Arvind-Pal S. Mandair - Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation

Here you can read online Arvind-Pal S. Mandair - Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Columbia University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

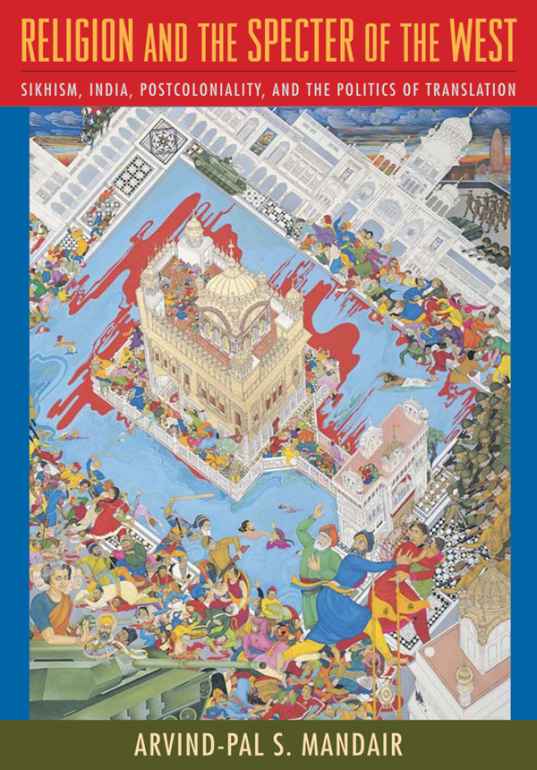

- Book:Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation

- Author:

- Publisher:Columbia University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

RELIGION AND THE SPECTER OF THE WEST

INSURRECTIONS

CRITICAL STUDIES IN RELIGION, POLITICS, AND CULTURE

INSURRECTIONS

CRITICAL STUDIES IN RELIGION, POLITICS, AND CULTURE

Slavoj iek, Clayton Crockett, Creston Davis, Jeffrey W. Robbins, editors

The intersection of religion, politics, and culture is one of the most discussed areas in theory today. It also has the deepest and most wide-ranging impact on the world. Insurrections: Critical Studies in Religion, Politics, and Culture will bring the tools of philosophy and critical theory to the political implications of the religious turn. The series will address a range of religious traditions and political viewpoints in the United States, Europe, and other parts of the world. Without advocating any specific religious or theological stance, the series aims nonetheless to be faithful to the radical emancipatory potential of religion.

After the Death of God , John D. Caputo and Gianni Vattimo, edited by Jeffrey W. Robbins

The Politics of Postsecular Religion : Mourning Secular Futures , Ananda Abeysekara

Nietzsche and Levinas: After the Death of a Certain God, edited by Jill Stauffer and Bettina Bergo

Strange Wonder: The Closure of Metaphysics and the Opening of Awe , Mary-Jane Rubenstein

RELIGION AND THE SPECTER OF THE WEST

Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation

Arvind-Pal S. Mandair

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2009 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51980-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mandair, Arvind-pal Singh.

Religion and the specter of the West : Sikhism, India, postcoloniality, and the politics of translation / Arvind Mandair.

p. cm. (Insurrections : critical studies in religion, politics, and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-14724-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-51980-9 (ebook)

1. Sikhism and politicsIndiaHistory. 2. Translating and interpretingPolitical aspectsIndiaHistory. 3. ReligionPhilosophy. I. Title. II. Series.

BL2018.5.P64M36 2009

294.6172dc22

2009020690

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

For Preet, Aman, and Sukhmani

This book has had a long and unusual development. The central issues with which it grapplesreligion, translation, subjectivity, and the politics of knowledge constructionfirst became an issue for me in the mid- to late 1980s, when significant sections of the Sikh community, within and outside India, were embroiled in an often violent conflict with the Indian state. With the global media thoroughly fixated on issues such as fundamentalism, sectarianism, and the unwelcome return of religion into the public domain, Sikhs and Sikhism were often in the media spotlight. By the time this conflict had peaked in 1992, not only was it routinely driving local Sikh politics in the UK and North America, as organizations fought for control of newly established political parties and institutions, but it had also spawned vigorous intellectual debate as many Sikhs, myself included, tried to come to terms with the events that had transformed them into a rogue community vilified by the state, media, and academic apparatus.

