OCCUPIED WITH NONVIOLENCE

OCCUPIED

WITH

NONVIOLENCE

A PALESTINIAN WOMAN SPEAKS

JEAN ZARU

EDITED BY

DIANA L. ECK AND MARLA SCHRADER

FOREWORD BY

ROSEMARY RADFORD RUETHER

To the loving memory of my mother, Azeezeh Mikhail

CONTENTS

ix

Rosemary Radford Ruether

Xix

Diana L. Eck

xxiii

ILLUSTRATIONS

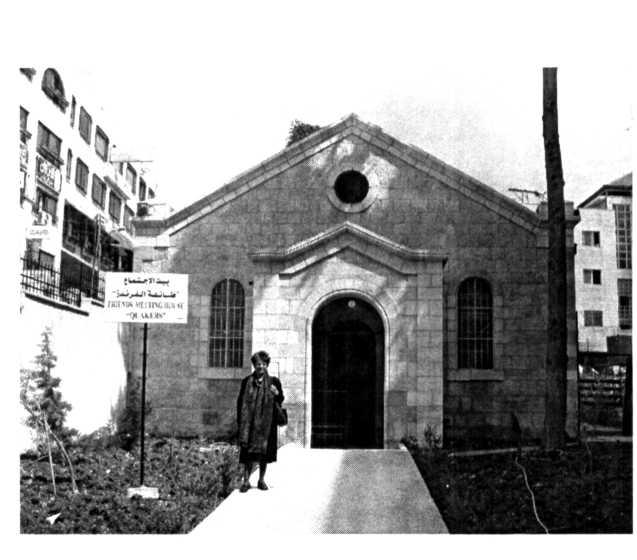

x Jean Zaru, standing in front of the Quaker Meeting House in Ramallah, where she serves as Presiding Clerk. Photo courtesy of Jean Zaru.

20 The "apartheid wall" around Bethlehem, separating the State of Israel from the Palestinians on the West Bank. Photo courtesy of Jean Zaru.

28 Graffiti on the "apartheid wall" around Bethlehem. Photo Julie Rowe. Used by permission.

80 Another view of the "apartheid wall" around Bethlehem. Photo Julie Rowe. Used by permission.

94 The city of Bethlehem hides behind the checkpoint in the separation wall. The "Peace Be With You" mural was added by the Israeli Ministry of Tourism. Photo Julie Rowe. Used by permission.

104 Jean Zaru speaking with Emily Mmreko from South Africa, a member of the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI). EAPPI is a World Council of Churches organization that seeks to support local and international efforts to end the Israeli occupation and bring a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with a just peace, based on international law and relevant UN resolutions. Photo courtesy of Jean Zaru.

140 Jean Zaru, in front of the Quaker Meeting House in Ramallah. Photo courtesy of Jean Zaru.

FOREWORD

Rosemary Radford Ruether

r "HIS BOOK OF ESSAYS introduces to the English-speaking world a very important voice for peace with justice from the heart of the contested world of Palestine. This is Jean Zaru, a Christian Palestinian from Ramallah, a Quaker who for many years has served as clerk of the Friends Meeting in that town. Jean Zaru speaks from the center of her being as a Palestinian Christian woman, committed to transforming the ways in which Israelis and Palestinians, the West and the Middle East, Christians, Jews, and Muslims have been taught to think of each other as implacable enemies.

r "HIS BOOK OF ESSAYS introduces to the English-speaking world a very important voice for peace with justice from the heart of the contested world of Palestine. This is Jean Zaru, a Christian Palestinian from Ramallah, a Quaker who for many years has served as clerk of the Friends Meeting in that town. Jean Zaru speaks from the center of her being as a Palestinian Christian woman, committed to transforming the ways in which Israelis and Palestinians, the West and the Middle East, Christians, Jews, and Muslims have been taught to think of each other as implacable enemies.

Jean Zaru's testimony is twofold. On the one hand, she continually seeks to deconstruct the ways in which the Israeli government and the Western world misrepresent the Palestinian reality, covering up the structures of violence and oppression that are the underlying cause of Palestinian resistance. On the other hand, she constantly holds out another alternative, the way of being good neighbors who recognize the humanity of each side and their necessary interdependence with each other. Jean Zaru recognizes the depths of the challenge that she lives as a daily reality, not to succumb to hatred of the Israeli Jew whose overweening power rains down increasing humiliation and violence upon her people, but to protest this injustice in all its aspects, without losing sight of the human face of the "enemy" as neighbor and potential friend.

