THE LONG HANGOVER

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Shaun Walker 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190659240

eISBN 9780190659264

CONTENTS

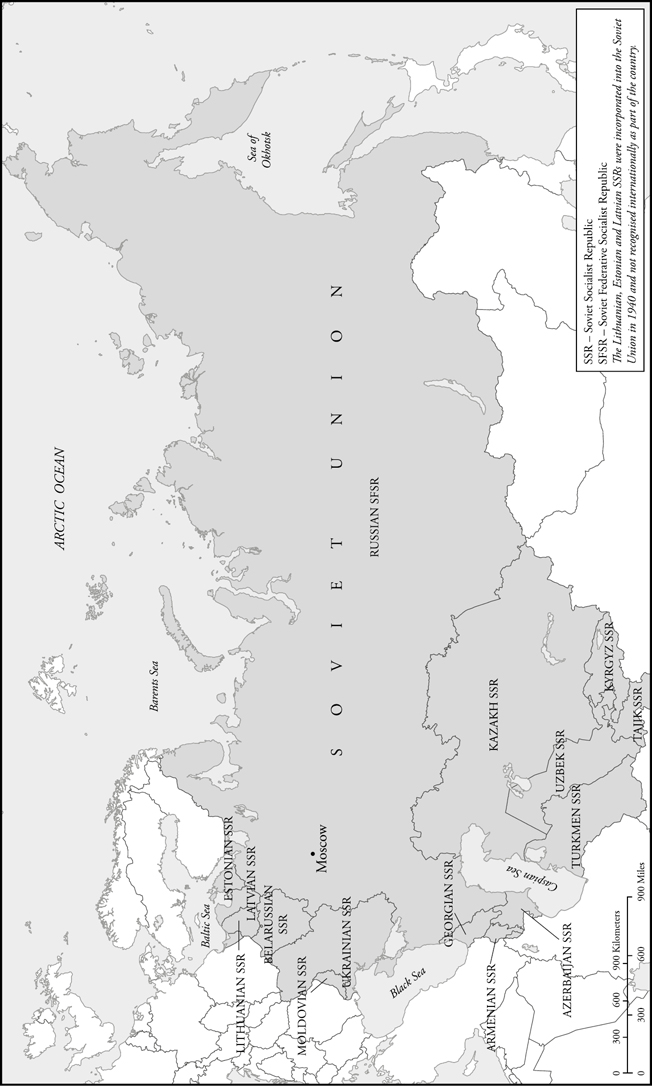

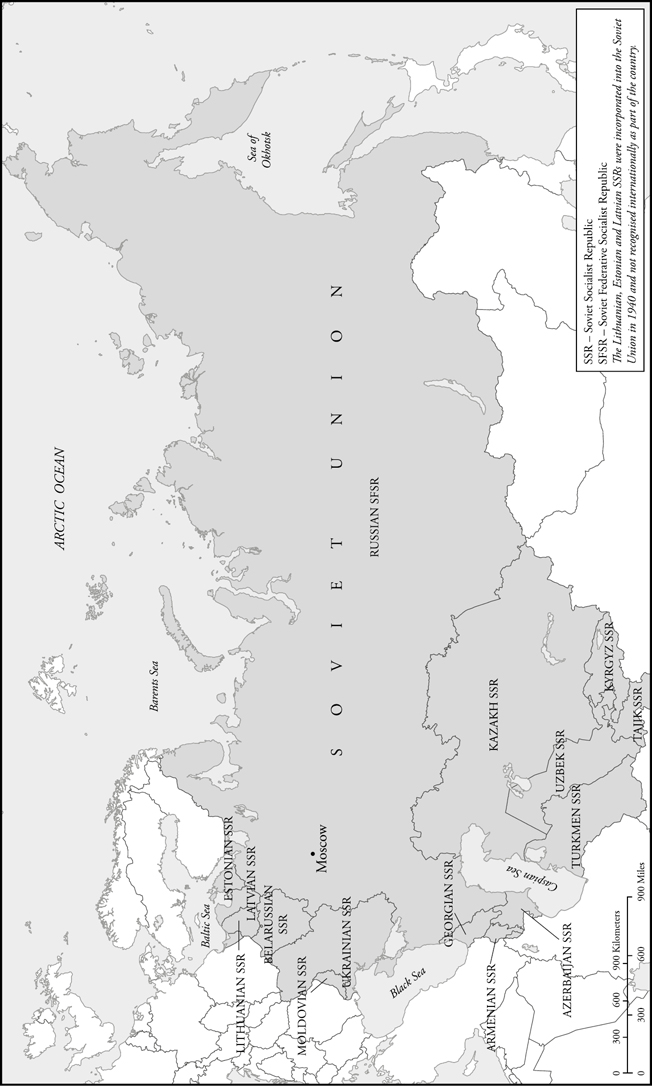

Map of the Soviet Union

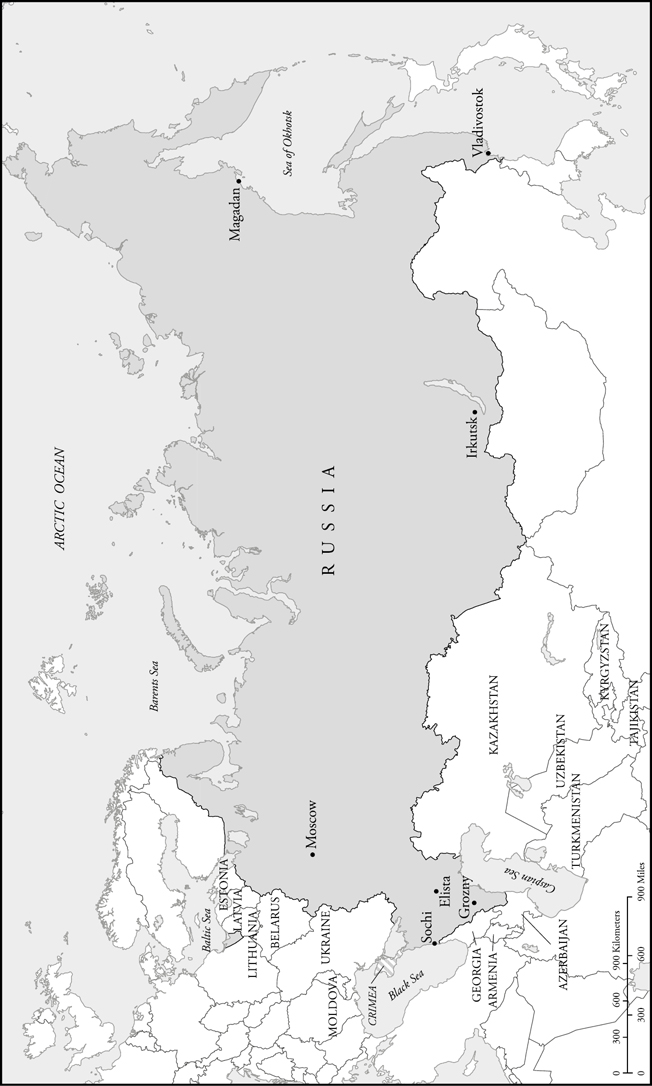

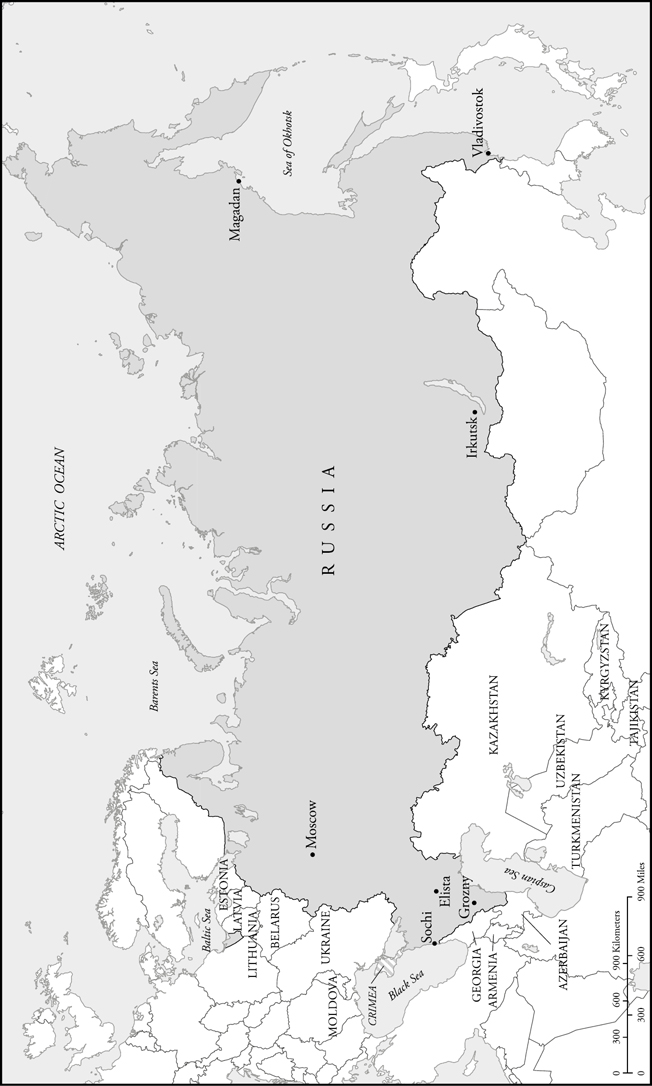

Map of Russia

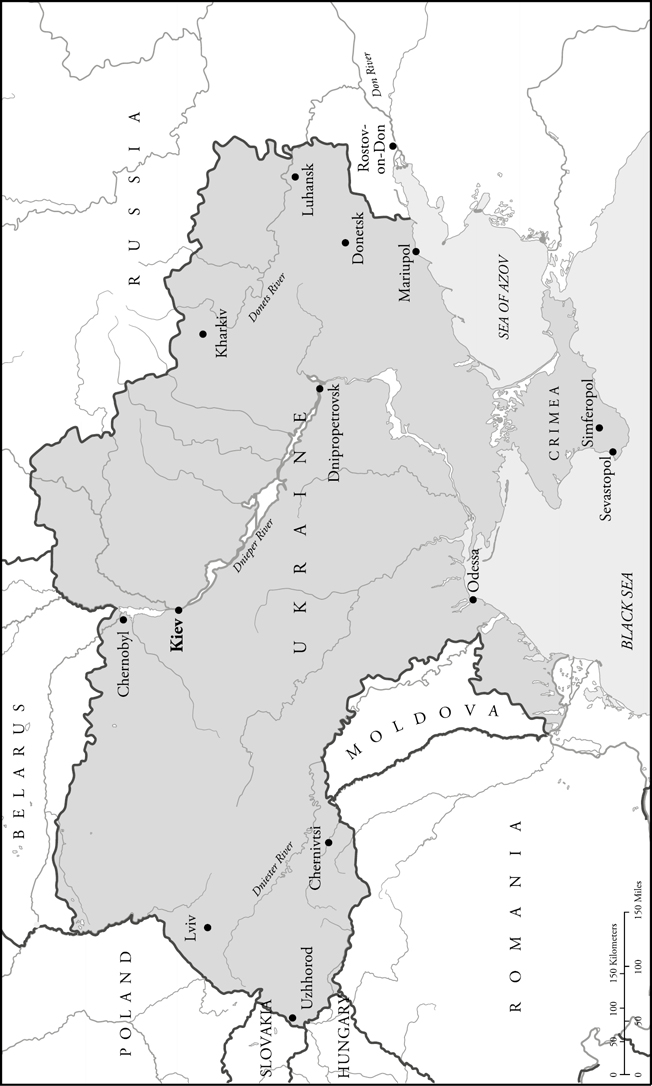

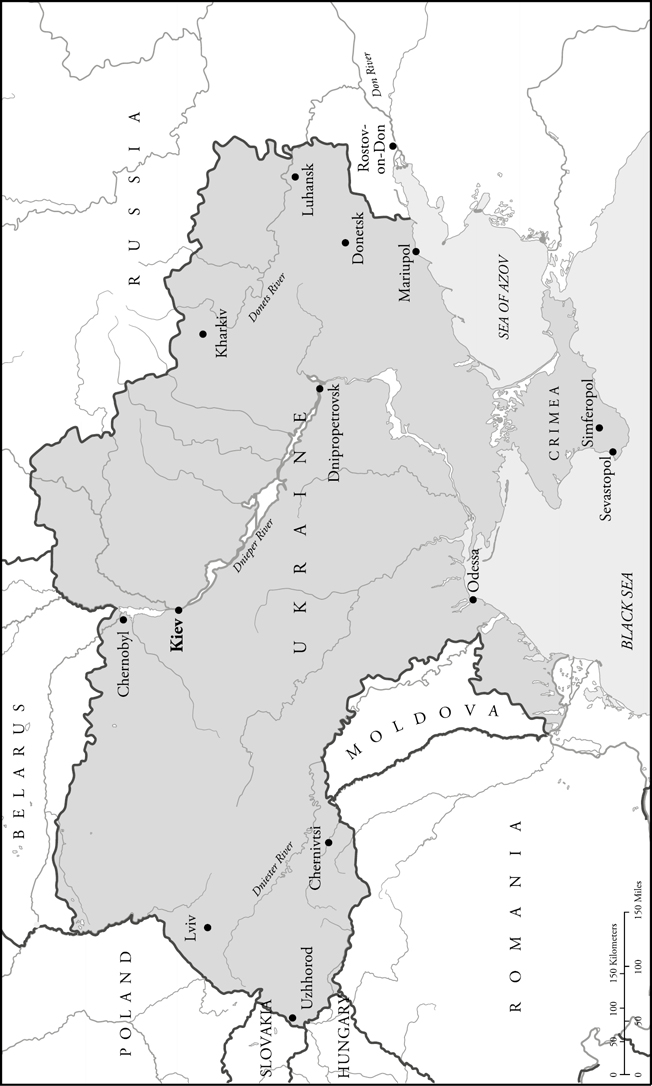

Map of Ukraine

October 2014, Torez, rebel-controlled eastern Ukraine

There had been an autumn chill in the air for a few days, and even inside the seized secret police headquarters, it was cold. The Romanian did not seem to notice the temperature, apparently comfortable in his light military jacket and a single, fingerless leather glove. But he clocked me shivering, and declared it unacceptable that the towns heating system had not yet come on. He had been to the power plant the previous day, he said, and laid down an ultimatum. They had a week to get things sorted or he would have the management shot for sabotage.

This might have been taken for bravado, were it not for the fact that the Romanian had organized two public executions in the preceding weeks. Most recently, a young man in his twenties had been caught looting by some of the Romanians men, and sentenced to the ultimate punishment. He thought it was a joke until the last minute, the Romanian said, puffing his way through the latest in a steady stream of cigarettes held in his ungloved hand.

