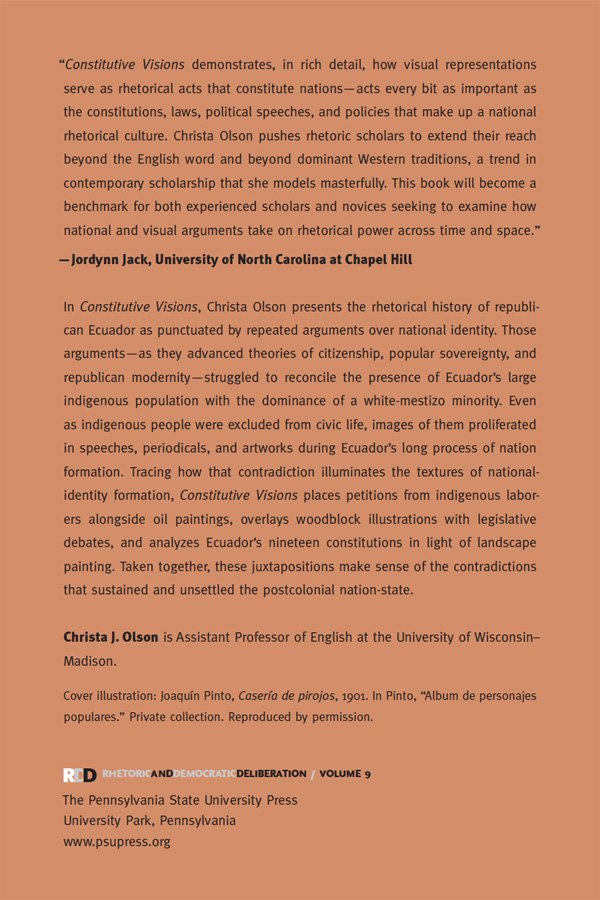

CONSTITUTIVE VISIONS

EDITED BY CHERYL GLENN AND J. MICHAEL HOGAN

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

Editorial Board:

Robert Asen (University of Wisconsin, Madison)

Debra Hawhee (The Pennsylvania State University)

Peter Levine (Tufts University)

Steven J. Mailloux (University of California, Irvine)

Krista Ratcliffe (Marquette University)

Karen Tracy (University of Colorado, Boulder)

Kirt Wilson (The Pennsylvania State University)

David Zarefsky (Northwestern University)

Rhetoric and Democratic Deliberation is a series of groundbreaking monographs and edited volumes focusing on the character and quality of public discourse in politics and culture. It is sponsored by the Center for Democratic Deliberation, an interdisciplinary center for research, teaching, and outreach on issues of rhetoric, civic engagement, and public deliberation.

A complete list of books in this series is located at the back of this volume.

CONSTITUTIVE VISIONS

INDIGENEITY AND COMMONPLACES OF NATIONAL

IDENTITY IN REPUBLICAN ECUADOR

CHRISTA J. OLSON

The Pennsylvania State University Press | University Park, Pennsylvania

Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-271-06198-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-271-06199-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Copyright 2014 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member

of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University

Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated

stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American

National Standard for Information Sciences

Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Material,

ANSI Z39.481992.

For ANNA, and our next adventure

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

MAP

FIGURES

PREFACE: THE PRECARIOUS POLITICS OF GOING THERE

How Ecuadorean journalists are teaching the Indians to read and write and like it. So begins The articleabout Indians, literacy, and national lifenot only gives a glimpse of ethnopolitics in its own moment but also offers an instructive opening anecdote for this early twenty-first-century book about rhetoric, visual culture, and indigeneity.

Alphabet tells the story of a literacy project run in the Quito area by the Ecuadorian Unin Nacional de Periodistas (UNP, National Journalists Union). The first page of the article introduces us to its main characters: pitiable, malleable Indians and initially skeptical but quickly trained teachers. It gives as well a brief profile of one indigenous student, Rafael Llumiquinga, whom the strength of literacy moved from unwashed and unpleasantly aromatic into cleanliness and confidence. Utterly changed, the article notes, Llumiquinga wrote to the local paper, saying that at last he felt like a man (27).

