DOES SKILL MAKE US HUMAN?

Does Skill Make Us Human?

MIGRANT WORKERS IN 21ST-CENTURY QATAR AND BEYOND

Natasha Iskander

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON&OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number 2021940598

ISBN 978-0-691-21757-4

ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-21756-7

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-21758-1

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Meagan Levinson and Jacqueline Delaney

Production Editorial: Jill Harris

Cover Design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Brigid Ackerman

Publicity: Kate Hensley and Kathryn Stevens

Copyeditor: Cindy Milstein

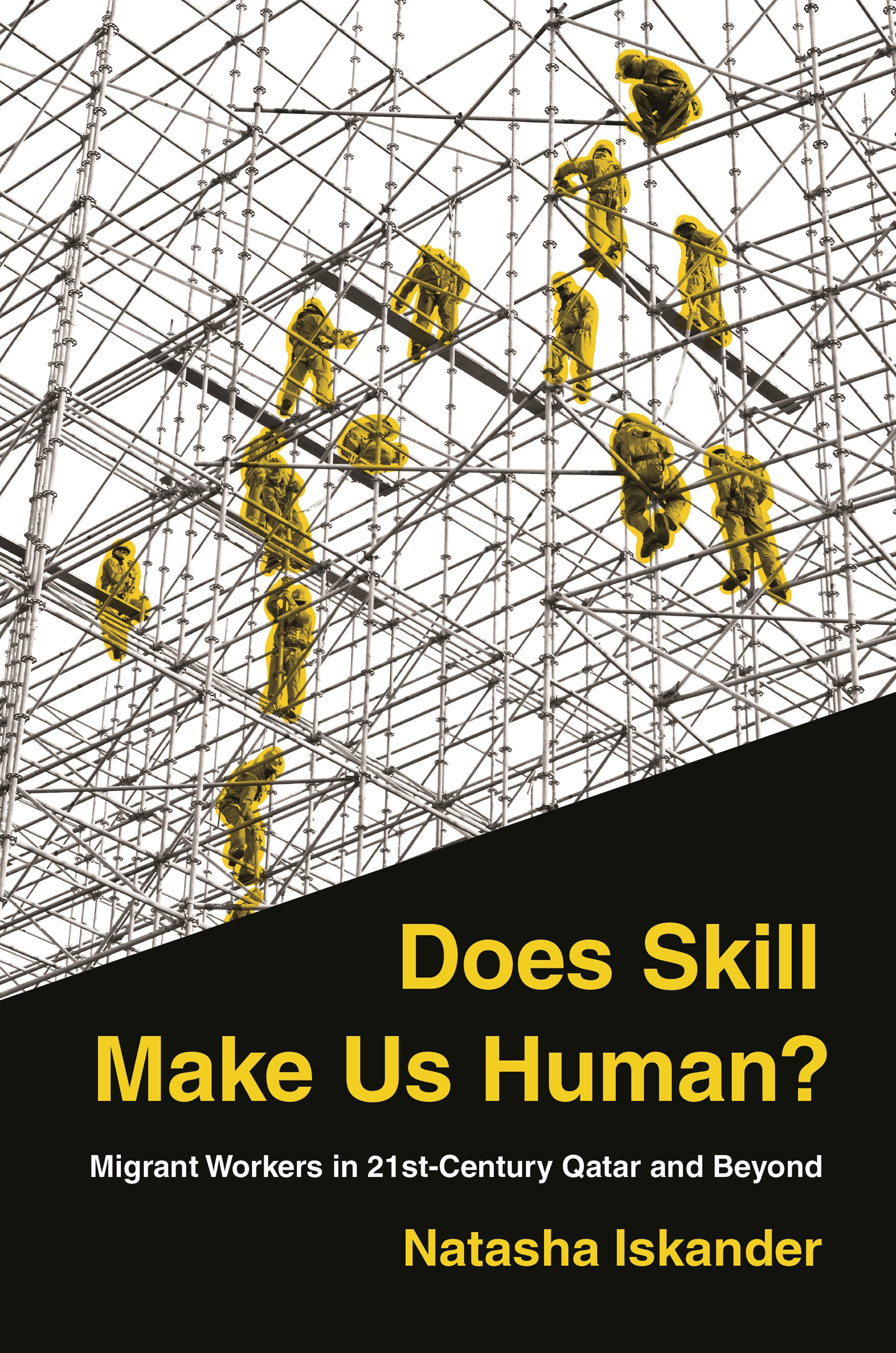

Cover image: Scaffolding construction being erected in Central Doha, Qatar. Photo: Gavin Hellier / Alamy Stock Photo

For Magdi Rashed Iskander,

father and friend

CONTENTS

- 1

- 313

DOES SKILL MAKE US HUMAN?

