SEEKING PALESTINE

New Palestinian Writing

on Exile and Home

First American edition published in 2013 by

OLIVE BRANCH PRESS

An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc.

46 Crosby Street

Northampton, Massachusetts 01060

www.interlinkbooks.com

Copyright Women Unlimited 2013

Copyright for individual essays is retained by the authors, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without

the prior permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-56656-906-4

Images on pages 2-3, 72-73, 150-51: Emily Jacir

Where We Come From 2001-2003 (three details)

American passport, 30 texts, 32 c-prints and 1 video

Copyright: Emily Jacir

Courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York

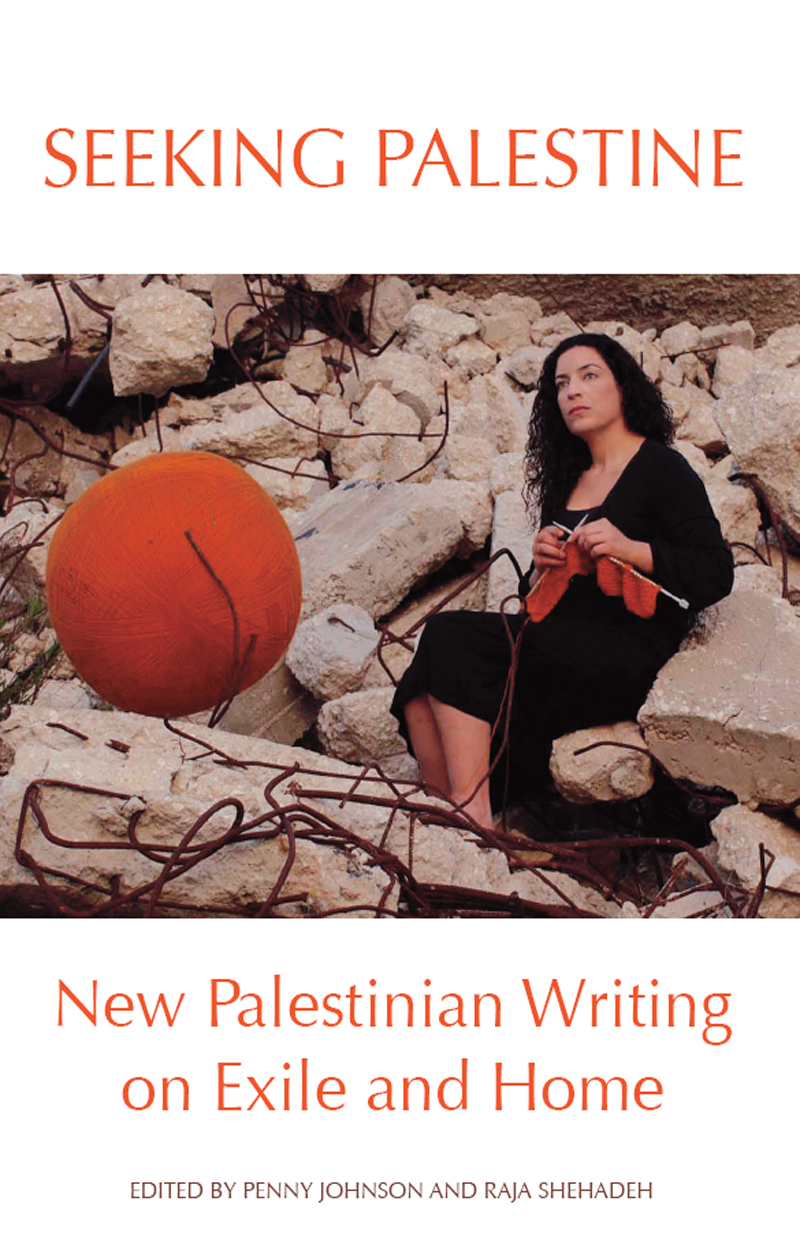

Cover photograph: Raeda Saadeh

Printed and bound in the United States of America

To order our free 52-page, full-color catalog, call us at

1-800-238-LINK or visit www.interlinkbooks.com

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to the Palestine Festival of Literature (Palfest) where the idea of this book was born, in one of the many wonderful encounters Palfest fosters between international writers, editors and publishers, and their Palestinian counterparts. The editors of Seeking Palestine are pleased to dedicate their royalties to Palfest, as a small contribution to continuing the conversation and breaking the barriers.

Contents

PENNY JOHNSON

Introduction: Neither Homeland nor Exile are Words

EXILE/HOME

My Country: Distant as My Heart from Me

HOME/EXILE

My Country: Close to Me as My Prison

AT HOME IN WHAT WORLD?