These essays represent the many talks that Jean Zaru has given around the world over the last twenty-five years. These talks have been given in many venues in Europe, the United States, and around the world. During this time, Zaru has served as a member of the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches, where she also served as a member of the working group on interfaith dialogue. She has been a council member of the World Conference on Religion and Peace. She has been a visiting scholar at Hartford Seminary in Hartford, Connecticut, a fellow at Selly Oaks College in England, and a participant in the Pluralism Project on Women, Religion, and Social Change at Harvard University. She has also served as a leader in the world, regional, and local YWCA. In addition, she is a founding member and leader in the Sabeel Center on Palestinian Liberation Theology in Jerusalem. Most recently, she spearheaded the project to restore the historic Friends Meeting House in the center of downtown Ramallah and create there the Friends International Center dedicated to building a culture of peace and nonviolence.

Since these talks have been given around the world, often to audiences somewhat ignorant of and conditioned by prejudices about Palestinian history and reality, there is some overlap and repetition between them. Again and again Jean Zaru finds herself in situations where she has to deconstruct these prejudices to try to convey something of what it means to live under Israeli occupation to those who have little experience of these realities. In some Western Christian audiences Zaru encounters built-in resistance to her message. Often these Christians have been conditioned to believe that their primary task is unilateral support for the state of Israel in order to compensate for the Holocaust and Christian anti-semitism. Any critique of Israel's treatment of the Palestinians is considered "anti-semitism."

Such Christians have difficulty rethinking this view and realizing that repentance for anti-semitism does not mean silencing the Palestinian story. Collaborating in Palestinian oppression is not a valid way of paying for their own historic guilt of oppression of Jews! Rather, they need to oppose injustice wherever it is happening, whether it be Christian oppression of Jews in Europe or Israeli oppression of Palestinians today. Our cause must he one cause of justice for all humanity, not just the silent collaboration in one oppression to pay for an earlier oppression, a mentality that simply continues the cycle of violence. This is jean Zaru's message that she struggles to convey, often to fearful and conflicted Western audiences.

Jean Zaru tells the Palestinian story through the lens of her own life and that of her family, her parents and grandparents, siblings, children, and grandchildren. Through the stories of her own concrete experience she tries to convey to Western audiences what it has meant to live in Palestine over the last sixty-five years. She takes them to the experiences of her childhood when Palestinian refugees were expelled from their homes and lands during the 1948 war and her family struggled to shelter many of these homeless people in their own home and gardens. She paints pictures of what it meant to be a teacher at the Friends School in Ramallah over two decades when their students had to live under curfew and interrogation by Israeli military authorities for nonviolent protest against occupation.

Jean Zaru uses her daily life to illustrate what it means to be ghettoized in increasingly shrinking Palestinian enclaves where one can no longer travel to Jerusalem, a mere ten miles to the south, for meetings, shopping, worship, or health care without the greatest difficulty. She shows us what it means for the Palestinian enclaves to be cut off from one another, to be unable to travel to meet with Palestinians in Nablus or Bethlehem, much less to Gaza, where the people have been totally cut off from Israel and the rest of Palestine for many years. Through her eyes we experience what it means to have to travel to Amman, Jordan, for a back operation, what should be a two-hour trip that stretches into two days because of long waits at checkpoints, and having to bump over back roads because Palestinians cannot use the main roads constructed for Israelis only.

r "HIS BOOK OF ESSAYS introduces to the English-speaking world a very important voice for peace with justice from the heart of the contested world of Palestine. This is Jean Zaru, a Christian Palestinian from Ramallah, a Quaker who for many years has served as clerk of the Friends Meeting in that town. Jean Zaru speaks from the center of her being as a Palestinian Christian woman, committed to transforming the ways in which Israelis and Palestinians, the West and the Middle East, Christians, Jews, and Muslims have been taught to think of each other as implacable enemies.

r "HIS BOOK OF ESSAYS introduces to the English-speaking world a very important voice for peace with justice from the heart of the contested world of Palestine. This is Jean Zaru, a Christian Palestinian from Ramallah, a Quaker who for many years has served as clerk of the Friends Meeting in that town. Jean Zaru speaks from the center of her being as a Palestinian Christian woman, committed to transforming the ways in which Israelis and Palestinians, the West and the Middle East, Christians, Jews, and Muslims have been taught to think of each other as implacable enemies.