THE INVENTION OF INTERNATIONAL ORDER

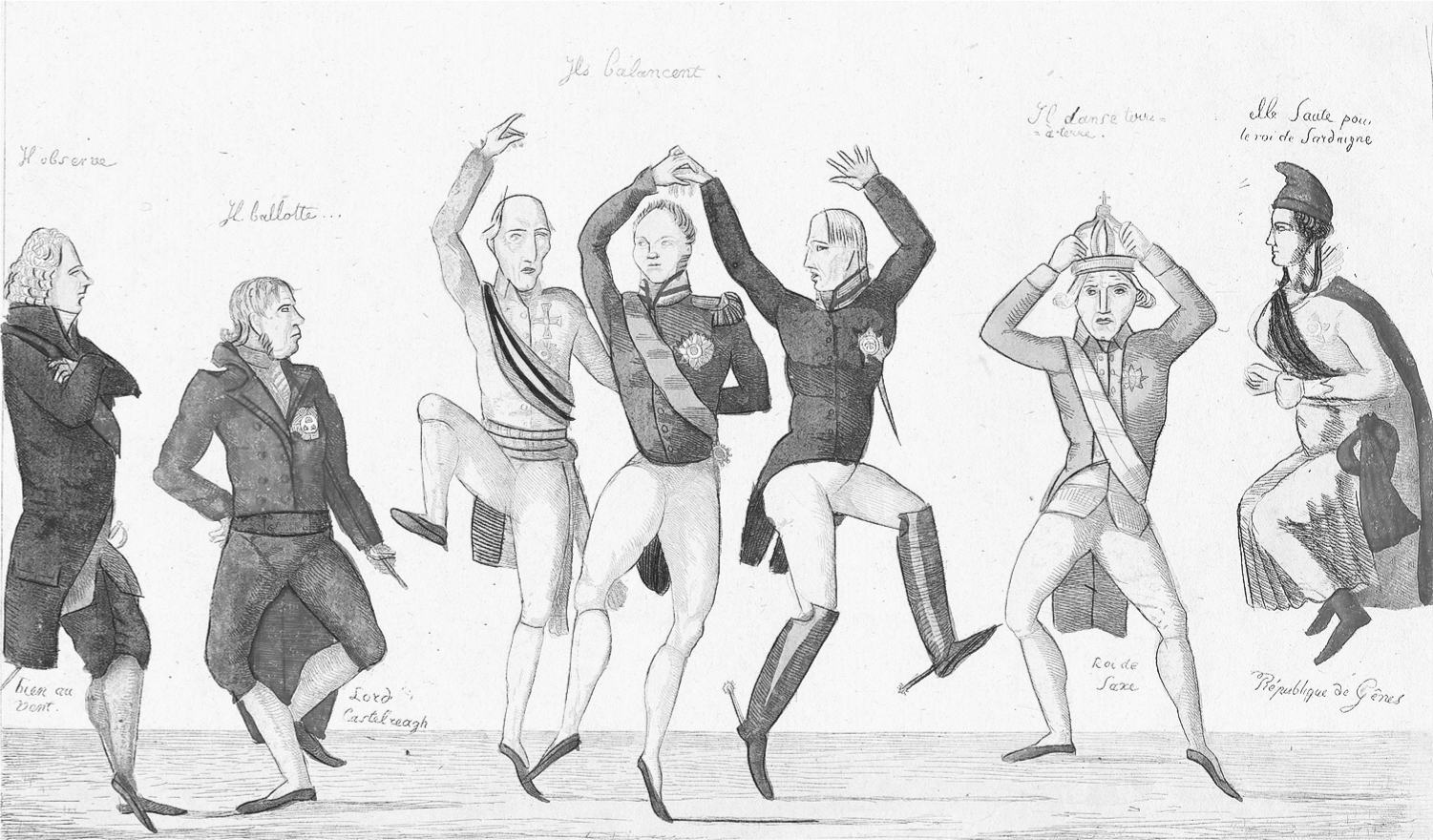

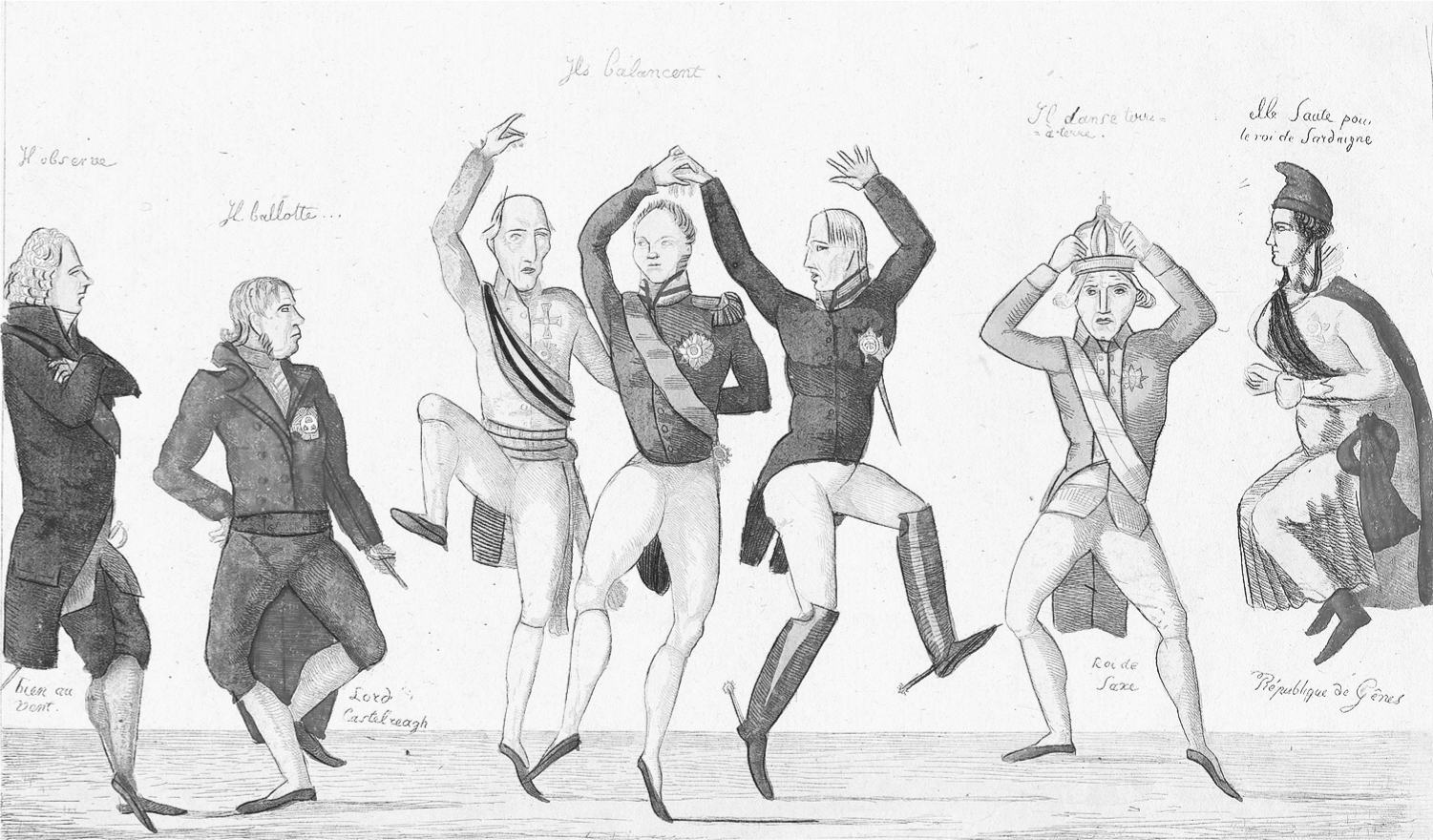

Forceval, Le Congrs, 1815. Engraving, 18.6 27.5 cm. Bibliothque nationale de France, Dpartement des Estampes et de la photographie.

