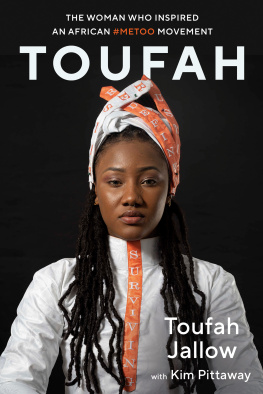

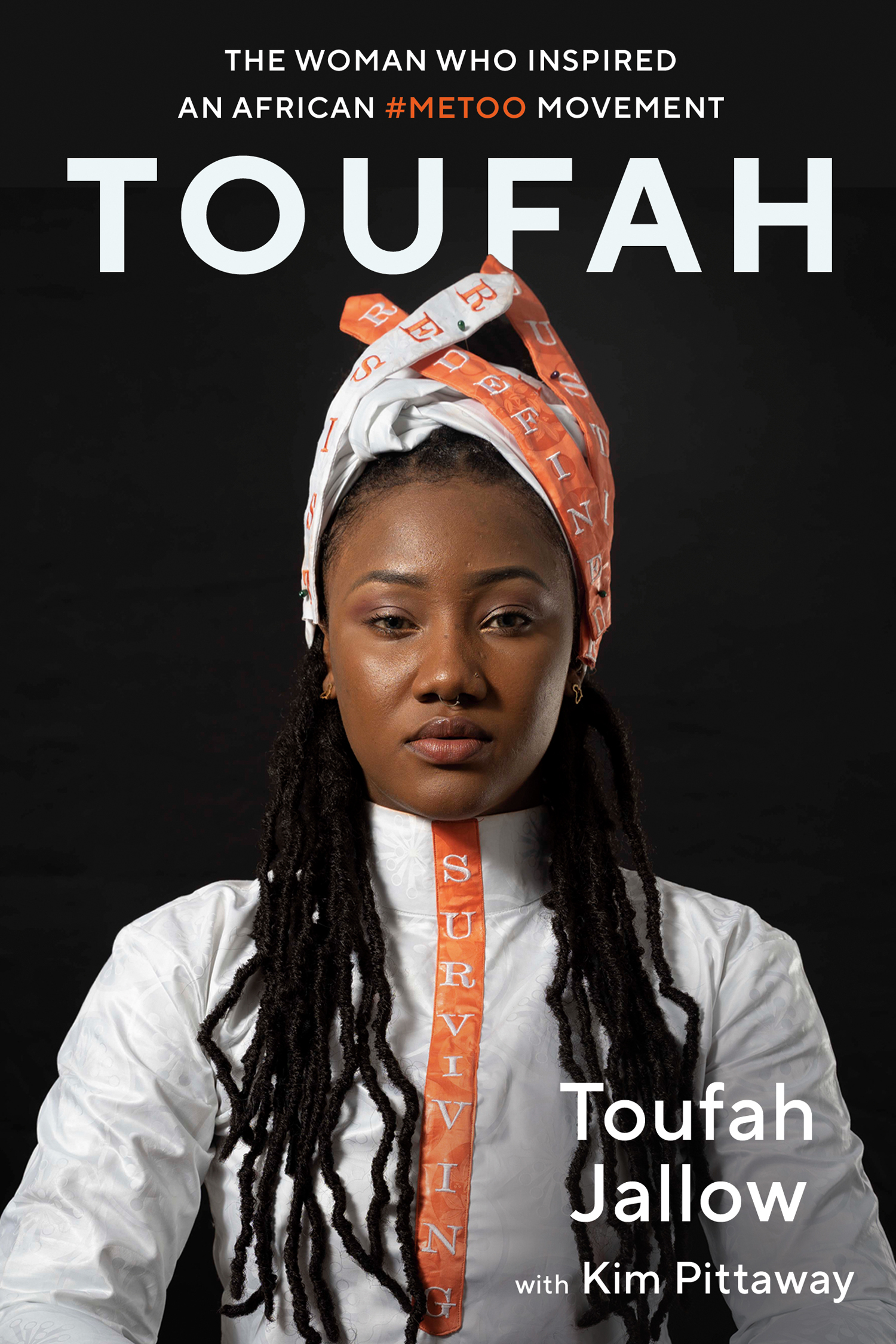

Praise for TOUFAH

My (s)heroes do not wear capes. My (s)heroes call out injustices in the world with enough grace and forgiveness to heal anyone who hears their story. Toufah is that graceful shero the world desperately needs. Toufah is the graceful shero the world is better for.

Celina Caesar-Chavannes, author of Can You Hear Me Now?

This book is not an easy read, but I couldnt put it down. Toufahs story is horrifying and infuriating, but ultimately also hopeful and inspiring because of what she was able to achieve out of such darkness. To anyone who cares about addressing gender-based violence, this is essential reading.