A Place to Live and Curse in

PENNY JOHNSON

Introduction:

Neither Homeland nor Exile

are Words

In this volume, historian Beshara Doumani recalls a song from World War II Haifaa song that Doumani cannot place in any archive, even though he possesses two almost translucent pieces of paper with the ditty scrawled in his own childish handwriting. Indeed, he can sing this sailors songand it onlyin an accent from a vanished Haifa neighborhood. It is not nostalgia, but wonder and questioning that inform his reflections. In an encounter between memory and imagination, a rootless memory becomes a miracle of immaculate birth.

Writing outside the archives, new Palestinian writing on exile and home asks questions laced with wonder. How do Palestinians live, imagine and think about home and exile six decades after the dismemberment of historic Palestine and in the complicated present tense of a truncated and transitory Palestine? What happens when the idea of Palestine that animated so many around the globe becomes an Authority and Palestine a patchwork of divided territory? When we, my co-editor Raja Shehadeh and I, asked Palestinian essayists, novelists, poets and critics to respond, we found ourselves on new groundfascinating, intimate and provocative. And it seemed very much like our writers were conversing with each otherand with Palestinian writers before themexchanging memories, reflections, an occasional joke or a poignant moment of sorrow, like friends on a summer night in the cool hills of Palestine or at the corner caf in New York or on the terrace over the sea in Beirut. Wherever they were, the tone was convivial, the talk exhilarating, and the memories unconventional, both personal and worldly. Seeking Palestine , then, is not a representative anthology this was neither the editors intention nor their aptitude; for an excellent anthology of Palestinian writing until the early 1990s, the reader should turn to Salma Khadra Jayyusis magisterial Anthology of Modern Palestinian Writing . Our book is in an intimate key and its claim is to imagine, rather than represent.

Indeed, our writers sidestep representation and imaginatively affirm new ways of being Palestinian, giving their own resonating and contemplative answers to the worlds stock questions. By now, the treacherous politics of representation are perhaps all too familiar. But the terrain of imagination and memory, which this anthologys writers navigate with elegance and sensitivity, is also potent, though perilous. Even as they recognize memorys function as a means of resistance and of belonging, our writers avoid the obvious trap of nostalgic memory and are aware that memory-as-reclamation is a vexed project: as the novelist Mischa Hiller points out, when the exiled and dispossessed remember Palestine, whether experienced or imagined, their memories might seem quite alien (and alienating) to the Palestinians who live there now.

While Doumani seeks to transform his miracle memory into a mortal oneone that can be forgotten, with all the privileges of security that such forgetting impliesSuad Amiry fights against memories, those iconic images that have haunted Palestinians for over sixty years since the 1948 Nakba when Palestine was dismembered. Her words are a drumbeat of Noes addressed to her obsession, Palestine. She writes:

And it would not be about the blooming almond trees and the red flowering pomegranates that were not tenderly picked in the spring of 1948 nor in the summer after.

But Amirys roll-call of insistent noes, like a photo negative, both reverses and preserves these inescapable images. And, in fact, her prose-poem is inspired by a telling phrase of Mahmoud Darwishs that heads one of this volumes sections: my country: close to me as my prison. And her denial of the memory of almond trees perhaps brings their blooming even more persistently into the imagination. Darwishs evocation of blossoming almonds in a late poem written from his exile in Ramallah comes to mind:

Neither homeland nor exile are words,

But passions of whiteness in a

Description of the almond blossom

If a writer were to compose a successful piece

Describing an almond blossom, the fog would rise

From the hills, and people, all the people, would say:

This is it.

These are the words of our national anthem.

The writers here also refuse homeland and exile as mere words, and search for waysimages, fragments, memoriesto lift the fog from the hills. Raja Shehadeh peers through a gossamer veil of white fog on a 2003 visit to the Israeli-bombed ruins of the Muqataa, at once the current seat of the Palestinian Authority, the past Israeli military headquarters in Ramallah, and a former British Mandate police fortress. In three diary entries of an internal exile, he ponders the layers of meaning of this site and wonders when Palestine/Israel [will] come to mean nothing more to their people than home.

Politically besieged as it is, Palestine evokes a particular obligation of belonging in its far-flung inhabitants for whom insistent memory becomes a mode of habitation. Like Shehadeh, several writers speak of a desire to move beyond this particular kind of identification, to where a robust Palestine can be nothing more than home. Reflecting on the ties that bind him to a country he has never seen, Hiller searches for something bigger-hearted and more inclusive than just a statethe golden thread that not just ties us back to Palestine but pulls us forward to a new one. Hiller thus seeks Palestine not simply in a political entity but in an inclusive vision of Palestine and Palestinian identity; he also shares with Raja Shehadeh a wish for Palestine to be a place that can be home or not, a Palestine that is a choice :