The Invention of International Order

REMAKING EUROPE AFTER NAPOLEON

Glenda Sluga

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-20821-3

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-22679-8

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Priya Nelson, Thalia Leaf and Barbara Shi

Production Editorial: Jenny Wolkowicki

Jacket design: Layla Mac Rory

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Carmen Jimenez

Jacket art: Le Congrs, 1815. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. The Trustees of the British Museum

For Vida Cetin (19342020)

When we study history, it seems to me that we acquire the conviction that all major events lead towards the same goal of a world civilization. We see that, in every century, new peoples have been introduced to the benefits of social order and that war, despite all its disasters, has often extended the empire of enlightenment.

GERMAINE DE STAL, DE LA LITTRATURE

[The Vienna generation had learned] from bitter experience that war was revolution [and] that something else even more fundamental to the existence of ordered society as they knew it was vulnerable and could be overthrown: the existence of any international order at all, the very possibility of their states coexisting as independent members of a European family of nations.

PAUL W. SCHROEDER, THE TRANSFORMATION OF EUROPEAN POLITICS

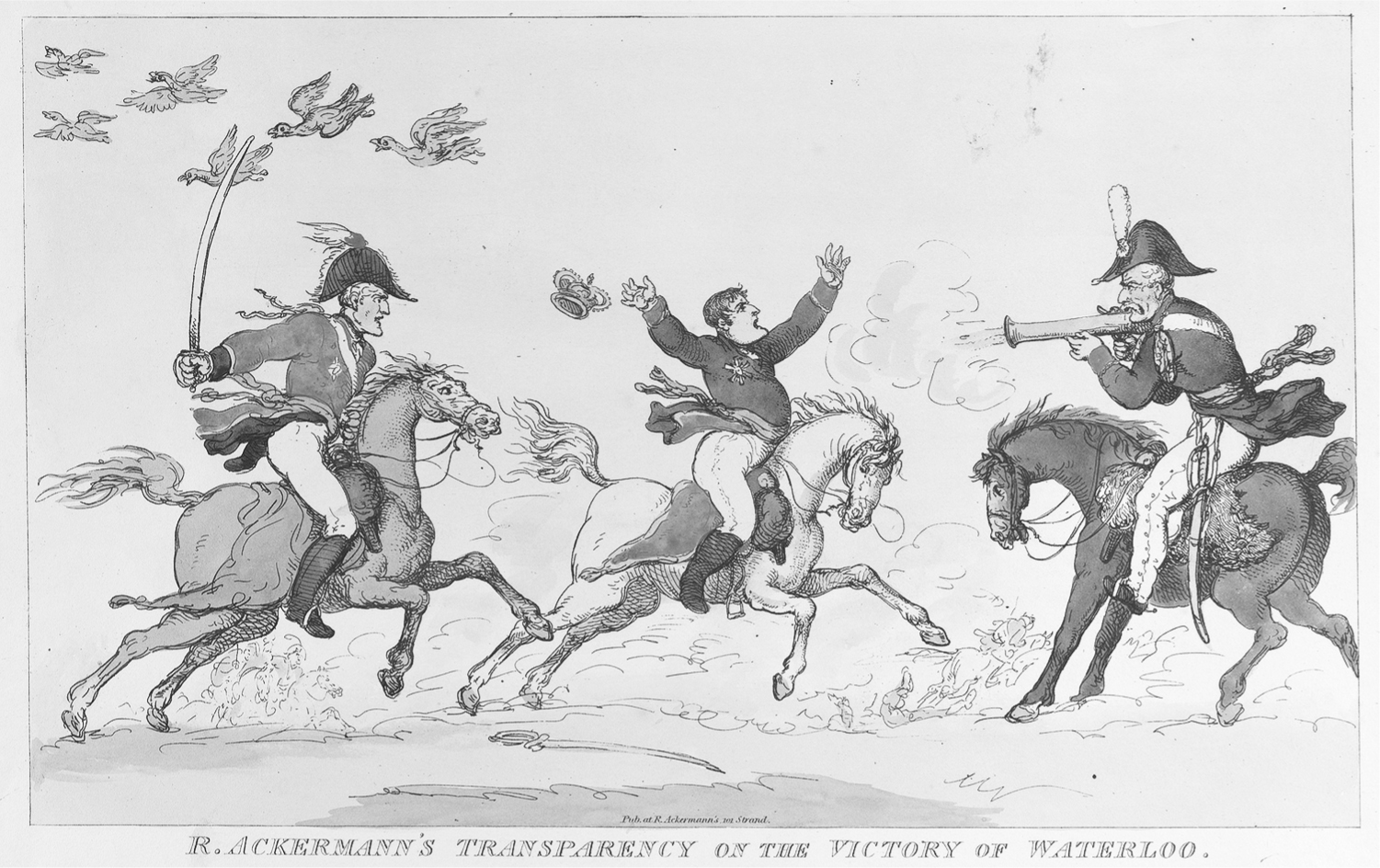

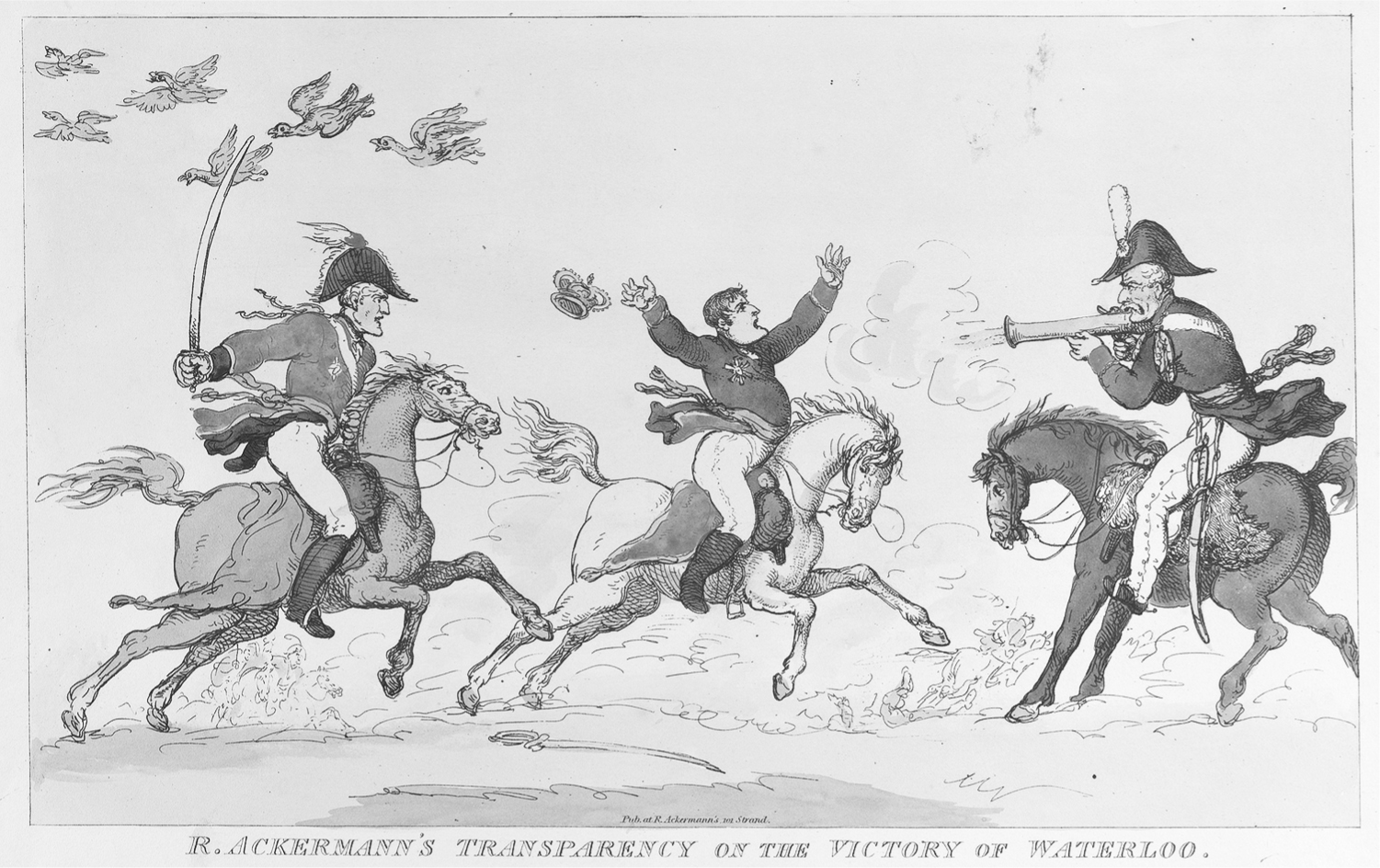

FIGURE 1. Thomas Rowlandson, R. Ackermanns Transparency on the Victory of Waterloo, 1 June 1815. Hand-colored etching, 22 33.8 cm. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

CONTENTS

- xi

- xiii

- 1

PREFACE

A HISTORIAN looking back at the early twenty-first century will find a world rife with predictions of the end of the international order. The nostalgia that tends to accompany these gloomy predictions looks to the end of World War II in 1945, when the United States and the U.S. dollar were globally ascendant. But the existing international order is the sum of much more than mid-twentieth-century alliances. At stake are at least two centuries of multilateral principles, practices, and expectations. The intention of this book is to return to the early nineteenth century as the origin of the conception of international order that shaped modern international politics.