Robyn Doolittle, investigative reporter and author of Had It Coming and Crazy Town

It would be courageous enough for Toufah Jallow to have confronted the man who sexually assaulted her in a society where there is no word for rape. But her decision to expose a man with tremendous powerthe longtime dictator of The Gambia, her home countryis extraordinary. I am in awe of Toufah: to be so young and yet to have such clarity and bravery when confronted with that level of power. She is a rare person, and many will take valuable lessons from her story. This terrific book had me on the edge of my seat, and sends an inspiring message to all women about the power of their voice.

Anna Maria Tremonti, journalist and broadcaster/podcaster

[A] riveting autobiography. The tale of Jallows escape is harrowing and propulsive. While her trauma is extreme, the real story takes place in its aftermath, in the ways it defined the victims life. It takes extraordinary courage and vision to induce social change in a single lifetime, and Jallow has done just that.

The New York Times

Frank and conversational. [Toufah Jallow] peppers her harrowing story with moments of humor and humanity that make the book an inspirational page-turner. Jallows emotional trajectory is particularly compelling. Throughout the book, she vividly describes her fear, strength, and sorrow, always cognizant that her experience, no matter how raw, can be a source of comfort to fellow survivors who are unable to go public. A fiercely readable, potent memoir of a survivor who refuses to be silenced.

Kirkus Reviews (starred)

In this captivating debut, Jallow, a sexual assault victim advocate, shares her harrowing account of survival. This powerful story shouldnt be missed.

Publishers Weekly (starred)

PUBLISHED BY RANDOM HOUSE CANADA

Copyright 2021 Toufah Fatou Jallow

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2022 by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. First published in 2021 in the United States of America by Steerforth Press, New York. Distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Random House Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Toufah : the woman who inspired an African #MeToo movement / Toufah Jallow.

Names: Jallow, Toufah, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210154055 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210154187 | ISBN 9780735282322 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735282339 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Jallow, Toufah. | LCSH: WomenGambiaSocial conditions. | LCSH: MeToo movementGambia. | LCSH: WomenGambiaBiography. | LCSH: Rape victimsGambiaBiography. | LCSH: RefugeesGambiaBiography. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC HQ1817 .J35 2021 | DDC 305.42096651dc23

Text design: Leah Springate

Cover design: Leah Springate

Cover image courtesy of The Toufah Foundation

a_prh_6.0_139089996_c0_r0

To all victims whose rapists are not presidents. To all survivors who have paid for survival with silence. May the whispers of our mothers, their mothers and the mothers before them rise in our throats. I hope we find safety in speaking together.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

ALLEGEDLY

It is December 2020. I sit in front of a computer screen with my friend and colleague Marion Volkmann-Brandau, watching the rough edit of a short documentary we are producing together. Over the course of twenty-five minutes, clips of me competing in a 2014 Gambian scholarship pageant are intercut with images of the man who ruled my country for more than two decades, an all-powerful dictator whose death squad murdered and tortured at his command. Clips of powerful men from other countries appear as well: Harvey Weinstein, who used his position in the film industry to intimidate women into having sex with him. Jeffrey Epstein, who trafficked teenaged girls and young women. Mexican drug lord El Chapo, who declared that young girls were his vitamins because raping them gave him life.

Should I add allegedly?

It has been six years since I was declared the winner of a national pageant sponsored by my countrys president, promised a scholarship to study anywhere in the world as my prize. Instead, President Yahya Jammeh raped me. I became a victim in The Gambia, was a fugitive in Senegal and then a refugee in Canada. At nineteen, I started my life over, a survivor of rape, separated from my family, afraid I would never see them again, worried they would suffer if I told anyone what had happened to me.

Should I add allegedly?

As I rebuilt my life seven thousand kilometres away from the country Id grown up in, I struggled. With depression. With my secret. With loneliness. And then the dictator whose crimes had forced me to flee was deposed and driven out of The Gambia himself. I was able to return, to reunite with my family and, eventually, to tell my story, first to human rights investigators, then to international media like the New York Times, the Guardian, the BBC and CBC, and my countrys Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC).

But people kept telling me I should always say allegedly.

The strange thing is people and institutions arent nearly as adamant that allegedly be attached as a qualifier when they speak of murders ordered by Jammeh, when they talk of torture carried out at his instruction, when they detail financial crimes committed as he drained the countrys coffers. No one attaches allegedly even to his claims of curing cancer with herbal treatments.

This insistence on using allegedly when it comes to rape cant be explained away as simply protecting the rights of those not convicted, because the word isnt just attached to the person named as perpetrator; it is attached to the crime itself. He allegedly raped her morphs into she was allegedly raped. And it isnt something that happens only in The Gambia, only with Jammeh. As I watch the news in my small apartment in Toronto, I notice the same tendency in reports about other crimes in Canada and abroad: when men say they were beaten or assaulted, the word allegedly is rarely inserted. When someone says theyve been robbed, allegedly almost never appears. But when a woman says she was raped, her assertion is often framed as she claimed she was raped or she was allegedly raped. Whether in The Gambia or Canada or the United States or the United Kingdom, when women say they were raped, the men they accuse are given the benefit of the doubt. The women? They are simply doubted.