STRANGERS in the HOUSE

RAJA SHEHADEH is the author of the highly praised memoir Palestinian Walks, which won the Orwell Prize in 2008. He also wrote the enormously acclaimed When the Bulbul Stopped Singing, which was made into a stage play. He is a Palestinian lawyer and writer who lives in Ramallah. He is a founder of the pioneering, non-partisan human rights organisation Al-Haq, an affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists, and the author of several books about international law, human rights and the Middle East.

Also by Raja Shehadeh

When the Bulbul Stopped Singing

Palestinian Walks

STRANGERS in the HOUSE

RAJA SHEHADEH

This edition published in 2009

First published in Great Britain in 2002 by

Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London ECIR OJH

www.profilebooks.com

First printed in America in 2002 by

Steerforth Press

Copyright Raja Shehadeh, 2002, 2009

Foreword copyright Anthony Lewis, 2002

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 250 6

FOREWORD

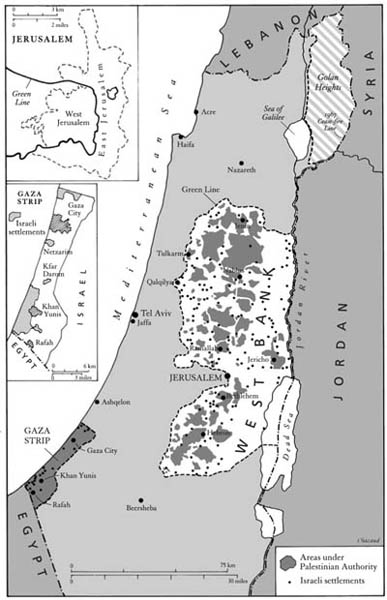

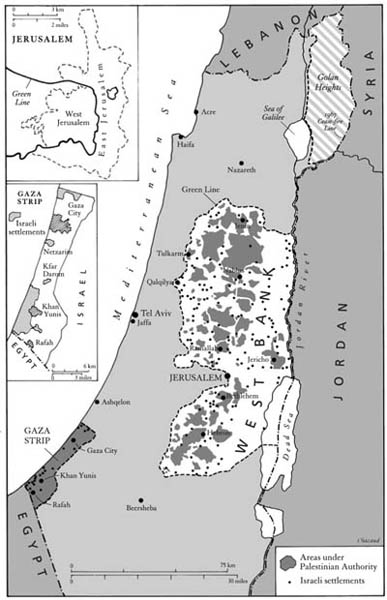

IN 1978 I met a Palestinian lawyer, Aziz Shehadeh, who was a fellow at Harvard Universitys Center for International Affairs that year. It was a time when Palestinian and other Arab leaders refused to accept the existence of Israel. Shehadeh had a different view. He believed that the West Bank and Gaza, then under Israeli military rule, should become a Palestinian state and live in peace alongside Israel. Aziz was a brave man: braver than I understood at the time. Back home in Ramallah, in the West Bank, Palestinian radio broadcasting from Damascus called him a traitor who wanted to surrender and sell our birthright. He was threatened with death. Aziz told his son Raja that he understood why he was being attacked: He was challenging the accepted wisdom of Arab leaders, which was that there could be no compromise with Israel. Under that empty policy, Palestinians had lost much in 1948 and more in 1967, and they would continue losing if their leaders stuck to the fantasy of making Israel disappear.

Raja Shehadah is his fathers son in the realism and humanity of his view on the conflict with Israel. But he is a very different person: more worldly, more Western, less gripped by the traditions of Arab culture and family life. The differences led to tension with his father. This book is the story of the relationship between son and father, a difficult, often painful relationship, with understanding cut short by the fathers brutal and still unsolved murder.

It is not a political book. As Raja explained, I wanted to tell a personal story, to celebrate life rather than settle scores or vent anger. Yet in a hundred different ways it is political. Even in exploring the heartache he experienced in yearning for a father who would pay more attention to my needs as a young man growing up under difficult circumstances, he shatters the stereotype many Americans have of Palestinians. Hath not a Palestinian senses, affections, passions?

The Israeli occupation of his homeland is only the backdrop for the events Raja Shehadeh describes not, say, the subject of a critical broadside. But no one can read his book without coming to understand the lawlessness, the vindictiveness that were practiced in the name of military necessity. They were simply a part of lifes daily humiliations.

Raja Shehadeh founded a human rights group, Al Haq, that monitored legal conditions under the occupation. It was careful in its research and respected for its fealty to law; it was affiliated with the International Commission of Jurists. But Israeli military officers treated it with suspicion and contempt, taking its field workers into detention, harassing Shehadeh and even invading his fathers law office and ransacking it. Then they imposed a huge fine on the Shehadeh firm for not paying a value added tax that Israel had just imposed on the occupied territories. Al Haq took the view that it was illegal for the occupiers to introduce a new tax, and no one was paying it. The Israeli authorities selected the Shehadeh law firm for exemplary punishment, no doubt, because of Rajas role in Al Haq.

All this comes into Rajas story only as a point of conflict with his father. Aziz was afraid that Rajas work with Al Haq made him vulnerable to violent attack. He wanted Raja to practice law in the old way, without challenging the occupation authorities. Not that Aziz lacked the courage to stand by principle. He not only took real risks by calling for compromise with Israel. Years before, he had agreed to be the defense lawyer for the men charged with the assassination of King Abdullah of Jordan; that made him suspect with the royal family that ruled the West Bank as well as Jordan until 1967.

The book gives us an insight into a characteristic that most Palestinians share: the sense of loss. The Shehadeh family had lived in Jaffa, the old Arab city adjoining Tel Aviv. From his earliest childhood Raja heard about the wonders of that former life: the strolls on the beach, the nightlife. There were daily reminders of that cataclysmic fall from grace. That was in 1948, when the family fled to what had been its summer house in Ramallah.

But Aziz Shehadeh did not spend his life looking longingly at the past, and neither has his son. Too many Palestinians did, at least until at Oslo in 1993 the PLO agreed to mutual recognition with Israel. We spent those years, Shehadeh writes of his people, lamenting, whining, complaining, bemoaning the lost country. And meanwhile losing more, bit by bit.

It is the continuing loss of the Palestinian homeland that makes the most painful reading in this book. Years ago I took a long, arduous walk with Raja through a beautiful wadi, a valley untouched by development. Now it has been destroyed by Jewish settlements and the bypass roads that connect them to Israel. The story is the same in much of the West Bank. The occupiers bulldozers have carved up the hills that gave the West Bank what visitors thought of as its biblical appearance.

When I have visited the West Bank over the years, it was the physical impact of the occupation that struck me the hardest the rows of identical houses in the settlements, the bulldozing of olive groves. Shehadeh captures that as well as anyone I have read. Most of these hills had never been smitten by the curse of machines. They had remained more or less unchanged since the time of the Prophets. But now it has changed. The earth was turned over, sliced and cut and reconstructed. The terracing disappeared, and in its place wide expanses of flat land were created on which ready-made houses would be perched....

For a time Raja Shehadeh played a part in the efforts to reach agreement with Israel. At one stage of the endless negotiations he was legal advisor to the Palestinian delegation. But over the years, seeing his land smitten and finding no redeeming vision among political leaders, he has given up all participation in political life and even in human rights work. He practices law and cultivates his garden: his metaphoric garden. Which is to say that he writes.

Next page