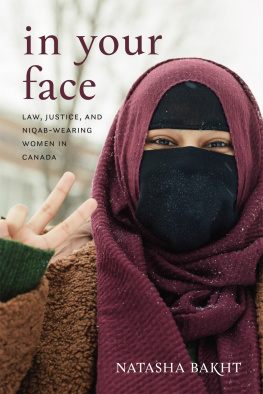

in your face

In Your Face Delve Books, an imprint of Irwin Law, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), 56 Wellesley St W, Suite 320, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S3.

Published in 2020 by

Irwin Law Inc

Suite 206, 14 Duncan Street

Toronto, ON M5H 3G8

www.irwinlaw.com

ISBN (print): 978-1-55221-549-4 | e-book ISBN (PDF): 978-1-55221-550-0 | e-book ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-55221-596-8

Cover photo of Aima Warriach by Charlotte Bibby

Author photo by Michael Slobodian

Cover and interior design by Heather Raven

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: In your face: law, justice, and niqab-wearing women in Canada / Natasha Bakht.

Names: Bakht, Natasha, author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200360124 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200360140 |

ISBN 9781552215494 (softcover) | ISBN 9781552215500 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Islamic clothing and dress Law and legislation Canada. |

LCSH: Clothing and dress Law and legislation Canada. | LCSH: Muslim women Legal status, laws, etc. Canada. | LCSH: Freedom of religion Canada. | LCSH: Muslim women Canada Social conditions.

Classification: LCC KE4430 .B34 2020 | LCC KF44383.C52 B34 2020 kfmod | DDC

342.7108/5297dc23

DEDICATION

To my parents, who taught me the value of respecting and welcoming difference.

Foreword

THIS IS A REMARKABLE book that should be read by everyone who has opinions on the wearing of the niqab (the full-face veil) and everyone who is still wondering what position to take. Few non-Muslim Canadians know much about the beliefs and traditions that underlie the niqab, yet this has not stopped most of us from adopting strong perspectives. Discussions about the niqab have a tendency to veer into hot disputes. Politicians, scholars, professors, judges, and media pundits have all grappled publicly with the question. Within my own circles of feminist thinkers and activists, there is widespread disagreement. Perspectives range from fervent criticism of garments perceived as sexist symbols of a patriarchal religion, to solid support for Muslim womens spiritual choices. Rarely is there sufficient space for careful reflection and analysis.

Natasha Bakht is a brilliant law and society scholar whom I have known for over twenty years, during which she has established herself as a first-class researcher, distinguished teacher, and highly effective advocate. She is the Shirley Greenberg Chair for Women and the Legal Profession at the University of Ottawas Faculty of Law, where she specializes in the intersection of religious freedom and womens equality. Although she does not choose to wear the niqab herself, Bakht has consistently taken a principled stand in favour of womens right to do so. She describes her background as being nurtured within an immigrant community of mixed cultural and religious heritage. Despite growing up in a Canada that defines itself as a multicultural society, Bakht has accurately noted the pervasive racial, ethnic, and gender discrimination that continues to disrupt our aspirations toward substantive equality. Concerned about the injury being inflicted upon vulnerable niqab-wearing women, she embarked upon the research that has resulted in this important book.

Natasha Bakht chose to speak directly with members of this minority group, to document womens own beliefs and experiences. For those of us who do not know niqab-wearers personally, or do not feel able to ask niqab-wearers questions about why they choose to wear the garment, this book is a source of rich qualitative information. Readers will find that it shifts discussions about the niqab to refocus upon the perspective of the wearer. This provides useful insights that counter misinformation disseminated in our heated and acrimonious debates.

In Your Face does not shy away from itemizing and probing the arguments put forth by those who oppose the niqab. Using an intersectional feminist framework, it examines the most popular claims advanced to forbid women from wearing the niqab in public spaces. It analyzes the arguments against allowing niqabs in courtrooms, drawing upon cases from Canada, Britain, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Pakistan. It reviews the Supreme Court of Canada decision R v NS (2012), which denied the request of a sexual assault complainant to wear her niqab during a preliminary inquiry in Toronto. It describes the various Canadian statutes that have used the force of law to prohibit the wearing of the niqab. It offers helpful advice for non-niqab-wearing readers who wish to serve as allies but who are uncertain about what to do to be supportive. Finally, it considers multiple expressions of resistance from niqab-wearing women.

Natasha Bakht examines what our ongoing debates about the niqab have demonstrated about our wider Canadian society. She makes the observation that the plight of niqab-wearing women might help us better understand ourselves. She offers her own views about what the anti-niqab movement reveals about our dominant culture. The weakness of the argument that the niqab must be prohibited in the name of gender equality is one of her most compelling points. We need only juxtapose our own cultural norms of female bodies and their attire to have our anxieties about the niqab thrown into high relief. Why is a society that expresses such concern about women covering their bodies apparently uninterested in the opposite phenomenon? I have sometimes wondered whether we should be asking ourselves more questions about our mainstream culture, with its ubiquitous public imagery of naked sexualized women. I have sometimes wondered why niqab-resisters do not ask themselves why no one has suggested laws to deter cosmetic surgery, artificial breast enhancement, female reproductive organ cosmetic surgery, forms of dress that overexpose female breasts. Does our hyper-sexualized dominant culture acclimatize women into thinking they must unveil themselves in public in order to be acceptable and attractive to the masculine gaze?

This book offers an important contribution to the urgent issues posed by the niqab and anti-Muslim activities in Canada and internationally. It is well-written, carefully organized, coherent, and persuasive. Bakht grasps firm hold of the realities of niqab-wearing women, of the contradictory allegations of the advocates against the niqab, and of the legal dimensions that have exacerbated the debates. Lastly, she offers thoughtful observations about what underlies the objections to the niqab, what such objections reveal about contemporary secular Western culture, and why moving away from prohibitionist thinking would be so beneficial to us all.

In producing this fascinating book, Natasha Bakht has done us a great service. For those who have entrenched themselves on one side or another, and for those who are still pondering, this is a must-read book.

Constance Backhouse, CM, O Ont, FRSC

Professor of Law, University of Ottawa

Ottawa, Canada

Acknowledgements

I AM SO GRATEFUL to the women I interviewed for this project. They were kind, patient, and generous with me and I was inspired by their commitment and courage to living life as they see best despite the many unfortunate obstacles put in their way. My family has been, as always, an immeasurable source of support. They have listened, encouraged, sustained, and distracted (when appropriate). I wish to thank them: Anita Bakht, Baidar Bakht, Heather Brady Bakht, Sacha Bakht, Isaac Sikander Bakht, Isla Veronica Bakht, Carmela Murdocca, Justine Bouquier, Lynda Collins, and Elaan Das Bakht.

Next page