Published in 2018 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2018 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hurt, Avery Elizabeth, author.

Title: Women in politics / Avery Elizabeth Hurt.

Description: New York : Rosen Publishing, [2018] | Series: Women in the world | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016056736 | ISBN 9781508174493 (library bound book)

Subjects: LCSH: WomenPolitical activity.

Classification: LCC HQ1236 .H885 2018 | DDC 324.082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016056736

Manufactured in China

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

THE RADICAL NOTION

CHAPTER 2

WHY NOT RUN

CHAPTER 3

WHEN WOMEN RUN

CHAPTER 4

CRITICAL MASS

CHAPTER 5

WOMEN BELONG IN THE HOUSE... AND IN THE SENATE (BUT HOW DO WE GET THEM THERE?)

GLOSSARY

FOR MORE INFORMATION

FOR FURTHER READING

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

W hen Hillary Clinton conceded her loss to Barack Obama in the 2008 Democratic primary election, she told her supporters, Although we werent able to shatter that highest, hardest glass ceiling this time, thanks to you, its got about 18 million cracks in it. The path will be easier next time. The path wasnt easy; Clinton came heartbreakingly close in 2016 but was not quite able to win her bid for the nations highest office. But by becoming the first woman presidential nominee of a major political party, she did put a lot more cracks in that ceiling.

A glass ceiling is a metaphor typically used to describe that level of achievement in business that women find it difficult, if not impossible, to get beyond. The metaphorical ceiling is glass because it is unacknowledged. People pretend that there is no barrier, that women can go just as high in their chosen professions as men do. But still, all too often, women get to a certain level and can go no farther. Very few women head large corporations. But some do. In business that ceiling has been broken, at least occasionally. In the United States government, however, that ceiling is proving quite stubborn indeed. Almost one hundred years after women got the right to vote, still no woman has been elected president. The situation in the US Congress is not much better21 percent of members of the Senate and 19.4 percent of members of the House of Representatives are female. In Canada (which briefly had a female prime minister in 1993) the percentage of female legislators is slightly higher at 26 percent.

Luisa Dias Diogo became the first female prime minister of Mozambique in 2004. Under her leadership, the nations economy and standard of living improved considerably.

Other countries have done betterbut not that much better. Though women make up slightly more than half of the world population, they struggle to stay at 20 percent of the members of the worlds legislative bodies. Worldwide there are fewer than twenty women heads of state. The reasons for this are not at all clear. Particularly in the West, there is no shortage of women who are more than qualified to run for and to serve in elected office. And when polled, voters say they are willing to elect women. Yet women are not even close to reflecting in government their numbers in the population. That 20 percent ceiling in legislatures is proving to be as stubborn as that highest glass ceiling.

This text will take a look at many of the possible reasons women are less likely than men to run for office and the reasons it is still so difficult to persuade voters to support women when they do run for high office. We will see what happens when women do achieve power, in the United States as well as in other countries, and why electing more women may change the fate of the worldat the very least change the way the world is governed. We will close with a look at what it might take to finally break that highest glass ceiling and to get as many women as men in politics.

CHAPTER 1

THE RADICAL NOTION

Feminism is the radical notion

that women are people.

Marie Shear

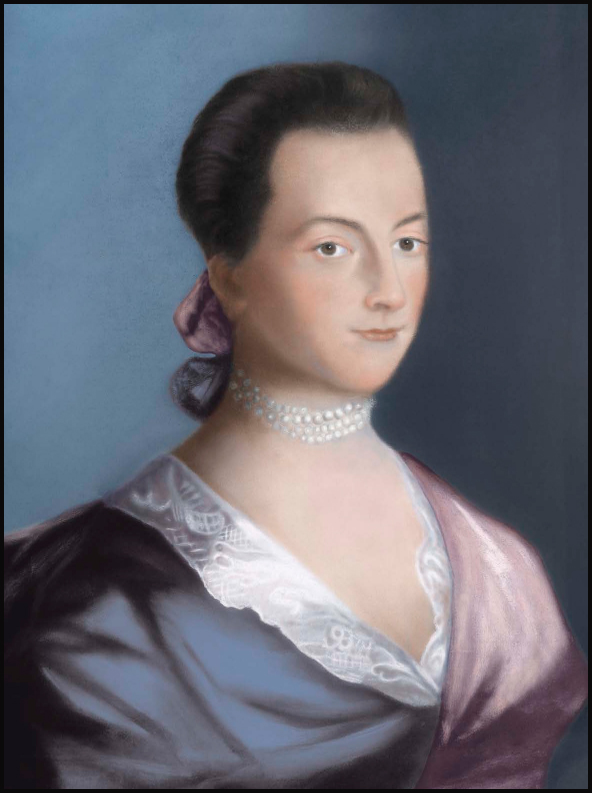

W hen John Adams was in Philadelphia in 1776 making plans for a new nation, he received a letter from his wife, Abigail. She wrote, And by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. She continued to press her case on behalf of the women of the soon-to-be nation: We are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.

Unusual for her time, Abigail Adams believed that women should be educated and should help their husbands make decisions about family matters.

Johns reply to his beloved wife was an affectionate and amused comment about how saucy she was.

We cant be sure today whether Abigail was indeed just being saucy or if she was expressing a nascent feminism, truly calling for some kind of voice for women (if not true equality) to be spelled out in the constitution of the new nation. It is clear from her remarks, however, that she was using the very same argument that the colonists used against King George when they declared no taxation without representation.

In any case, nothing in the constitution of the new country made mention of the rights of women; it did not give women the right to vote or to stand for elected office. That would be a long time coming.

FROM PHILADELPHIA TO SENECA FALLS

The ladies waited seventy-two years to foment their rebellion, but foment it they did. In 1848, abolitionists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott hastily organized the first womens rights convention in American history. The meeting was held in a small church in Seneca Falls, New York, and although only three hundred people attended (forty of them men, including freed slave and newspaper editor Frederick Douglass), the convention marked the beginning of a womens rights movement that is still ongoing today.

One of the founding mothers of the womens rights movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton began her life as an activist working for the abolition of slavery.

The official document stating the position and demands of the convention was called the Declaration of Sentiments. It was based on the US Declaration of Independence and demanded the recognition of women as equal members of society. The opening lines of the Declaration of Sentiments differed from that previous document by only two wordsbut crucial words they were: We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men