After praising the work done by the UNP, Alphabet next describes a visit by literacy researchers from the United States sent to the project by the U.S. Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA) and the Walt Disney Company. According to Alphabet, the motion pictures those visitors brought to encourage literacy and improve hygiene were almost too successful. They drew new students to the project in droves, overflowing rooms and lending a powerful new efficiency to the labor of teaching and learning (28).

As much as it celebrates the outcomes of the literacy projects discussedboth the pen-and-paper strategies of the UNP and the motion-picture efforts of the CIAAWalt Disney expeditionAlphabet is also a celebration of influential visuality. The author, Miguel Albornoz, both praises the visual learning techniques employed in the program and emphasizes visual elements in his effort to draw in readers. He shows, in both areas, a significant faith in the power of seeing, and seeing anew. For Albornoz, the quality of literacy acquisition in the program is visible and tightly linked to an image-based taxonomy. In his descriptions, indigeneity and modernity are visually marked poles existing in generative tension, both diametrically opposed and inextricably connected. He pictures illiterate Indians as dirty and ponchoclad, clumsily premodern in the shape of their hands and the set of their bodies. Yet they are eager for access to development and its bright lights, colors, and straight lines. In response, literate (nonindigenous) teachers provide printed flashcards and cartoon filmstrips that teach hygiene and modern skills. Accessing text and image transforms those miserable, mudcaked Indians into clean, bright-eyed, and trembling protocitizens. From ponchos, dirty fingernails, and crowded rooms to filmstrips, electric lights, and shining faces, acquiring literacy (and modernity) proves a thoroughly visual affair in Albornozs hands.

Published first in the U.S. government periodical the Inter-American and then four years later in an Ecuadorian travel magazine, Ecuador, Alphabet had two different audiences. The Inter-American, the official organ of the CIAA, was distributed to U.S. State Department affiliates throughout the Americas. In Ecuador it would have been read by U.S. expatriates, members of the U.S. diplomatic corps, and Ecuadorians affiliated with those groups. The short-lived tourism magazine Ecuador, for its part, carried an appealing image of Ecuador to potential tourists both within the country and throughout the Americas. Its articles in Spanish and English situated Ecuador as a picturesque, culture-rich, and accessible nation. Both versions of the article, then, reached outward. They offered their story of literacy learning and national progress to an audience indirectly involved in the UNPs project yet, in many cases, intimately connected to it by their shared goals of modern development.

That sharp anxiety over modernity (and its lack) consumed both Ecuadorian political elites and the larger inter-American politics of development in the mid-twentieth century. In response, they launched a full-spectrum assault on the secondary signs of lingering rusticity, a status embodied particularly by indigenous peoples. Alphabet, in other words, resonates topically with other Ecuadorian documents of its era. It resonates as well in its form: oriented primarily in textual termsliteracy rates and economic statistics, political projects and historical analysesit relies heavily on the shaping force of seeing to spark identification and generate movement. The visual link that Albornoz makes between indigeneity and national development in his article was not, in other words, unusual. Yet his articles faith in the power of visionto change Indians and inspire readersoffers a concise representative anecdote for the ways that seeing indigeneity and seeing national identity have long run parallel in Ecuadorian civic life.

Using artifacts such as Alphabet in the Andes, this book traces textual and visual arguments about the nation threaded through more than a hundred years of Ecuadorian history. It takes up the specific example of Ecuador because that country has a long, rich, and well-documented history of explicit nation making and has consistently relied on the force of vision to carry that nation making forward. Like Alphabet, in other words, Ecuador offers an evocative representative anecdote for the rhetorical intersections of visuality and nationalism. Giving close attention to the constitutive force of vision as demonstrated so powerfully by the Ecuadorian example, this study unravels the multivalent nature of nationalism and the ways its shaping, matter-making influence extends across representative forms.