This English translation was made possible by a donation in the memory of Mey and Omar Akashah, may their dream of a free, democratic, secular, and open Palestine become a reality.

The team would like to give special thanks to:

Majdoline Al Ghazawi, godmother of this project.

Helen, Randa, Roula and Sally for their total involvement.

Mona, Hala and Tarek, who supported the printing of the French and English editions.

Abu Samy and Samir A. for their backing.

Father Jean-Michel de Tarragon, assisted by Mr Serge Ngre, who kindly gave digitized images from the archive of old glass-plate negatives of the Dominican Fathers of the cole biblique et archologique franaise of Jerusalem.

The families of the people interviewed, for their trust and warm welcome, as well as: Muhammad Abdulhadi, Hussam Abed, Nazih Abu Nidal, Mohammed Abu Saleh, Dalia Abu Sharar, Salam Abu Sharar, Samaa Abu Sharar, Joumana Al Jabri, Abdel Aziz Al Sayed, Firas Banna, Francisco Javier Bernales, Ghada Bisharat, Nawar Bulbul, Mara Paz and Carlos Chawan, Paula Costabal, Sara Dajani, Reka Deak, Abd Al Fatah Al Kalkili, Akram Al Sharif, Suha Eid, Samah Eriqat, Eduardo Escobar, Vanessa Guno, Rabbieh Hamzah, Wael Hamzah, Haifa Irshaid, Imad Jada, Nina Jada, Fadi Kattan, Ghada Khoury, Johnny Mansour, Samih Masoud, Macarena Meruane, Ayed Nabah, Elena and Ali Qleibo, Rana Safadi, Housep Seferian, Jeanine, Jean-Yves, Rachel, Kamal, Zahira and her family for having pointed us in the right direction.

Contents

Salim Tamari

Professor of Sociology, Birzeit University; Research Associate, Institute for Palestine Studies; Editor, The Jerusalem Quarterly

