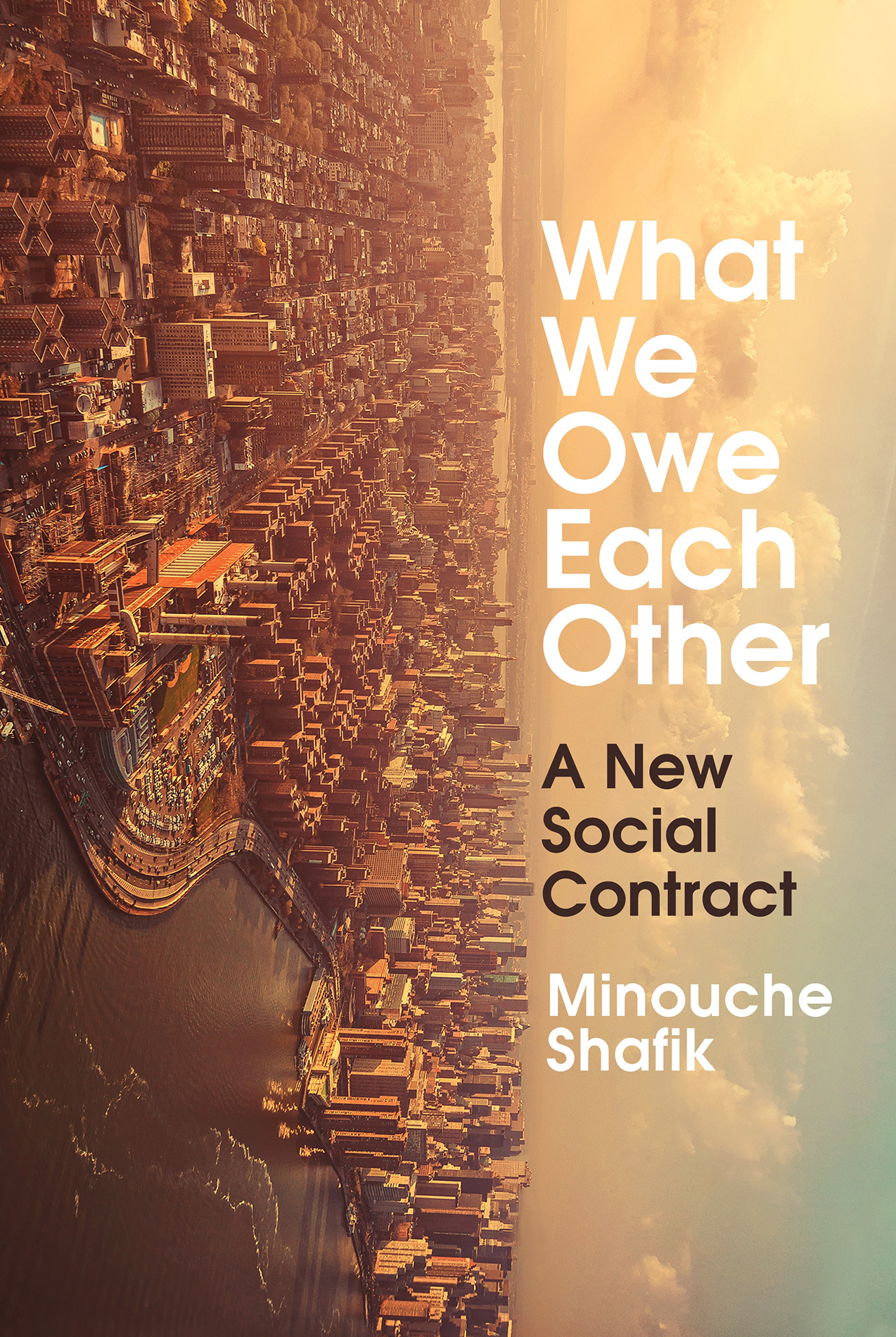

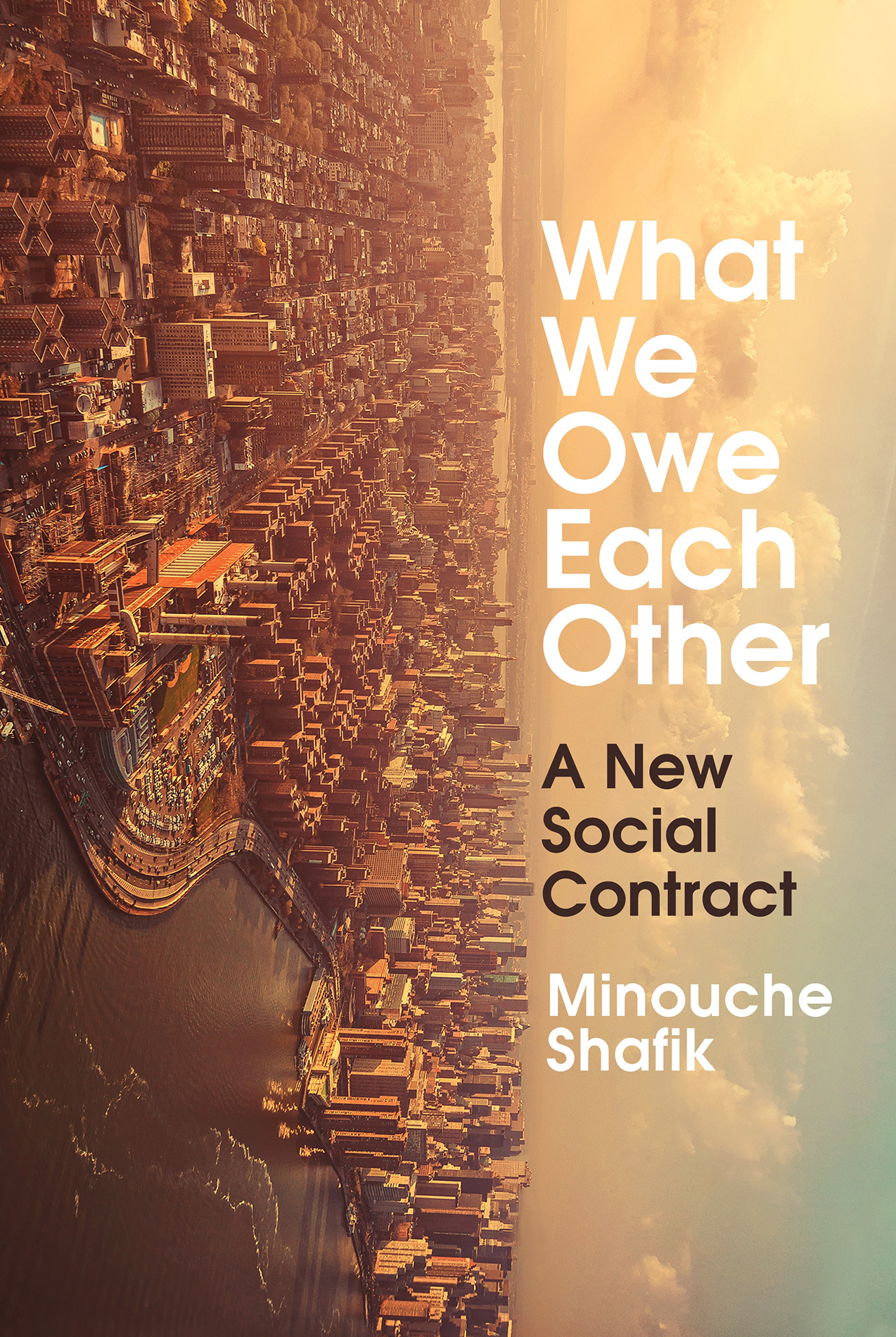

Minouche Shafik

What We Owe Each Other

A New Social Contract

Contents

About The Author

Nemat (Minouche) Shafik is Director of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Born in Egypt, she emigrated as a child to the USA, later moving to the UK for post-graduate studies in economics. At 36, she become the youngest ever Vice President of the World Bank and has since held positions as Permanent Secretary of the UK's Department for International Development, Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund and as Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, working on major policy upheavals across the globe, from the fall of the Berlin Wall, to the Arab Spring, to the financial crash in 2008 and the Eurozone crisis. Following her appointment as Director of the LSE in 2017, she launched a programme of research, Beveridge 2.0, to rethink the welfare state for the 21st century. She was made a Dame in the Queen's Birthday Honours list in 2015 and in 2020 was appointed a cross-bench peer in the House of Lords.

For Adam, Hanna, Hans-Silas, Maissa, Nora, Olivia and Raffael

Illustration Notes and Credits

Figure 3. Income shown is real purchasing power parity. Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic, Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession, World Bank Economic Review 30:2, 2016, pp. 20332.

Table 1. The high private return to primary education in high-income countries is due to an outlier 1959 estimate of 65% for Puerto Rico, a country classified as high-income under our current-per-capita income classification system. George Psacharopoulos and Harry Patrinos, Returns to Investment in Education: A Decennial Review of the Global Literature, Policy Research Working Paper 8402, World Bank, 2018.

.

.

Figure 9. Irene Papanicolas, Alberto Marino, Luca Lorenzoni and Ashish Jha, Comparison of Health Care Spending by Age in 8 High-Income Countries, JAMA Network Open, 2020, e2014688: https://doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14688

Table 2. WEF, The Future of Jobs Report 2018, World Economic Forum, 2018.

