The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1992 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1992

Paperback edition 1992

Printed in the United States of America

00 99 98 97 96 5 4 3

ISBN (paperback): 0-226-77983-1

ISBN-13 : 978-0-226-05098-0 (e-book)

Published with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Publications Fund of Yale University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Suleri, Sara.

The rhetoric of English India / Sara Suleri.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Indic literature (English)History and criticism. 2. Anglo-Indian literatureHistory and criticism. 3. English literatureIndic influences. 4. English languageIndiaRhetoric. 5. Imperialism in literature. 6. BritishIndiaHistory. 7. Colonies in literature. 8. India in literature. I. Title.

PR9484.3.S85 1992 91-13014

820.93254dc20 CIP

courtesy Field Museum of Natural History,

Neg. # A111654, Chicago.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984

THE RHETORIC OF ENGLISH INDIA

Sara Suleri

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

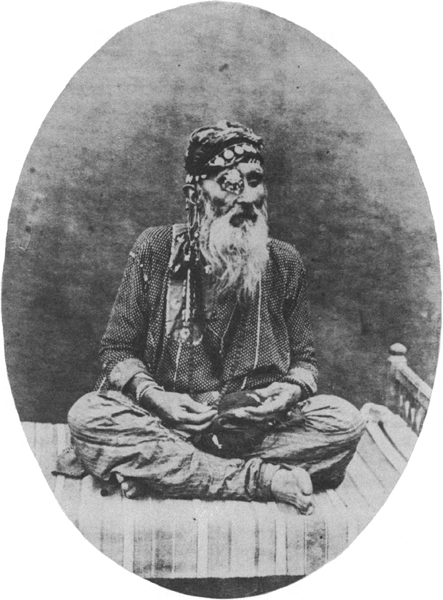

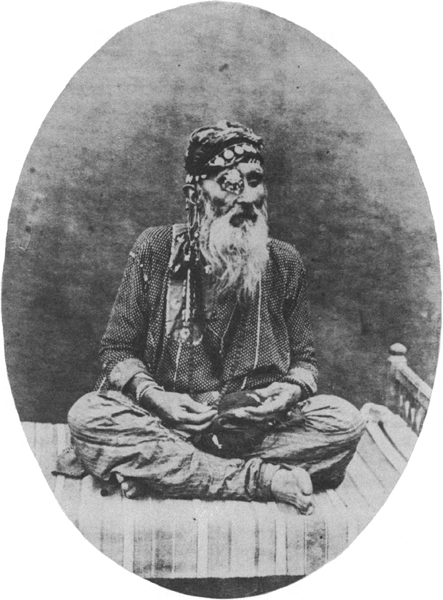

The Sodhees have in general an evil reputation for immorality, intoxication, and infanticide, the latter being justified by them on the ground that it is impossible to marry their female children into ordinary Sikh families.... The subject of the photograph resides at Lahore. He has lost an eye, which is covered by an ornament pendant from his turban; and it is a strange peculiarity of this person, that he dresses himself on all occasions in female apparel.

From The people of India (186875)

For my father

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK HAS RECEIVED MORE SUPPORT THAN I FEAR IT MAY DESERVE. MY FIRST thanks I must proffer to my students, whose energies have kept me buoyant through many a long hour of writing. While it would be impossible to list the friends and colleagues at Yale who have wittingly or unwittingly come to my intellectual rescue, I owe particular gratitude to timely comments on my writing by Michael Holquist, Patricia Meyer Spacks, Christopher Miller, David Bromwich, Akeel Bilgrami, and Peter Brooks. The editorial collective of the Yale Journal of Criticism deserves equal thanks for its enabling interest in the work of each of its editors. Furthermore, this work was both impelled and impeded by the constant encouragement of such friends as Dale Lasden, Nuzhat Ahmad, Jamie MacGuire, and Anita Sokolsky. My thanks to them.

I am grateful to Yale University for providing me with a Morse Fellowship to conduct research on this project, and to the Griswold grant that allowed me to travel to India and Pakistan. My research in both countries was greatly aided by Kum Kum Sangari, Sheherezade Alam, and Zarene Shafi.

Earlier segments of the chapters on V. S. Naipaul and Salman Rushdie have appeared in the Yale Journal of Criticism and the Yale Review: both journals must be thanked for their permission to reprint. The brief afterword to chapter 8 (p. 218, ) first appeared in Transition 51 (1991).