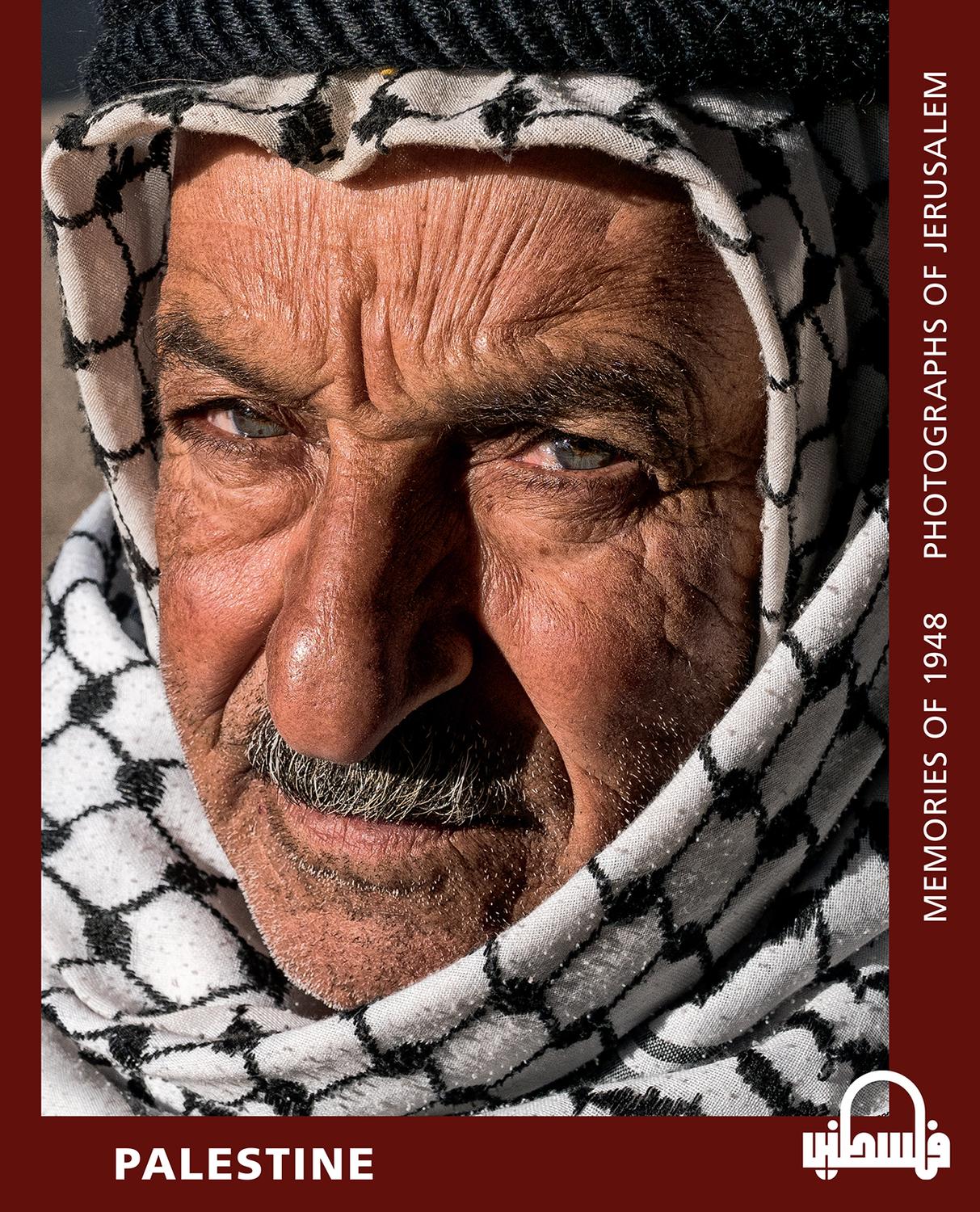

Chris Conti has managed to skilfully bring together some riveting narratives of exile and survival from the war of 1948. A few relate to prominent figures like Latin Patriarch Michel Sabbah, writer Feissal Darraj, and advocate Fuad Shehadeh but the majority are ordinary Palestinians who originally came from Jerusalem or made the city the centre of their lives. Those survival stories are not narratives of heroic resistance, common to the hagiographic literature, but they present us with the subjects defiance and steadfastness against all odds. The stories include satirical, mundane, and tenacious reactions to oppression and exile with the city of Jerusalem as the backdrop to their predicament. The intimate and austere photography of Altair Alcntara provides a poignant reminder that the consequences of 1948 are still with us today.

By Falestin Naili

Historian, Researcher at the French Institute for the Near East (Ifpo)

There are dead who sleep in rooms you will build there are dead who visit their past in places you demolish there are dead who pass over bridges you will construct there are dead who illuminate the night of butterflies, dead who come by dawn to drink their tea with you, as peaceful as your rises left them, so leave, you guests of the place, some vacant seats for your hosts they will read you the terms of peace with the dead!

From The Red Indians Penultimate Speech to the White Man, by Mahmoud D arwish , translation by Fady Joudah

Living Memories

On May 15, 2018, thousands of Palestinian demonstrators gathered on the border between the Gaza Strip and Israel to demand their right to return and to oppose the relocation of the United States Embassy to Jerusalem. Seventy-one years after Al Nakba (1948), these demonstrators, most of whom were under 30 years old, surprised the world by the longevity of their memory. They shouted loudly and strongly about their right to return to nearby villages and neighbouring towns in Gaza, like Ramle, Lydda, Majdal and Jaffa. These young people, who have known no reality other than military occupation, wars and blockades, form part of a collective destiny with 1948 as its tragic point of departure. For them, the border constitutes the line drawn between their lives in the refugee camps of Gaza and the bygone days in the villages and towns of their forefathers, some of which are visible from the border. It is the demarcation between their present reality and a past from which they were forcibly cut off and on which they cannot turn their backs.

In May 2000, similar scenes played out following the retreat of the Israeli army from southern Lebanon. The border, once again accessible after 28 years of military occupation, was the backdrop for visits and family reunions for Palestinian refugees who had settled in Lebanon and their relatives living in the north of Israel. Many Palestinian refugees today live very close to the places they came from but to which they cannot return, even for a visit. Sohaila Shishtawi testifies to this; living in Amman, she is only 80 kilometres away from her native Jerusalem: I recently applied for a visa at the Israeli embassy in Jordan to go and visit my nephew in Jerusalem, but it was turned down. I do not understand; how could an 89-year-old Palestinian woman, 1.4 metres tall and weighing 38 kilos, possibly pose a threat to Israel?

Nevertheless, since 1948, the absentees have been making their presence felt, even if it is physically impossible. The 19 stories offered here illustrate different ways of being present, of counting, of making oneself heard and of having some weight. In the face of erasure imposed through terror, through the destruction of their villages, by being uncounted during population censuses, by being deprived of their right of residence in the face of the confiscation of their property and their marginalization in the dominant historiography on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, 11 men and eight women tell their stories of 1948. They retrace the effects of this historic cataclysm and the different strategies for survival, perseverance, creativity and resistance that they deployed.

These 19 stories obviously cannot cover all of the experiences Palestinians lived through in 1948, but they give a fairly representative idea. From Gaza to Nazareth, the narrators come from towns and villages in different parts of historical Palestine. Today, some live in refugee camps, others in towns and cities in the region or much further afield. They come from different social classes, different professions and represent various degrees of social and political engagement. Some of the stories emanate from public figures such as the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Michel Sabbah and the intellectuals Ilham Abughazaleh and Feissal Darraj, but the majority of the testimonies are those of people who have left no written traces of their experiences. It is thanks to the passionate work of the team of editors that their voices can be heard. This book can thus be seen as a response to the call made some ten years ago by Ahmad Said and Lila Abu Lughod to make it possible for Palestinian stories to slip through the wall of the dominating history of 1948 and open it up to factual and moral questioning.

These very personal stories deal with themes that are often combined: the land and rootedness, creativity and resistance, and finally, the space of the possible.

The collapse of a world

Over and above these themes, these texts evoke the terror, the wrenching and the intense sense of loss experienced by these men and women, the majority of whom were still children during the war of 1948. Depicted by Israel as the war of independence; it has been the subject of many books and special editions of journals; yet until recently, the Palestinian perspective remained marginal. It is in the details of the tragedy afflicting the Palestinians that we find the reasons for its name: