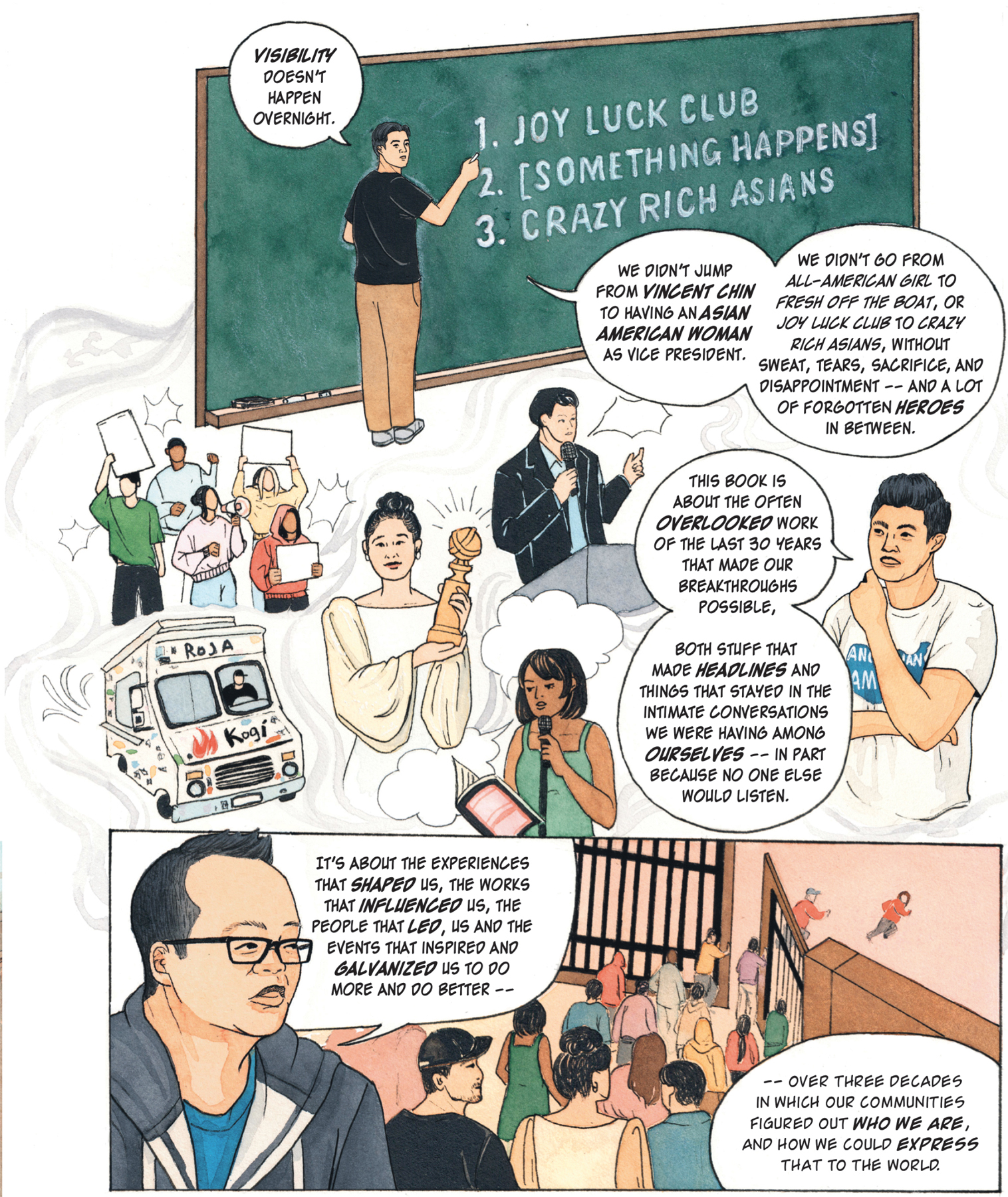

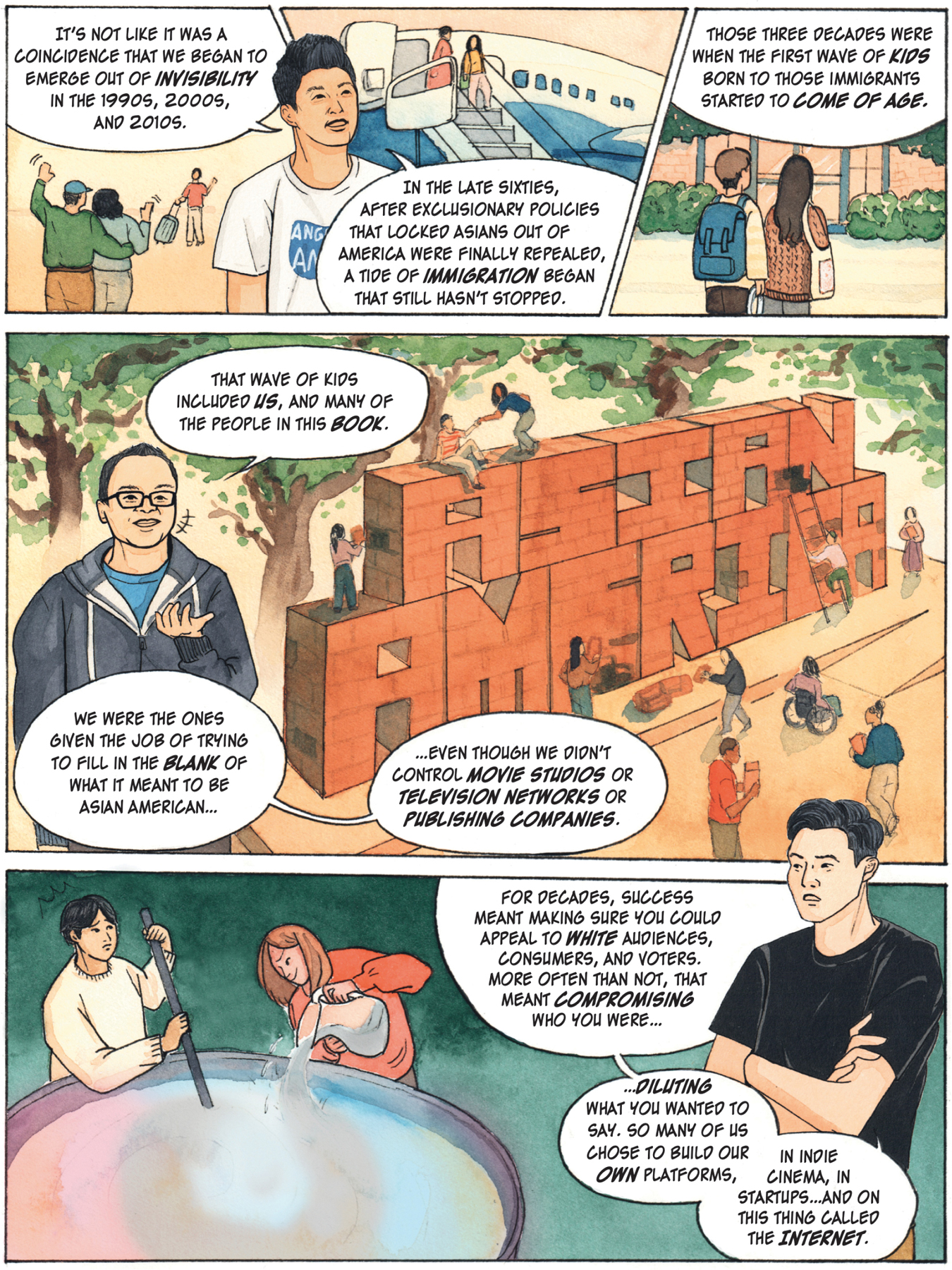

Contents

Guide

This book is dedicated to the ones who come next

Contents

STORY: JEFF YANG, PHIL YU, & PHILIP WANGART: KRISTAN LAI

WHERE DO WE begin? Or rather, when did we begin?

If you go by the history books, Asians have been in America since the 19th century, when Chinese immigrants toiled to build the infrastructure of Americas manifest destiny and fed the hungry bellies of goldstruck prospectors (and, after hours, took a turn at panning the glittering streams of California themselves).

If you go by the records that never seem to make it into textbooks, Asians have been in America since Filipino slaves jumped ship from Spanish galleons in Louisiana in the 1760s, where they built secret villages in the swamplands, hid from their kidnappers, fished to survive, and eventually, were recruited to defend a young America from a new British invasion in 1812.

If you crawl through the weird fringes of antiquarianism, youll find people who claim that a Chinese admiral landed his fleet of ships on the East Coast of the United States in 1421; that Japanese fishermen discovered America in the 13th century; that wandering Buddhist monks floated to a place called FusangCalifornia, maybe!in AD 499. And if you dive down into evolutionary anthropology, youll probably read about the Bering land bridge, crossed by ancient Asian migrants who trekked over from Siberia some 16,000 years ago and spread out all across whats now America.

