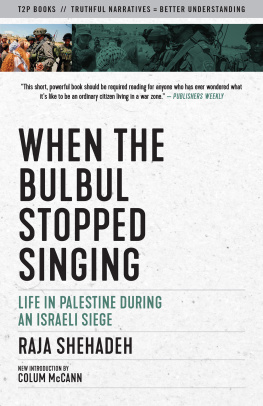

ALSO BY RAJA SHEHADEH

Strangers in the House:

Coming of Age in Occupied Palestine

When the Bulbul Stopped Singing:

A Diary of Ramallah Under Siege

Palestinian Walks:

Notes on a Vanishing Landscape

A Rift in Time:

Travels with my Ottoman Uncle

2012 Raja Shehadeh

Published by OR Books, New York and London

OR Books is a new type of publishing company that embraces progressive change in politics, culture and the business of publishing. We sell our books worldwide, direct to readers. To avoid the waste of unsold copies, we produce our books only when they are wanted, either through print-on-demand or as platform-agnostic e-books. Our approach jettisons the inefficiencies of conventional publishing to better serve readers, writers and the environment. If you would like to find out more about OR Books please visit our website at www.orbooks.com .

First printing 2012

First published in the United Kingdom in 2012 by Profile Books Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-935928-97-3 paperback

ISBN 978-1-935928-98-0 e-book

Printed by BookMobile in the United States. The printed edition of this book comes on Forest Stewardship Council-certified, 30% recycled paper. The printer is 100% wind-powered.

To Leonard Woolf, who answered Virginia upon

being called to listen to Hitler on the radio:

I shant come. Im planting iris, which will be

flowering long after Hitler is gone.

13 DECEMBER 2009

Im just back from a lovely day spent in Wadi Qelt, the ravine on the way between Jerusalem and Jericho. This is one of the few places in the West Bank where you can be sure of finding water even after the drought of the past eight months.

I was with a mixed group of Palestinians and foreigners, photographers and teachers, all of us living and working in the West Bank. Turned out we were not the only ones who had had the idea of an outing there. Just after we put down our rucksacks and stretched out on the rock in the sun a Palestinian family of nine arrived. They were disappointed to find us there but settled for the second-best slab of rock on the opposite side of the pool. Their smaller group comprised two bearded men, two young women with the hijab (headscarf) and another of indeterminate age with the niqab ( face-cover ), and four children. All the women wore long black skirts. As soon as I saw them I wondered how they had managed the rocky path without falling in the water. The women in our group invariably wore jeans and colourful shirts.

I had been thinking as we passed the Israeli checkpoint of how clothes distinguish the various groups in our tiny land. The female Israeli soldiers wore tight khaki trousers, the low waist emphasizing the contours of their hips, and were bedecked with mobile phones. They looked at us through their dark sunglasses, giving orders with their hands while exchanging flirty looks and sexual innuendoes with the male soldiers, with whom they conversed in loud Hebrew. To them we were mere specks on the terrain that belonged exclusively to them and they could move us around with a flick of their little finger like pieces on a chequerboard. They lived in their own world, operating the highly technical security apparatus that they seemed to believe entitled them to an exclusive place in the advanced w estern world.

From the way we appeared and dressed, the sombre-looking family must have suspected that we were Israelis. But there was only a short distance between us. The ravine we were in was deep, with high rock walls bordering it and a pool of water between the slabs on which we spread out that was fed by cascading water from the Fawwar spring, so called because of its sporadic flow. Our fellow picnickers were within earshot and could easily hear us speaking Arabic, so they must soon have realized the nationality of most members of our group. Unfortunately, we did not do what would have been normal a few years ago, perhaps because we drew an imaginary line between us, with them, the suspected Islamists, on one side and us seculars on the other, with the water in between. No one from our side either greeted them or went over to their side to invite them to join us on our rock, which was large enough to accommodate them as well. So a distance was established between us from the beginning, much wider than the natural divide, the small pool of water that separated us.

We spread a red and white checked cloth over the rock and placed on it the different salads and vegetable dishes we had brought with us. We ended with a colourful display, all entirely vegetarian. There was beetroot salad, baba ganoush [an aubergine dip], goats cheese, a bowl of carrots, tomatoes and broccoli, different kinds of patties and fruits. As we settled down to eat, the men from the group opposite left the women and children to search for dry wood for their barbecue of kufta and lamb chops.

I looked at the women who were left behind and couldnt help wondering whether they were feeling uncomfortable being in the open dressed as they were. Wouldnt it be normal to resent the lightly clad women on our side? Of course it would be, no question about it. And yet perhaps they feel they are pious, and will be rewarded in the afterlife, as our group would not. Was it so?

As I was having these thoughts, I saw one of the young women go over and stand facing the rock wall behind the slab on which they sat. She then proceeded to write on it with a piece of charcoal left by a previous picnicker, God leads astray whomsoever H e will, and H e guides whomsoever He will.

As soon as Saba, our husky historian, saw what the young woman was doing he stopped eating, stood up and, turning to her, cried out across the water, What do you think youre doing? Youre defacing the rock. This rock doesnt belong to you. Stop what youre doing immediately.

She stopped at once and returned to her group. The older woman said something to her that we could not hear and she sat down again.

As I waited to see what was going to happen when the men returned I thought of a conversation I had recently had with a young man at Silwadis, the juice shop in the centre of Ramallah.

I had noticed that he offered dates along with the citrus and other fruits he was juicing. I asked him how he used the dates. With milk, he answered. Its a good mixture. After all, dates were the preferred food of the Prophet, peace be upon him.

I then spoke to his assistant, the intense, silent one with a neat beard and large, drooping eyes that were downcast yet watchful and alert. I had often wondered about him.

He had once asked for my help in obtaining a permit for his sister-in-law, who was not being allowed to visit her husband in an Israeli jail. He thought I could help through the human rights organisation Al Haq, with which Im associated. I didnt think Al Haq could help with this, but I did refer him to other organisations that I thought could. Today I asked him about the outcome. He told me that his sister-in-law now has a permit to visit but only once every six months. When she visits they stamp the permit and allow no other visit for another six months. He said they didnt want to stir the pot until after she visits.

Next page