Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

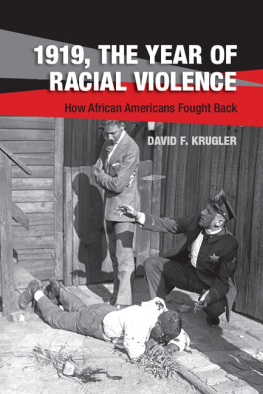

Phillips County, Arkansas 1919

A Union in Hoop Spur

The Path to Hoop Spur

The Red Summer of 1919

Helena

The Killing Fields

They Shot Them Down Like Rabbits

Photo Insert 1

Whitewash

The Longest Train Ride Ever

A Lesson Made Plain

Scipio Africanus Jones

The Constitutional Rights of a Race

I Wring My Hands and Cry

All Hope Gone

Photo Insert 2

Great Writ of Liberty

Taft and His Court

Hardly Less than Revolutionary

Thunderbolt from a Clear Sky

Birth of a New Nation

Epilogue

Appendix: The Killing Fields

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by by Robert Whitaker

Copyright

For Rabi, Zoey, and Dylan

Now their was a riot down here among the wrases and it was a Good many of Negros down their killed and the white Peoples called for the troops from Little Rock and they went down their and killed Negros like they wont nothen But dogs and did not make no arest on the whites whatever while they arested and unarmed a lots of Negroes and left the white with their armes and the Negro with nothen But their Hands and face to stand all the punishment that the white wished to Give them.

ANONYMOUS LETTER FROM A WORLD WAR I VETERAN TO

EMMETT J. SCOTT,

NOVEMBER 12, 1919

A Union in Hoop Spur

H OOP SPUR HAS LONG since disappeared from the maps of Phillips County, Arkansas, and even in 1919, when it could be found on such a map, it consisted of little more than a railroad switching station and a small store. But the cotton fields surrounding Hoop Spur were speckled with cabins, each one home to a family of sharecroppers, and on September 30 of that year, shortly after sunset, the black farmers began walking along dirt paths and roads toward a small wooden church located about one-quarter mile north of the switching station. For most, the church was a mile or two away, or even farther, and as they expected their meeting to run late into the night, they brought along sweaters and light coats for the walk back home. Many had their children with them, and a few, like Vina Mason, were carrying babies.

By 7:00 P.M., the first of the farmers had arrived, and they lit three lamps inside the Baptist church. The wooden benches began filling up rapidly. Sallie Giles and her two sons, Albert and Milligan, reached Hoop Spur around 8:00 P.M., and by then the house was packed, she said. Paul Hall was there, and so too were Preacher Joe Knox and Frank Moore, along with their wives. At last, Jim Miller and his wife, Cleola, pulled up in a horse and a buggy. Miller was president of the Hoop Spur Lodge of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union, which for the past several months had been signing up sharecroppers throughout southern Phillips County.

The one person still missing was the lodges secretary, Ed Ware. He was, as he later admitted, thinking of quitting. The previous Thursday, September 25, sharecroppers in Elaine, a small town three miles to the south, had held a Progressive Farmers meeting, which hed attended. The next day, white planters had singled him out and warned him not to go to any more such gatherings. He had reason to be afraid, but at last his wife, Lulu, insisted that they go, reminding him, as he later recalled, that I had those [union] books and papers. Although they lived only one mile to the west of the church, they had to swing around to the south in order to get past the Govan Slough, a ditch lined by a thicket of trees, and it was nearly 9:00 P.M. by the time they arrived. Ware nodded at the nine or ten men milling around front, and then he shook hands with Lit Simmons at the door, both men twisting their fingers into the lodges secret grip.

Weve just begun, Ware whispered.

That was the unions password, and everyone who had entered that night had uttered the same thing. Although the meeting was now in full swing, with, as one sharecropper put it, two hundred head of men, women and children inside, Simmons and the other men in the front yard remained where they were. William Wordlow, John Martin, John Ratliff, and Will Wright stood together in one group, about fifteen feet away from the door, while Alf Banks Jr., Albert Giles, and the three Beco brothersJoe, Boisy, and Ransomsat in Millers buggy. At first glance, it all seemed so peaceful. The church lamps cast the yard in a soft glow and the men were speaking in low voices, or saying nothing at all. But not too many yards distant, the light petered out, and everyone had his eyes glued to the road that disappeared into that darkness. Route 44, which ran north 22 miles to Helena, the county seat, was a lonely county road, bordered on both sides by dense patches of rivercane. In the buggy, the Beco brothers fiddled with shotguns draped across their laps, while several others nervously fingered the triggers of their hunting rifles. Martin was armed with a Smith & Wesson pistol.

At the door, Simmons was growing ever more nervous. This was only the third time that the Hoop Spur lodge had met, and at the previous meeting, which had been Simmonss first, hed asked why it was necessary to have men stand guard. White people dont want the union and are going to get us, hed been told. And on this night, Simmons knew, rumors were flying that whites were coming there to break up the meeting, or to shoot it up.

The minutes passed slowly by. Everyone listened for the sound of an approaching car, but the only noises that Simmons and the others heard, other than the chirping of field crickets, rose from inside the church. Nine-thirty passed without incident, then ten and ten-thirty. The road remained dark and quiet, and yet, to Simmons, it seemed that this night would never end.

The whites, he muttered, are going to kill us.

MOST OF THE HOOP SPUR farmers in the church that night were middle-aged, in their thirties, forties, and fifties, and their religious faith was such that they began all of their meetings with a prayer. They all had migrated here during the past decade, as this was about as deep in the Mississippi Delta as you could get, the cotton fields having been a tangle of swampland and dense hardwood forests only ten to fifteen years earlier. Southern Phillips County was a floodplain for both the White and Mississippi rivers, and as a result it had been about the last stretch of delta land in Arkansas to be drained and cleared. It remained an inhospitable place to live, the woods thick with fever-carrying mosquitoes, and yet it offered the black families a new hope. The two rivers had deposited topsoil so rich in minerals that geologists considered it perhaps the most fertile land in the world.

The Hoop Spur farmers were mostly from Mississippi and Louisiana, although a few hailed from as far away as North Carolina. Their journeys here had been much the same. Most had arrived during the winter months, just after the end of a harvest, as this was moving season for sharecroppers throughout the South. The black farmers almost always ended the year in debt, and so, hoping that it might be different someplace else, many packed up their meager belongings every couple of years and moved to a distant county or to another state. Most of those whod come to Hoop Spur had arrivedas a local scholar named Bessie Ferguson wrote in 1927with nothing of their own with the exception of their makeshift household furniture, a few ragged clothes, a gun, and one or more dogs, sometimes a few chickens or a hog.

Theyd moved into cabins that were, even by the dismal housing standards of the time, a sorry lot. Plantation owners threw up cabins made from rough lumber for their sharecroppers, each one surrounded by the plot of land that was to be worked by a family, and typically they were so poorly constructed that, as the joke went, the sharecroppers could study astronomy through the openings in the roof and geology through the holes in the floor. A sharecroppers cabin usually consisted of one large room, perhaps 18 by 20 feet in size, where the entire family would live and sleep, with a shed attached to the back. The main room would have a fireplace for heat and a couple of windowswith wooden shutters but no glassfor light. Because southern Phillips County was so vulnerable to floods, the landowners had erected cabins that were particularly flimsy, since they needed to be so cheap that the loss from floods is small, Ferguson said.

Next page