In 1814, after decades of continental conflict, an alliance of European empires defeated French military expansionism and established the so-called Concert of Europe. At this definitive moment, the empires of Russia, Prussia, Britain, and Austria agreed to elevate cooperation between states in unprecedented ways. Their efforts annexed multilateralism to moral purpose, not least the idea of a permanent or durable peace; they deployed diplomacy, conferencing, and cross-border commerce, even free trade, as methods to secure that peace. As importantly, the diplomacy-focused contours of this international politics, from its committees to its salon-based sociability, drew the attention of a wider public whose opinions had begun to matter and who embraced the possibilities of the politics between states with enthusiasm. In the decades that followed, the combinations of new methods and new expectations became part of the history of the invention and reinvention of the parameters of international relations, with simultaneous invocations of humanity, on the one hand, and delineations of exclusive, consistently European, and hierarchical political authority, on the other. With the advantage of hindsight, this longer history helps us understand the extent of international thinking and ordering at stake in our own faltering international order: What counts as international politics? How might politics be organized? Who should or can participate, and to what end?

Over the last two centuries, since the end of the Napoleonic wars, fundamental changes have touched all dimensions of human existence. We have moved from horses to steam, to flying machines and virtual reality; from a Europe divided between a few empires and dynastic families to a system of nation-states; from salons and dueling to