the massive political, socioeconomic, and cultural changes in North Korea since the 1990s. North Korea and the United States and its allies may well agree on the importance of capital investment in North Korea. One might ask what is preventing us not only from recognizing that North Korea has already combined socialist ideology and capitalist economic development, as China has done, but also from accepting their consequent synergy that is to be determined by the society and the state. North Korea, in fact, has been on that thorny road for decades. Even if the North Korean regime falls in the near future, the politics and history of the neoliberal capitalist and democratic present discussed in this book will continue to inform an important strand of unfolding change in its society.

The booming field of North Korean studies regards the states capricious marketization and its clash with the peoples desire for privatization and democracy as the defining reality of North Korea in the current moment. However, this book interprets the latest conflict of the state and society as the newest instance of their repeated struggle to reconcile the continued contradiction between socialist construction and pursuit of rapid industrialization under postcolonial condition and national division. Given that this contradiction was integral to socialist experiences during the twentieth century, The Capitalist Unconscious provides a comparative account of North Korean socialism in light of the history of permanent and continued revolution in the Soviet Union and China. Todays politics concerning North Korea pits economic engagement with North Korea against protecting the human rights of North Koreans. Called the Sunshine Policy, trade and other forms of economic cooperation between the two Koreas are adopted as the means for peaceful reconciliation and gradual political change by progressive leftist South Korean governments. The protection of the human rights of North Koreans through the means of regime change is advocated by forces as various as South Korean and global NGOs, converted former proNorth Korean radicals, Christian evangelists, and the United Statesled war on terrorism. This political antinomy in the approach to North Korea obscures their consensus on the capitalist market system and the rule of law as cornerstones of democratization. The vehemently opposed proposals for North Korea are spectacles of neoliberal capitalism, in which Korean and global communities displace their own contradictions arising from capitalist consensus and deepened socioeconomic inequality at home onto the task of democratizing North Korea.

The neoliberal capitalist and democratic present in the Korean peninsula is entwined with the Korean Chinese community in northeast China through the cascading labor migration of Koreans from China to South Korea and from North Korea to China. In South Korea, Korean Chinese migrant workers provide cheap labor in caring of children, the elderly, and the sick, as well as in restaurants and karaoke places. Apart from working in coastal regions of China in factories owned by South Koreans, North Korean migrant workers not only farm land of Korean Chinese farmers who left for South Korea but also work in the thriving service sectors opened up by Korean Chinese with their remittances from South Korea. Neoliberal capitalist reforms ruptured the promise of a welfare society in South Korea; low-paid Korean Chinese labor contributes to maintaining its facade. Some Korean Chinese make sense of their experience of migratory work in South Korea by remembering the Chinese Cultural Revolution as intra-ethnocide. Remembrance in South Korea of this deeply repressed history authorizes an investigation into the Chinese revolution as the history of their present-day relationship with South Koreans. The double inversion of Koreans from anticolonial revolutionaries to counterrevolutionaries, and from partners of socialist internationalism to national enemies characterizes the tumultuous process of Koreans becoming a national minority in the Peoples Republic of China. The repeated construction of Koreans as others has coexisted with the history of Korean leadership during the anticolonial revolutionary struggle in Manchuria and Koreans extensive participation in the socialist construction. This paradox has unsettled their national identities and rights, although it is often shrouded by the ready-made narrative of the model minority. Constructed primordial attributes of Korean ethnicity supplied the