The young man was executed by a bullet to the back of the head, outside the shop from which he had stolen. A crowd of locals gathered on the street to watch.

Public executions seemed a little out of place in twenty-first-century Europe, I ventured. The Romanian shrugged. Nobody blames a surgeon for the fact they remove tumours from the body with a scalpel. That is what we are doing here, with this society.

Despite the name, he was very much Russian; the Romanian was merely his pozyvnoi, a nom de guerre chosen because one branch of his family had roots in Romania. All the fighters I met during the war in eastern Ukraine had a pozyvnoi. There was the Amp (a former electrician), the Ramone (they were his favourite band), and the Monk (hed never cheated on his wife).

With their silly names, they often seemed like boys playing at war, but the Romanian was one of the serious ones. He radiated intensity, and had a clipped, military brusqueness when he spoke that bordered on disdain. Nevertheless, it was clear he enjoyed having an audience. He had griped repeatedly when our interview was set up that he did not have time to waste chattering with journalists. But when I arrived, he proceeded to talk about his fiefdom for three hours with little interruption, spraying literary and biblical references, ranging from the novels of Stendhal to obscure conspiracy websites about the Bilderberg Group. Tall and lean, with closely cropped greying hair and a neat, clipped moustache, he sat at the head of a long table, drinking over-brewed tea and ashing his cigarettes into a rusting old tuna tin. The walls were bare save for peeling light-blue paint.

The building had previously been the headquarters of the SBU, the Ukrainian security services, in the grimy mining town of Torez. Now, it was a heavily fortified base, controlled by the Russia-backed militias of the Donetsk Peoples Republic, a lawless quasi-state that had come into existence a few months previously.

A retired Russian military officer, the Romanian now held the official title of Head of Counterintelligence for the Ministry of State Security of the Donetsk Peoples Republic. In practice, this gave him license to act as a kind of vigilante ombudsman. A blonde woman, with gold hoop earrings, an elaborate manicure, and a combat jacket lined with faux fur, periodically entered the room to hand him sheets of paper, appeals from locals about looted property, or other grievances linked to rebel forces behaving badly.

He was trying to get to the bottom of one case of a local farmer, whose only cow had been pilfered by rebel soldiers. He had jailed several rebels for theft. The two public executions for looting were justified, he said, because only the lowest form of humanity would steal the few provisions remaining in the town. In order to live by the laws of the New Testament, first we must live by the laws of the Old Testament; an eye for eye. If the people behave like animals, we will treat them like animals.

This was the Romanians sixth war. The first had been the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, soon after he signed up. He became an officer in the Soviet and Russian armies, and later in an interior ministry special forces unit. There was no way of verifying his claims; he never even told me his real name. But I doubted he was lying.

Having been through the blood, mud, and brutality of both Chechen wars during the 1990s, he left the army. Afterwards, he tried his hand at civilian life, setting up a small construction company in Moscow. It was not a success, and he ended up working on the building sites himself to make a living.

The Romanian did not like corruption; his eyes sparkled with fury whenever he brought the subject up, which was often. If he had his way, he would have all the corrupt officials shot. Joseph Stalin had been right, he said; there may have been repression back then, but the country developed, and progressed, and that was the main thing.

Giving a bribe makes you feel like a gay. Its like being raped. This repulsive man standing in front of you with a leering smile and his hand open. Its disgusting. I never gave a single bribe when I was working in construction. He continued, pensively, after a pause: Thats probably why nothing ever worked out for me.