But none of these moments, real or fake, really answer the question of when Asian America began... because none of the protagonists in these journeys ever thought of themselves as Asian. After all, Asia is a huge land mass, made up of wildly disparate states, most of whom have spent centuries trying hard to kill each other, or alternatively, trying hard to resist killing each other. Its difficult to imagine that these remarkably different peoples might choose to identify as a collective groupwhich makes the term Asian meaningless. In Asia, anyway.

Inventing Asian America

But this is America. And in America, not only does Asian mean something, we can pinpoint when that meaning came into being, and where: in May 1968, in the apartment of two grad students, Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee, at 2005 Hearst Avenue in Berkeley, California.

During the late Sixties, UC Berkeley and other San Francisco Bay Area universities bubbled with activist activity, carbon-charged by the fight for civil rights, the rise of the Black Power Movement, and growing outrage over the war in Vietnam. Ichioka and Gee recognized that the absence of a common banner under which to rally made activists of Asian descent invisible. They decided it was time to found an organization to unify, amplify, and uplift these voicesto allow them to stand side by side and shoulder to shoulder with Black, Chicano, and Native liberation movements. But what would this group be called?

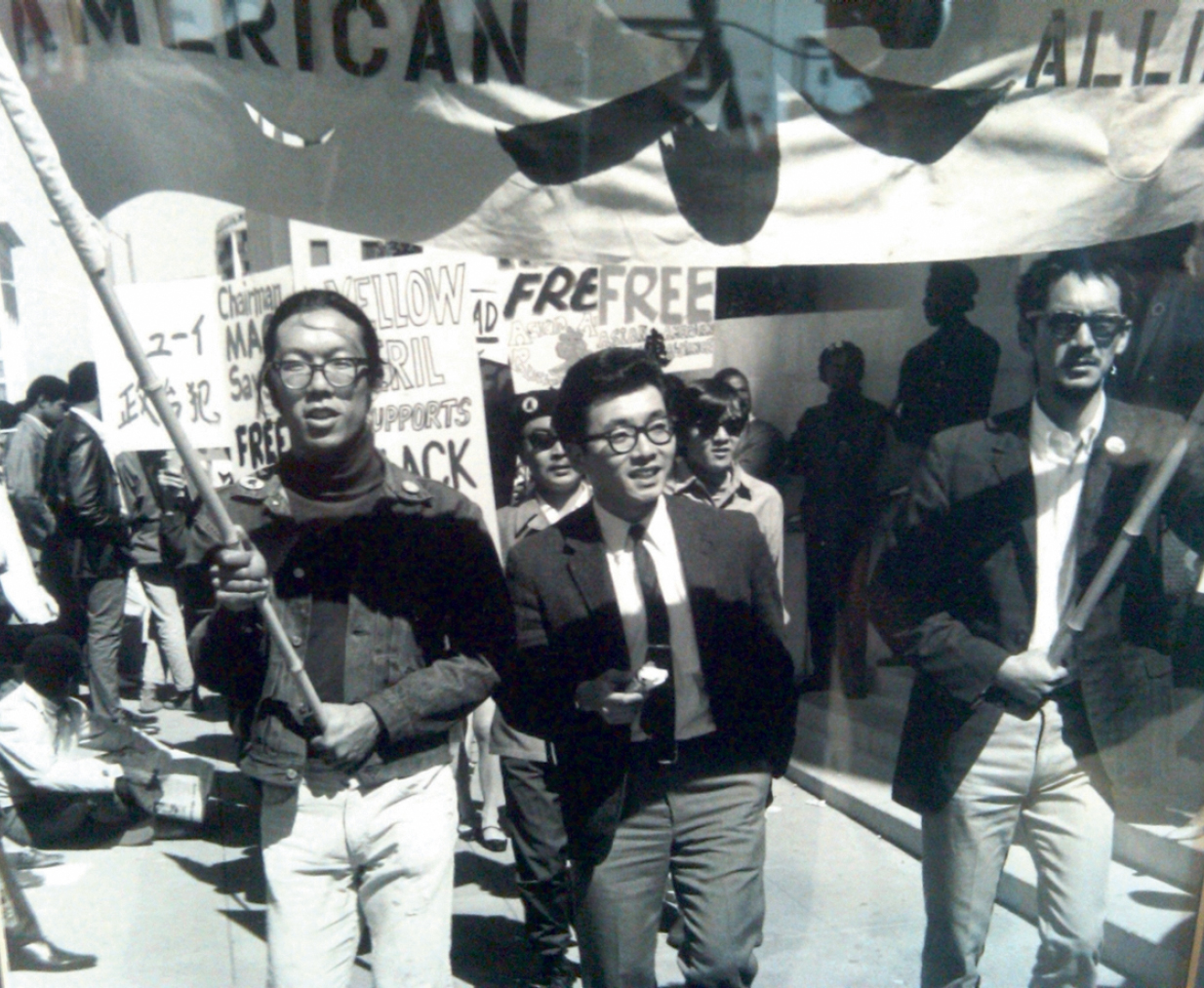

AAPAs Victor Ichioka, Phil Nakamura and Yuji Ichioka march in support of Black Panther Huey Newton (courtesy: AAPA Archive Project)

Courtesy of the Asian American Studies Center

The answer emerged from the first organizing meeting that took place in the living room of Ichioka and Gees apartment, after theyd made cold calls to every activist they could find who had a Chinese, Japanese, or other Oriental-sounding surname. The half-dozen students who gathered to plan the nascent groups June 2 kickoffIchioka, Gee, Ichiokas brother Victor, Vicci Wong, Floyd Huen, and Richard Aokidubbed themselves the Asian-American Political Alliance, coining Asian-American in emulation of their Afro-American fellows in the fight, a point that Ichioka made abundantly clear in a statement that stands as something of a manifesto: Asian-Americans have been, and still are, used politically to the detriment of oppressed minorities. AAPA will break the silence [of the Asian-American community] on the issues now confronting America... a nation which shows every evidence of liquidating Black people, and is waging the politically and morally insane war in Vietnam. We must redefine our relationship to the Black, Mexican-American and Indian liberation movements [because] all existing organizations in our community are too committed to the status quo.

Under the freshly painted AAPA banner, a membership that included Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino Americans organized and marched for Third World Liberation, for civil rights, for worker unionization, and for the release of Black Panther leader Huey P. Newtonrallies that marked the first recorded usage of the term Asian-American in a public context.