nuclear brinkmanship and war fought through artificial intelligence. Yet the fundamental elements of international order that still matter have deep practical and ideological roots in peacemaking policies and practices, as well as the politics that the promise of peace excited in early nineteenth-century Europe. When we consider the unprecedented existential threats the world faces nowsystemic collapse of societies under pressures of war, disease, and social and economic injustice, a planetary-level ecological crisissome might argue that historical lessons have their limits. But even a two-hundred-year-long history still matters, for getting our bearings and navigating the future, for its confirmation that peacemaking can be the mother of invention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN THE SUMMER OF 2013, I participated in a documentary about women at the 1814 Congress of Vienna, the infamous gathering that signaled the end of the Napoleonic wars and the beginning of a new international era of European politics. The documentary was the idea of a wonderfully enthusiastic filmmaker intent on giving legitimacy to women as political actors in that history. Her film team followed me to a remote villa in the Umbrian countryside where, in suitably ancien surrounds, I shared my stories of Germaine de Stal, Anna Eynard-Lullin, Rahel Varnhagen, and others. Not least, I remember they had forgotten the filter that would ensure my face was not a mess of aging shadows; we filmed anyway. A year later, the writer contacted me about the launch at the Austrian Foreign Ministry and Chancellery on Viennas Ballhausplatz, in the same rooms that had been the site of epoch-shifting political negotiations two hundred years earlier. If I felt some trepidation about the visual effects of the absent filter, it was soon overtaken by the news that production had been placed in the hands of a company less interested in the subtleties of gender politics. Indeed, the title of the documentary shown at the 2014 launchDiplomatic Affairs of the Mistresses of the Vienna Congress