A RIFT IN TIME

RAJA SHEHADEH is the author of the highly praised memoir Strangers in the House, and the enormously acclaimed When the Bulbul Stopped Singing, which was made into a stage play. He is a Palestinian lawyer and writer who lives in Ramallah. He is the founder of the pioneering, non-partisan human rights organisation Al-Haq, an affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists, and the author of several books about international law, human rights and the Middle East. His most recent book, Palestinian Walks won the Orwell Prize in 2008.

ALSO BY RAJA SHEHADEH

When the Bulbul Stopped Singing

Strangers in the House

Palestinian Walks

2011 Raja Shehadeh

Published by OR Books, New York.

(First Published by Profile Books, London, 2010).

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2011.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrival system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data:

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-1-935928-28-7

Ebook ISBN 978-1-935928-29-4

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Widad, my mother, a story teller, who fell silent before she could find out the end of the story

Human beings are capable of the unique trick, creating realities by first imagining them, by experiencing them in their minds. The active imagining somehow makes it real. And what is possible in the art becomes thinkable in life.

Brian Eno

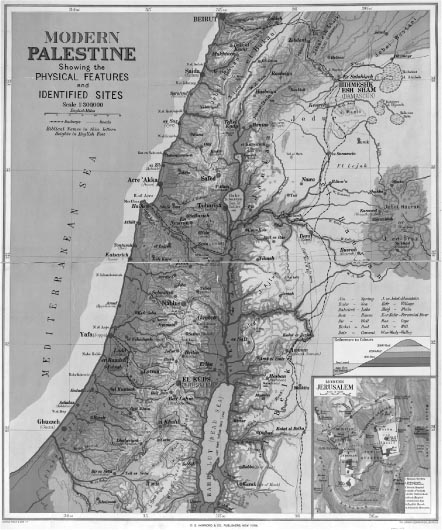

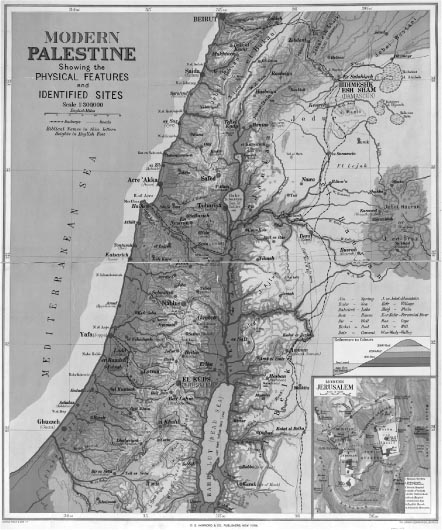

An undated, pre-1916 physical map of northern Palestine and neighbouring regions showing some of the towns, villages and areas mentioned in the text. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

Frontispiece: A Bedouin man and his horse at the Makhada in the Jordan River where Najib forded the river in the course of his great escape.

1

Escaping Arrest

Theyre coming to arrest you, Hanan, my sister-in-law, called to warn me in her strong, matter-of-fact voice. Samer is on his way.

My mother had just called Hanan in a panic to dispatch my brother to my aid, convinced that the Palestinian security police would be at my door any minute. She was frantic. An anonymous official from the office of the Attorney General had rung her to ask about me because they did not have my phone number. Prudently, she refused to reveal it. Dont worry. Well find him, he had menacingly said before hanging up.

I wasted no time. I quickly put on thick underwear, tucked my toothbrush in a pocket and pulled on an extra sweater, prison survival tips learned from experienced security detainees I had represented in the past in Israeli military courts. Jericho, the site of the new Palestinian security prison and the old Israeli military government headquarters, can get very cold at night. On that evening of 18 September 1996 I sat huddled in the courtyard of our new house and waited for the knock on the door, trying to pretend I was neither worried nor angry.

Those first years of the transitional rule of the Palestinian Authority were strange times. It was the rude awakening at the end of a fascinating and hopeful period for me, during which I had devoted all my energies to bringing about change and a conclusion to the Israeli occupation. I had spent years challenging illegal Israeli land acquisitions in the occupied West Bank. Ironically, the unfounded claim that was now being made against my client was that he was selling land to the enemy by going into partnership with an Israeli corporation for the establishment of a gambling casino in Jericho, and I was accused of helping him with this venture. It was a false claim fabricated by some powerful members of the governing Authority who were hoping to intimidate my client into withdrawing from the project so that they could replace him in this lucrative enterprise.

Prompted perhaps by disappointment over the false peace heralded by the signing of the Oslo Accords, and despite all the fanfare on the White House lawn, my thoughts had been turning to the past, to the time when it all began. I had been reading about my great-great-uncle Najib Nassar, who like me was a writer, and like me a man whose hopes had been crushed when the Ottoman authority of his day sent troops to arrest him. But unlike me he did not wait for the knock on the door.

It was from my maternal grandmother, Julia, that I first heard of Najib. But he was always spoken of with ambivalence. He was the odd man out in the Nassar family, the one who was preoccupied with resistance politics during the British Mandate period while his brothers were making a good living, one as a hotelier, another as a medical doctor, a third as a pharmacist, all well-to-do, established members of the professional middle class, while he mingled with the fellaheen, the peasants, and lived for a while among them. Even worse, he associated with the Bedouins, spoke and dressed like them and generally adopted their ways. My grandmother told me about a visit he once made to the family home in the Mediterranean city of Haifa.

We did not recognise him. We almost threw him out. Then he said, Im Najib. We could hardly believe it. He looked emaciated, all skin and bones. His beard was long and straggly, he wore a keffiyeh on his head and he smelt terribly, as he had been living out in the open. I will never forget that sight.

Hearing this, I was intrigued. No one had mentioned the order for his arrest by the Ottoman government. I was left to wonder why he went to live out in the wild. What was he running away from? And why was he so poor? How did he lose his money? Did he gamble it away?

To locate the places where Najib found refuge during his long escape from the Ottoman police, I first used a map made by the Israeli Survey Department. But I soon discovered that, in the course of creating a new country over the ruins of the old, Israel had renamed almost every hill, spring and wadi in Palestine, striking from the map names and often habitations that had been there for centuries. It was the most frustrating endeavour. If only I could visit this area with someone able to read the landscape and point out where the old towns and villages had stood. I knew just the person, but the Palestinian geographer Kamal Abdulfattah was not allowed to cross into Israel from the West Bank. How Israel manages to complicate and frustrate every project!

After the failed attempt at mapping out Najibs escape route using a modern Israeli map, I managed to retrieve a 1933 map from the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh. What a relief it was to look at this and envision the country Najib would have recognised, with the villages, hills and wadis in which he had taken refuge reassuringly marked and bearing the names that he had used.

In planning the route of his escape, Najib had not been hampered by the political borders that many Palestinians are not allowed to cross today. Under the Ottomans on the eve of the First World War there was no administrative unit called Palestine. Haifa, Acre, Safad and Tiberias were part of the Beirut