Finally, I am happy to acknowledge the imaginative patience of my editor, Alan Thomas, and his remarkable capacity to justify to me the expansive possibility of deadlines. His professional commitment to my writing has been nicely tempered by my siblings somewhat impatient refrain, Get it done. My one regret is that I did not get it done before Nuzhat Suleri could have taken pleasure in the texts reality. If on this earth, however, she would be the first to agree that my ultimate thanks should go to Fawzia Mustafa, whose astonishing friendship provides the periods for each sentence I may write.

The Rhetoric of English India

THIS WAS HOW IT HAPPENED; AND THE TRUTH IS ALSO AN ALLEGORY OF Empire, claims Kiplings narrator, as he opens with grim brevity the quasi tale of 1886, Naboth. Like much of the early writing that Kipling published in the Civil and Military Gazette of Lahore, the story itself represents a dangerously simple moment of cultural collision: situated on the cusp between the languages of journalism and fiction, its three pages record an occasion of colonial complicity that bears testimony to the dynamic of powerlessness underlying the telling of colonial stories. The colonialist as narrator carelessly throws a coin to the native beggar in his garden, as kings of the East have helped alien adventurers to the loss of their Kingdoms (p. 71). Naboth to the narrators Ahab, the beggar initiates an act of counter-colonialism, setting up a confectionery stall in the colonizers garden that profits with a surreal speed, growing from a trading post to a set of shops, and finally, into a brothel. When the narrator puts a violent end to this invasion of his role as invader, he offers the following commentary on colonialisms ambivalent relation to the anxiety of empire: Naboth is gone now, and his hut is ploughed into its native mud with sweetmeats instead of salt for a sign that the place is accursed. I have built a summer-house to overlook the end of the garden, and it is as a fort on my frontier from whence I guard my Empire. I know exactly how Ahab felt. He has been shamefully misrepresented in the Scriptures (p. 75).

Kiplings tale functions as a cautionary preamble to my present work, which both seeks location within the discourse of colonial cultural studies and attempts to question some of the governing assumptions of that discursive field. While the representation of otherness has long been acknowledged as one of the most culturally vexing idioms to read, contemporary interpretations of alterity are increasingly victims of their own apprehension of such vexation. Even as the other is privileged in all its pluralities, in all its alternative histories, its concept-function remains too embedded in a theoretical duality of margin to center ultimately to allow the cultural decentering that such critical attention surely desires. As the allegory of Naboth suggests, the story of colonial encounter is in itself a radically decentering narrative that is impelled to realign with violence any static binarism between colonizer and colonized. It calls to be read as an enactment of a cultural unrecognizability as to what may constitute the marginal or the central: rather than reify the differences between Ahab and Naboth, Kipling illustrates both the pitiless congruence in their economy of desire and the ensuing terror that must serve as the narratives interpretive model.

Such terror suggests the precarious vulnerability of cultural boundaries in the context of colonial exchange. In historical terms, colonialism precludes the concept of exchange by granting to the idea of power a greater literalism than it deserves. The telling of colonial and postcolonial stories, however, demands a more naked relation to the ambivalence represented by the greater mobility of disempowerment. To tell the history of another is to be pressed against the limits of ones ownthus culture learns that terror has a local habitation and a name. While Ahab may need to identify a Naboth as a discrete cultural entity, finally he knows that his encounter with the other of culture is only self-reflexive: in the articulation of Naboths secular story, Ahab is caught up against a more overwhelming narrative that forces him to know he has been shamefully misrepresented by the sacred tales of his own culture. The allegorization of empire, in other words, can only take shape in an act of narration that is profoundly suspicious of the epistemological and ethical validity of allegory, suggesting that the term culturemore particularly, other culturesis possessed of an intransigence that belies exemplification. Instead, the story of culture eschews the formal category of allegory to become a painstaking study of how the idioms of ignorance and terror construct a mutual narrative of complicities. While the allegory of empire will always have recourse to the supreme fiction of Conrads Marlow, or the belief that what redeems it is the idea alone, its heart of darkness must incessantly acknowledge the horror attendant on each act of cultural articulation that demonstrates how Ahab tells Naboths story in order to know himself.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984