At the time I had just left the chemicals industry to take up an academic position researching superconductors. Despite constantly bemoaning this decisionas it would continue to deprive me of the intellectual tools and the time necessary to comprehend the complex relationship between state, media, and academia, particularly as it impinged on the representation of Sikhism on the one hand, and the production of Sikh subjectivity on the otherI was eventually able to embark on a program of retraining in the humanities while continuing my scientific research.

The discipline that initially attracted my attention was the history of religions, with an area focus on South Asian studies. I was interested specifically in the philosophical hermeneutics of Sikh scripture. Somewhat naively, I had hoped to find a way to reinterpret Sikh theology from a postcolonial perspective, thereby avoiding the growing impasse between traditionalist Sikhs and the strictly academic (phenomenological) perspective. While I never relinquished this task, I quickly discovered that any hermeneutic project had to acknowledge the encounter between Sikhism and the West in the nineteenth century, and particularly the politico-philosophical consequences of translating Sikh scripture into European languages. In other words, there was an important historical dimension to the emergence of Sikh theology and its enunciation as a part of modern Sikh identity. This realization dovetailed neatly with the work of some scholars of South Asian religions who at the time were producing ground-breaking social histories that suggested that the turn to religion in Sikh (and more broadly South Asian) politics could be traced back to the encounters between Sikhism (or India) and the West in the nineteenth century. This historical work provided support for the broader thesis emerging in the study of religions that the category of religion, defined as a set of beliefs and practices supposedly found in all cultures, dates from the modern period, during which Europe expanded its trade and established colonial networks throughout the world. The idea that the category of religion was, at least in some sense, fabricated in the nineteenth century found a convenient and useful ally in postcolonial theory, which helped to highlight issues of domination and power.

But while a combination of history of religions and postcolonial theory provided a useful critique of religion, it proved to be less useful thanand in some ways it firmly resisteda similar critique of the category of secularism. Indeed, both history of religions and postcolonial theory have maintained a doctrinaire adherence to the concept of secularism in the sense that the latter constitutes the very ground from which critique itself arises. This is best seen in the prevalence of historicism as the central methodology for these disciplines and in the general inertia involving any questioning of history. The root of this problem is that these disciplines view the distinction between religion and secularism in terms of a conventional narrative that states that modernity, humanism, and its offspring, secularism, constitute a radical break with prior traditions of thought, especially theology. What this story misses, however, is the essentiali.e., ontotheological or metaphysicalcontinuity between different moments in the Western tradition: specifically, the Greek (onto -), the medieval-scholastic (theo -), and the modern humanist (logos or logic ). The active forgetting of the ontotheological continuity between religion and secularismthe religious nature of the formation called the secular, or the secular nature of the formation called religionhas, however, been thoroughly probed by the discipline that has come to be called continental philosophy of religion. With its parallel critiques of secularism and religion, continental philosophy of religion proved to be a somewhat unlikely though useful ally in my attempts to understand the various turns toward, or the returns of, religion in India.

Despite the obvious cultural and intellectual tensions between these three divergent disciplinesthe material of continental philosophy of religion is drawn almost exclusively from the European philosophical and religious traditions, while history of religions and postcolonial theory apply themselves to non-Western cultures alsoit was possible to harness these differences by focusing on the intellectual encounter between India and the West made possible by European imperialism. This intellectual encounter must be considered a form of contact, that is, a social relation capable of transforming both parties in the encounter. As such this imperial encounter cannot be examined unless some attention is given to the problematic of translation. By doing so I was able to formulate a doctoral thesis, entitled Thinking Between Cultures: Metaphysics and Cultural Translation, which laid the basis for the present book. This was by no means a straightforward task, for it required forging an idiom that tested the limits of normal multidisciplinary practice. As I soon discovered when presenting or publishing earlier versions of my work at conferences and in journals related to these respective disciplines, continental philosophers (and philosophers of religion) showed little or no interest in reading materials that they considered to be too specialist (i.e., non-Western) and that belonged, properly speaking, to ethnic or area studies. Likewise, scholars in South Asian, and especially Sikh, studies tended more often than not to regard my engagements with continental philosophy, theology, and critical theory as either superfluous to the real labor of producing and interpreting archival data, or simply irksome insofar as my investigations were also attuned to the politics of knowledge production. And postcolonial theory, as I mentioned above, simply avoided any attempt to blur the lines between religion and secularism.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation»

Look at similar books to Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.