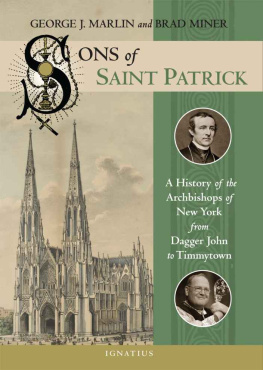

SONS OF SAINT PATRICK

George J. Marlin and Brad Miner

SONS OF SAINT

PATRICK

A History of the Archbishops of New York

from Dagger John to Timmytown

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations in this book have been taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Holy Bible, Second Catholic Edition, 2006. The Revised Standard Version of the Holy Bible: the Old Testament, 1952, 2006; the Apocrypha, 1957, 2006; the New Testament, 1946, 2006; the Catholic Edition of the Old Testament, incorporating the Apocrypha, 1966, 2006, the Catholic Edition of the New Testament, 1965, 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved.

Cover photographs from the Archives of the Archdiocese of New York

Used by permission

Cover design by John Herreid

2017 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-113-1 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-750-1 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2016941443

Printed in the United States of America

For our friend and colleague Robert Royal

CONTENTS

PART I

BEFORE THE BEGINNING

PART II

THE RISE TO POWER

PART III

THE CITY AND THE WORLD

PART IV

THE CHURCH IN CRISIS

INTRODUCTION

Not long after becoming the tenth archbishop of New York, Timothy Michael Dolan responded to a reporters question about how he was settling into the job by quipping that he had already learned how to order a hot dog from the cart outside the cathedral. It was a comment that won much affection for the new archbishop and furthered the sense that the Big Apple was now, as the New York Post had proclaimed, Timmytown . That is a very small example of what is necessary to fulfill the responsibilities of the job: the archbishop must know his city and be able to interact with its diverse people and media. And, really, it has always been so.

New Yorks first archbishop, the Irish-born John Joseph Hughes, became extremely skillful in his use of media, as we would say today, although his many memorable statements were not always as polished as Cardinal Dolans.

A comparison of the first and tenth archbishops also makes clear two things that are at the heart of this book. As our title suggests, every one of the men who has served as archbishop of New York has been Irish either by birth (Hughes and Farley) or by heritage (Dolan and the other seven), and none has been at a further remove from his Irish roots than a second generation.

There is a single exception, and just a half exception at that. Thomas J. OConnor, the father of Cardinal John J. OConnor (archbishop from 1984 until 2000) was proudly Irish and Catholic, but the cardinals mother, Dorothy Gumpel OConnor, a Catholic convert at age nineteen, was the daughter of German (Prussian, to be exact) Jews. In fact, her father was a rabbi. Apparently Cardinal OConnor was unaware of the fact, since it came to light only after his death. As the cardinals sister, Mary OConnor Ward-Donegan, said in 2014: That means my two brothers were Jewish, my sister was Jewish and I am Jewish. Of that I am very proud. Mrs. Ward-Donegan was referring to the matrilineal tradition in Judaism. She believes that her brother John, a tireless champion of Jews in New York and around the world, would have been very proud of his Jewish roots.

Since 1850, when the diocese of New York was elevated to archiepiscopal status, there have been thirty-two American presidents, forty New York governors, twelve popes, but just ten archbishops of New York. And (this is the second title clarification) we should make it clear here that this book is about those ten men, the ones who headed the archdiocesethe ordinaries, as they are known. We mention in passing some others who have held the rank of archbishop (the great Fulton J. Sheen, for example), and the first chapter traces the history of the New York diocese before 1850, but this books focus in on the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of those ten ordinaries: John Hughes, John McCloskey, Michael Corrigan, John Farley, Patrick Hayes, Francis Spellman, Terence Cooke, John OConnor, Edward Egan, and Timothy Dolan.

Not all of New Yorks archbishops have been headline makers, of course. Both Cardinal John McCloskey, the second archbishop, and Cardinal Edward Egan, the ninth, preferred to keep a lower profile than did, for instance, Archbishop Michael Corrigan, the third archbishop, or Cardinal OConnor, the eighth. To some extent, this has been a matter of personal style, but in other cases, the public profile of New Yorks Catholic leader has been determined by the issues he has been forced to address. War, poverty, nativism, education, anti-Catholicism, and, more recently, matters of faith and morals have made it necessary for even the most publicity-shy archbishops to restate Church teaching clearly and to confront those who oppose that teaching.

It is unlikely in the contemporary media environment that Cardinal Dolan, and the men who will succeed him, will ever again be able to use the single medium of print to communicate with the faithful. Throughout the history of the archdiocese, printed appeals from New Yorks ordinaries, often read aloud by priests from the pulpits of every New York church, have given clear explanations of Catholic doctrine, thus fulfilling one of the key responsibilities of an archbishop. Today, communication between Church officials and the people is carried on mostly via mass media, especially television, and the Internet, and this happens in an era of shortened attention spans, which, despite the potential for much greater exposure of an archbishops message, actually makes clarity in messaging more difficult. It is often the case that the message the media promote is an interpretation of what the archbishop has actually said, one crafted to appeal to constituencies (or the reporters or mediums view of what the Church should be), even to gin up the sort of controversies that lead to further stories. This is one of the great challenges the Church has faced in the era of the New Evangelization.

But messaging is only one aspect of an archbishops job. The media prefer to focus on any archbishops positions that affect political debates, but most of the clerics time is taken up in the management of Church affairs. Because these management matters are often of little interest to reporters, the stories reporters cover may make it seem to viewers and readers that archbishops are involved mostly in politics. An exceptionat least in New York mediais Cardinal Dolans recent decisions concerning the closing of parishes throughout the archdiocese, which became front-page news. But most of what Cardinal Dolan does on any given day is simply not fodder for media consumption.

As Reverend Thomas J. Reese, S.J., has written, Bishops actually spend very little of their time on public policy. They are concerned mostly with internal church matters in their own dioceses.

This is true, and yet even in earlier times the public profile of the archbishop of New York, his visibility, has made him not simply a force in the worlds media capital but a potential power broker as well. Writing in response to the appointment of Francis Joseph Spellman in 1939 (and using Manhattan to represent the whole archdiocese), the editor of the Catholic World noted:

New York is what it is reputed to be, a cosmos, a world on a narrow and not very long island...In a manner of speaking he [Spellman or any archbishop of New York] becomes the leader of the world, or at least of a world: and I hope I may say without undue exuberance that he has a greater opportunity to battle evil and to amplify good than any other one man except the Holy Father. There is no see in Christendom with such potentialities as New York.

Next page