Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

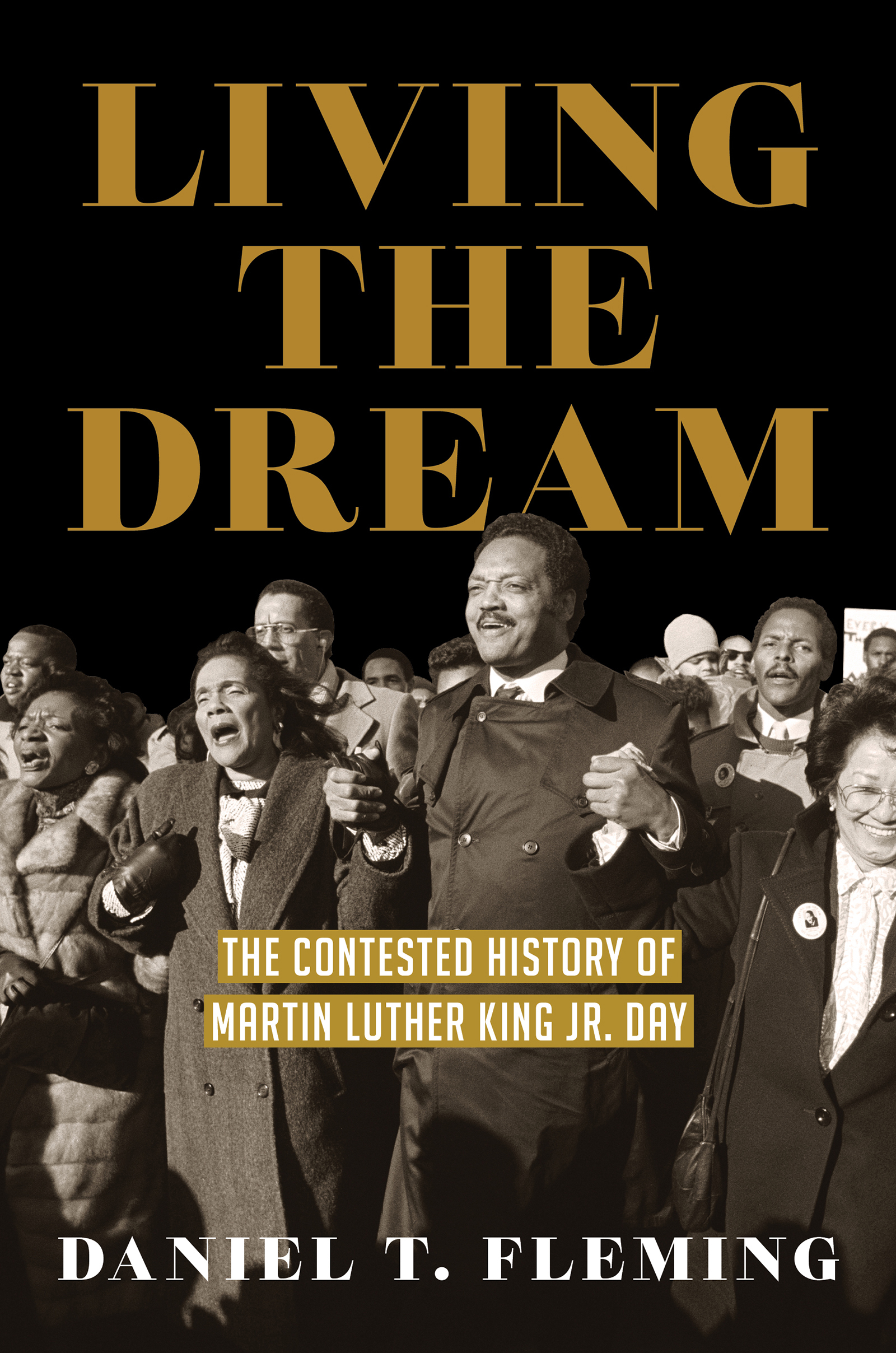

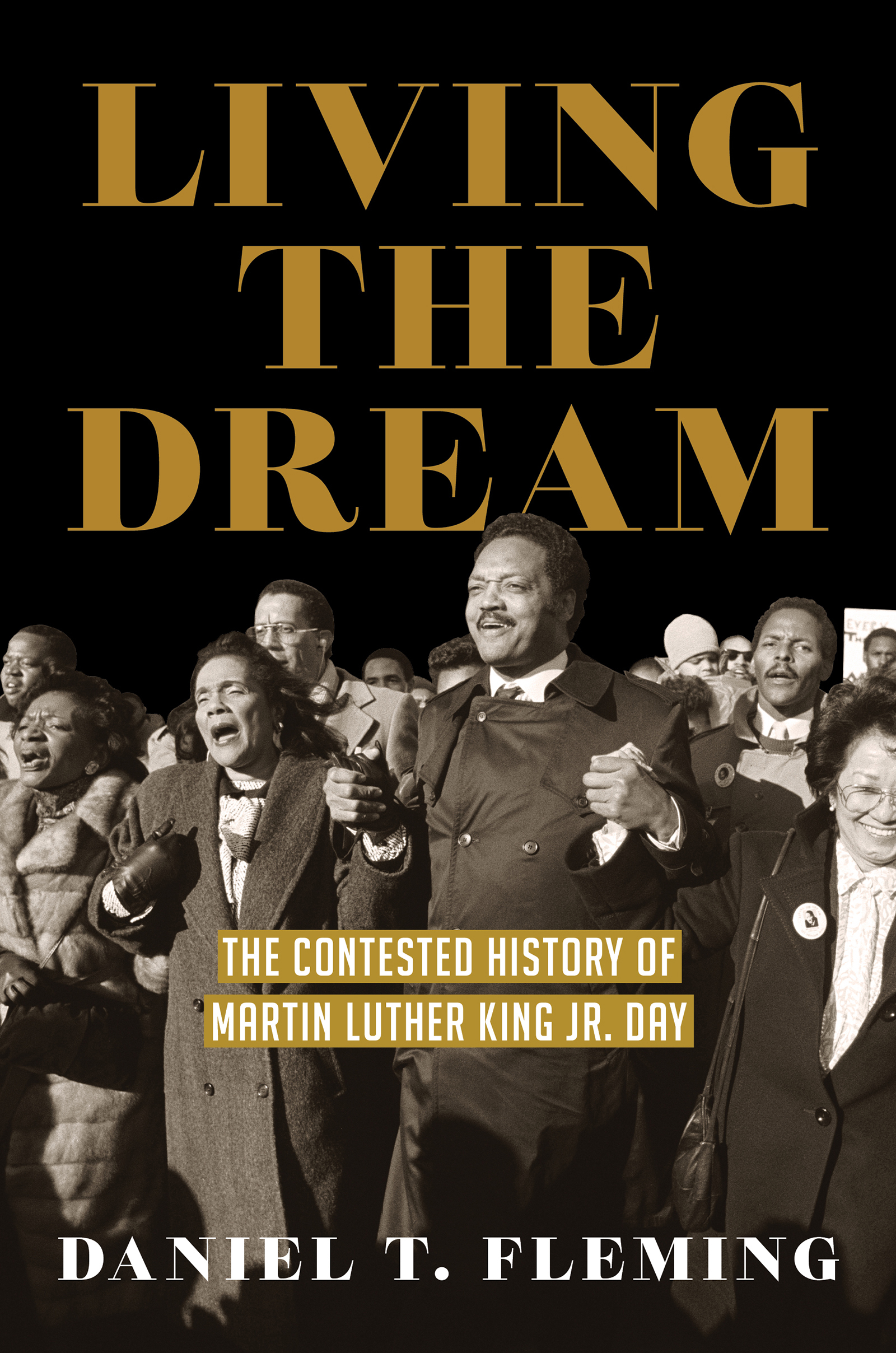

Living the Dream

Living the Dream

The Contested History of Martin Luther King Jr. Day

DANIEL T. FLEMING

The University of North Carolina PressChapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the John Hope Franklin Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2022 Daniel T. Fleming

All rights reserved

Set in Charis by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fleming, Daniel T. (Daniel Thomas), author.

Title: Living the dream : the contested history of Martin Luther King Jr. Day / Daniel T. Fleming.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021054809 | ISBN 9781469667812 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469667829 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Martin Luther King, Jr., DayHistory. | HolidaysUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC E185.97.K5 F583 2022 | DDC 394.261dc23/eng/20211214

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021054809

Jacket illustration: Left to right, Christine Farris, Coretta Scott King, Jesse Jackson, and Lupita Aquino Kashiwahara in Atlanta on January 19, 1987, at a parade for the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. AP Photo/Charles Kelly.