Introduction

THE MEN RAN. They ran in the clothes they had: jeans and flip-flops, or work boots. Some men, their feet cut up, abandoned their plastic sandals on the side of the road and ran barefoot on the hot pavement. They ran in the heat of the afternoonwith temperatures well into the mid-80sF and the air humid. They ran past the police lined up on the side of the road. In places, they ran past tables with bottled water, but the water had been left out in the sun and was hot and undrinkable. They ran for a long timemaybe hours. Their jeans chafed their skin. Their lungs burned, and their muscles cramped. A few collapsed. Many tried to step off the road, to stop running and rest, but they were forced back, yelled at that they needed to finish the race.

The men, many thousands of them, had been press-ganged to run the Qatar Mega Marathon 2015, organized in Doha as an attempt to set a new world record for the race with the most runners. They fell many thousands short of the record.

The race was held on a Friday, the only protected rest day for workers. Buses picked the workers up in the early morning from their labor camps in the industrial area, a segregated zone in the desert where they were lodged. The Al Sadd Sports Club, which organized the race, later admitted that it had asked companies to encourage workers with decent jobs to take part, but insisted that participation was voluntary and appropriate running gear was made available to anyone who wanted it. Many of the workers bused to the marathon route would likely not have known that they would be expected to run a race. But all of them would have found it difficult to refuse. These workers were migrants. They worked in Qatar under a sponsorship system that gave their employers the ability to deport them without notice and for any reason. The photographs and footage of the race show South Asian and African men, massed at the starting line, wearing identical white T-shirts and running bibs marked with contestant numbers.

Still, some of the migrants refused to participate.

When I read the press coverage of the Mega Marathon, I was reminded of a field trip I had made to a construction site for an oil and gas facility in Qatar just a few months before. I was in Qatar studying workplace practices in the construction industry and the process through which workers developed skill on-site. As part of my fieldwork, I went to observe construction on a liquefied natural gas (LNG) train, where workers were building a section of the plant where natural gas would be pushed through a network of pipes and then cooled into a liquid so that it could be shipped around the world. The construction site in Qatars northern desert was massive. Tens of thousands of workers from different trades worked concurrently on different elements of the structure. Like other construction sites I visited in Qatar, it was frenetic and crowded. In many places, workers bunched up as they waited to walk through the narrow passageways marked out by scaffolds and ramparts. Throughout the day, I shadowed different tradesmostly scaffolders and welders.

In the afternoon, I went to one of the on-site welding workshops. Located in a large hangar-like structure, the workshop was a vast, multipurpose space: small subcomponents of the structure were welded in one corner, training to improve welding skills took place at another end of the hangar, and quality control and the verification of the integrity of welded seams took place in another quadrant. The Turkish director of the welding center, Mehmet, would later describe it to me in elegiac terms. This place is like my paradise. I have twenty-five years working as a welder. [Welding] is something that comes into your body. Its like your blood. I can just look from outside at the finished product, and I can see how the welder is doing. Even from the sparks, I can see his philosophy. I can see whether he is moving slow or fast, how much he understands the work.

The LNG train required welding that was flawless. The materials that would be pushed through the trains maze of pipes were highly volatile and flammable. To assess the welding quality, the center used an X-ray system. Visual testing is not enough, even on the best seams, explained Mehmet. Radiographic testing was essential because even slight discontinuities in the internal structure of the weld could have consequences that were catastrophic. There are many factors. If you weld in the high heat, the seam wont have integrity. If you are not confident, the seam wont have integrity. If we see even one problem, we retrain, added Mehmet. Natural gas and the potential for explosion meant there was no margin for error, and the center continually tested and reinforced the expertise of its workers, who were already incredibly adept.

Ordinarily, the center was busy and cacophonous, with hundreds of welders, supervisors, and apprentices at work. But the day I first visited, it was empty. There were two supervisors at the desks in the office at the entrance, a few workers were sweeping the floor, and a couple of others were quietly doing maintenance on machinery. The scaffolding manager who accompanied me that day asked where everyone was. Sporting match, answered one of the supervisors.

The company had scooped up hundreds of men from the welding hangar and sent them to this sporting eventperhaps a soccer game; the supervisor was unsure. Someone in the government had made the request. The company had supplied the workers to fill the bleachers in the audience so that the international press would not report an empty stadium in a country that wanted to position itself as a global sporting destination.

This kind of conscription of construction workers was commonplace in Qatar, although this was the first time I had observed it directly. By and large, companies viewed it as a tax, a request that disrupted production, but with which they had no choice other than to comply. Companies bused their workers from labor camps to the sporting facility where the workers would be used as props. The workers would be treated as bodies, press-ganged into whatever activity was required, perhaps in the heat, perhaps without sufficient access to water, food, or rest. The welders missing from the training center were also, undoubtedly, used in this way. And in the process, their humanity, like that of the migrants forced to run a half-marathon in flip-flops, was turned into something that was no longer clear or certain, something that was open to question. They are human as well, right?