Linkography

Design Thinking, Design Theory

Ken Friedman and Erik Stolterman, editors

Design Things

A. Telier (Thomas Binder, Pelle Ehn, Giorgio De Michelis, Giulio Jacucci, Per Linde,and Ina Wagner), 2011

Chinas Design Revolution

Lorraine Justice, 2012

Adversarial Design

Carl DiSalvo, 2012

The Aesthetics of Imagination in Design

Mads Nygaard Folkmann, 2013

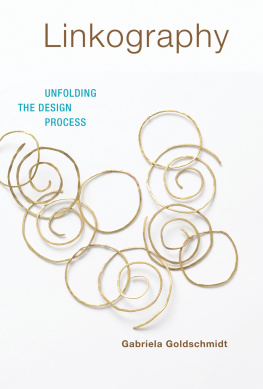

Linkography: Unfolding the Design Process

Gabriela Goldschmidt, 2014

Linkography

Unfolding the Design Process

Gabriela Goldschmidt

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goldschmidt, Gabriela, 1942

Linkography : unfolding the design process / Gabriela Goldschmidt.

p. cm.(Design thinking, design theory)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-02719-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-32216-4 (retail e-book)

1. Design Methodology. 2. Design Evaluation. I. Title.

NK1520.G64 2014

745.4 dc23

2013034867

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

for my late parents, Hedwig and Zeev-Wilhelm

Series Foreword

As professions go, design is relatively young. The practice of design predates professions. In fact, the practice of designmaking things to serve a useful goal, making toolspredates the human race. Making tools is one of the attributes that made us human in the first place.

Design, in the most generic sense of the word, began over 2.5 million years ago when Homo habilis manufactured the first tools. Human beings were designing well before they began to walk upright. Four hundred thousand years ago, they began to manufacture spears. By 40,000 years ago, they had moved up to specialized tools.

Urban design and architecture developed 10,000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Interior architecture and furniture design probably emerged with them. It was another 5,000 years before graphic design and typography got their start when Sumerians developed cuneiform.

Today all goods and services are designed. The urge to designto consider a situation, imagine a better situation, and act to create that improved situationgoes back to our prehuman ancestors.

Today, the word design means many things. The common factor linking them is service. Designers engage in a service profession. Their work meets human needs.

Design is first of all a process. The word design entered the English language in the 1500s as a verb, and the first written citation of the verb is dated 1548. Merriam-Websters Collegiate Dictionary defines the verb design as to conceive and plan out in the mind; to have as a specific purpose; to devise for a specific function or end.

The first cited use of the noun design can be traced back to 1588. The Collegiate Dictionary defines the noun as a particular purpose held in view by an individual or group; deliberate, purposive planning; a mental project or scheme in which means to an end are laid down. Today, we design large, complex processes, systems, and services, and to achieve this we design the organizations and structures that produce them. Design has changed considerably since our remote ancestors made the first stone tools.

At an abstract level, Herbert Simons definition covers nearly all instances of design. To design, Simon writes, is to devise courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones (The Sciences of the Artificial, second edition, MIT Press, 1982, 129). Design, properly defined, is the entire process across the full range of domains required for any outcome.

However, the design process is always more than a general, abstract way of working. Design takes concrete form in the work of the service professions that meet human needs. These professions include industrial design, graphic design, textile design, furniture design, information design, process design, product design, interaction design, transportation design, educational design, systems design, urban design, design leadership, and design management, as well as architecture, engineering, information technology, and computer science.

The various design professions focus on different subjects and objects. They have distinct traditions, methods, and vocabularies, used and put into practice by distinct and often dissimilar professional groups. Although the traditions dividing these professions are distinct, common boundaries sometimes form a border. Where this happens, they serve as meeting points where common concerns from two or more professions can lead to a shared understanding of design. Today, ten challenges uniting the design professions form such a set of common concerns.

Three performance challenges, four substantive challenges, and three contextual challenges bind the design disciplines and professions together as a common field. The performance challenges arise because all design professions act on the physical world, address human needs, and generate the built environment. In the past, these common attributes were not sufficient to transcend the boundaries of tradition. Today, objective changes in the larger world give rise to four substantive challenges that are driving convergence in design practice and research. These are increasingly ambiguous boundaries between artifacts, structure, and process; increasingly large-scale social, economic, and industrial frames; an increasingly complex environment of needs, requirements, and constraints; and information content that often exceeds the value of physical substance. These challenges require new frameworks of theory and method. In professional design practice, we often find that design requires interdisciplinary teams with a transdisciplinary focus. Fifty years ago, one designer and an assistant or two might have solved most design problems; today, we need skills across several disciplines, and the ability to work with, listen to, and learn from each other.

The first of the three contextual challenges is that design takes place in a complex environment in which many projects or products cross the boundaries of several organizations. The second is that design must meet the expectations of many organizations, stakeholders, producers, and users. Third, design has to deal with demands at every level of production, distribution, reception, and control. These ten challenges require a qualitatively different approach to professional design practice than was taken in earlier times, when environments were simpler. Individual experience and personal development were sufficient for depth and substance in professional practice. Though experience and development are still necessary, they are no longer sufficient. Most of todays design challenges require analytic and synthetic planning skills that cannot be developed through practice alone.

Professional design practice today involves advanced knowledge. This knowledge is not solely a higher level of professional practice. It is also a qualitatively different form of professional practice that emerges in response to the demands of the information society and the knowledge economy to which it gives rise.

In a recent article (Why Design Education Must Change, Core77, November 26, 2010), Don Norman challenges the premises and practices of the design profession. In the past, designers operated on the belief that talent and a willingness to jump into problems with both feet gave them an edge in solving problems. Norman writes:

Next page

![Wagner James Au [Wagner James Au] - Game Design Secrets](/uploads/posts/book/119431/thumbs/wagner-james-au-wagner-james-au-game-design.jpg)