This wasnt the first time Asians of different ethnicities had been classified as a single group: at various times before this moment, wed been lumped together as Mongoloids, Orientals, Asiatics, and a variety of interchangeable slurs related to the color of our skin, the shape of our eyes, and the things we eat (or are alleged to eat).

But it did represent the first time Asians had embraced a sense of common identity for ourselves, by choice, and the discovery of a budding power in that choice. As charter member Huen later wrote, this invention of Asian America represented the learnings of a racially common group of American youth who were tired of being labeled meek and passive, and wanted to self-define like other groups. Vicci Wong, another founding member, put it even more simply: I went into AAPA Oriental, and left as an Asian American.

It wasnt a coincidence that the impetus for taking this first step together was politics. In majority-rules America, size matters, and grouping together into larger coalitions is a necessity to be seen, to be heard, and to get anything done. As Ichioka told Yn L Espiritu in an interview for her book Asian American Panethnicity, There were so many Asians out there [but] everyone was lost in the larger rally. We figured that if we rallied behind our own banner, behind an Asian American banner, we would have an effect on the larger public.

They certainly did. Though AAPA was only around for a few short years, in that time it was a visible and powerful presence as part of the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition with African American, Mexican American, and Native American groups. The Front rocked Bay Area campuses with four months of demonstrations, student strikes, and acts of resistance that ultimately led then-governor Ronald Reagan to send in the National Guard. AAPA chapters sprang up at other colleges across California and then beyond, from New York to Hawaiifighting, like their Berkeley flagship, for social justice, progressive change, and inclusion and representation for Asian Americans and other underrepresented groups.

But the biggest and most important legacy of the Alliance was, of course, the concept of Asian America itself. After taking root on college campuses, use of the term Asian American spread with shocking speed across academia, media, and business. By 1971, it had already reached government, with then- congressman Glenn Anderson, a Democrat from California, proposing the creation of a Cabinet Committee for Asian-American Affairs in a bill called the Asian-American Affairs Act (HR 12208) that would have the power to advise and direct Federal agencies for assuring that Federal programs are providing appropriate assistance for Asian-Americans. Additionally, the bill provides for the investigation of possible discriminatory practices against Asian-Americans.