Figure 10. Truman Packard, Ugo Gentillini, Margaret Grosh, Philip OKeefe, Robert Palacios, David Robalino and Indhira Santos, Protecting All: Risk Sharing for a Diverse and Diversifying World of Work, World Bank, 2019: https://doi:10.1596/9781-4648-1427-3. Used under CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Figure 14. Base of 18,810 adults aged 16 years and above in 22 countries, fieldwork conducted SeptemberOctober 2016. Fahmida Rahman and Daniel Tomlinson, Cross Countries: International Comparisons of Intergeneration Trends, Intergenerational Commission Report, Resolution Foundation, 2018.

Figure 15. IMF, Fiscal Monitor: Policies for the Recovery, International Monetary Fund, October 2020.

Figure 16. Shunsuke Managi, and Pushpam Kumar, Inclusive Wealth Report 2018, 2018 UN Environment, Routledge, 2018. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group.

Figure 18. Truman Packard, Ugo Gentillini, Margaret Grosh, Philip OKeefe, Robert Palacios, David Robalino and Indhira Santos, Protecting All: Risk Sharing for a Diverse and Diversifying World of Work, World Bank, 2019: https://doi:10.1596/9781-4648-1427-3. Used under CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Acknowledgements

Not surprisingly, I owe many people a great deal in helping me write this book.

The idea of writing a book was planted by Rupert Lancaster after he attended a lecture I gave at the Leverhulme Foundation in 2018. At LSE, I benefited from being surrounded by people who are interesting and interested, starting with my colleagues in the Schools Management Committee and Council. Many colleagues shared ideas and provided generous comments on early drafts, and I am particularly grateful to Oriana Bandiera, Nick Barr, Tim Besley, Tania Burchardt, Dilly Fung, John Hills, Emily Jackson, Julian LeGrand, Steve Machin, Nick Stern, Andrew Summers, Andres Velasco and Alex Voorhoeve. Several friends and former colleagues pointed me to relevant literature, provided helpful comments and much-needed encouragement: Patricia Alonso-Gamo, Sonya Branch, Elizabeth Corley, Diana Gerald, Antonio Estache, Hillary Leone, Gus ODonnell, Sebastian Mallaby, Truman Packard, Michael Sandel and Alison Wolf. I owe them gratitude for their good ideas; any errors are exclusively mine.

Max Kiefel provided outstanding research assistance, finding interesting material and helpful suggestions even though we only managed to meet in person once because of the pandemic. James Pullen, my agent at Wylie, helped me navigate the world of publishing and was a constant source of good advice. Will Hammond, my editor at Penguin Random House, encouraged me to avoid academic jargon and helped make the text far more readable. Joe Jackson at Princeton University Press also gave helpful feedback.

I owe so much to my mother Maissa, who drove me to all those libraries and always supported me, come what may. I am grateful to my sister Nazli, niece Leila and my vast extended family, who provide a wonderful example of a social contract that is generous and enables everyone. To my husband Raffael, I owe thanks for making me braver and encouraging me to take on ever bigger challenges. Our children Adam, Hanna, Hans-Silas, Nora and Olivia were uppermost in my mind as I wrote the chapter on the intergenerational social contract. For them, and all our children and future grandchildren, I hope we manage to organise a better social contract for all of you to thrive.

Preface

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold Surely some revelation is at hand

So wrote W. B. Yeats in the wake of the horrors of World War I as his pregnant wife lay gravely ill from the 191819 flu pandemic. The phrase things fall apart was quoted more often in 2016 than at any time in previous years.

Over these recent years, I have seen many of the assumptions and increasingly the institutions and norms that have shaped my world fall apart. I spent 25 years working in international development and witnessed first hand how making poverty history resulted in huge improvements in peoples daily lives. Humans really have never had it so good. And yet in so many parts of the world, citizens are disappointed, and this has revealed itself in politics, the media and public discourse. Rising levels of anger and anxiety are associated with people feeling more insecure and lacking the means or power to shape their future. Support for the system of international cooperation that has existed since the post-war period, and in which I spent much of my career, is also waning as nationalism and protectionism come to the fore.

The global pandemic of 2020 brought all of this into sharp relief. The risks that the poor, those in precarious work and those without access to health care were exposed to were laid bare. The interdependencies between us were revealed as essential workers were largely the lowest paid without whom our societies could not function. We could survive without bankers and lawyers, but grocers, nurses and security guards were invaluable. The pandemic revealed how much we depended on each other for survival but also for behaving in socially responsible ways.

Next page