To Frances and Amory

Contents

Illustrations

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

Introduction

On January 20, 1986, half a million people looked on as the inaugural Martin Luther King Jr. Day parade wended down Peachtree Street and turned into Auburn Avenue, in downtown Atlanta. The celebrations did not end there.

Promoted with the slogan Living the Dream, the holidays reach extended across the nation.

Martin Luther King Jr.s legatees were, however, divided. Coretta Scott King and Andrew Young hoped that the holiday would keep Kings dream alive, inspiring Americans to complete his unfinished work. Thus, they worked to foster a mood of celebration and avoided overt politicking. Others, however, voiced concern over the commemorations tone. Disturbed by the festive atmosphere, Jesse Jackson and Julian Bond reminded Americans of Kings radical civil disobedience. Wyatt T. Walker warned against being oversentimental and romantic. They were concerned that the celebrations smoothed over Kings legacy, making him palatable for a nation unwilling to comprehend his critique, a nation unwilling to adopt his entire agenda as its own.

The holiday both canonized and deradicalized King. Since 1986, those seeking political and social reform in the United States have used it to advance their cause, despite its original apolitical tone. Those who have wanted to maintain the status quo have used it to argue that Kings dream has been fulfilled. In the process, Kings words have often been distorted beyond meaning, his virtues exaggerated and his deficiencies weaponized. Today, every effort to memorialize him is fraught with contradiction: to remember King risks forgetting his radicalism.

Coretta Scott King stood at the crux of her late husbands memorialization. Yet her example illustrates that the line between memorialization and activism is unclear. She demonstrated that fighting for a memorial is a form of activism.

The fight for the King holiday also constituted an act of resistance.

It is easy to find words of acclaim for King but difficult to find a similar praise for the King holiday. Scholars maintain that it fails to recall Kings radicalism.

The concern about King memorialization, as exemplified by the holiday, is that it typically portrays his agenda as complete. Dianne Nash, a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), feared that such exaltation of King would deter future generations from becoming activistseither because future injustices would not seem as dire as those in the past, or because youth would simply wait for the next great leader rather than start their own movement.

This book is not so much about King the person; rather, it is a study of how Americans memorialize him. At a time of fierce debate over the role of public commemorationwitness the rise of Black Lives Matter and the fall of Confederate statuesthis book examines one battle that presaged present debates about statues, flags, and Indigenous Peoples Day, and one that also presaged the instatement of Juneteenth as a federal holiday. The King holiday is part of this historic trajectory. Living the Dream considers several closely related questions: Why was King memorialized with the holiday? How do Americans portray King on the holiday? How have politicians, civil rights activists, and the King family used the holiday? Why has he been so intensely memorialized? And does civil rights memorialization undermine present-day activists fighting to complete Kings agenda? I seek to understand what the holiday reveals about race, class, gender, and collective memory in the United States, especially since Kings assassination.

Living the Dream argues that the United States chose King to commemorate as it considered him the most appropriate representative of an African American community that demanded recognition in the nations memorial landscape. Pressured by both working-class and middle-class African Americans and white liberals, Congress declared that King best represented the integrationist cause. He was a contemporary hero, rather than a distant historical figure; some who voted for the holiday had known him personally. Moreover, liberals and moderates, and some conservatives, thought King had transcended political partisanship. He could be co-opted by all.

Throughout its history, two competing aims have defined King Day: to celebrate and to protest. This book analyses the tension between these two aims, using the long-ago disbanded Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Holiday Commission as a lens through which to examine the holiday. Congress established the commission in 1984 to coordinate the first King Day and to organize a celebration with appeal to a broad spectrum of American society. Coretta Scott King chaired the organization, which included representatives and senators from Congress, presidential appointees, and selected leaders from businesses, unions, religious organizations, civil rights groups, and the entertainment industry.

Congress tasked the commission with inventing new traditions.

Although King holiday supporters belonged to a tradition of African Americans who wanted a national holiday to commemorate Black history,

Kings I Have a Dream speech provided early inspiration for the holiday, particularly during the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. Politicians of all persuasions used Kings dream, yet conservatives focused almost exclusively on this aspect of his legacy. Reagan used King in such a manner to promote individualism, capitalism, and conservative Christianity. Bush too prioritized a narrative that highlighted individual valor within the civil rights movement, as opposed to collective endeavor. When Kings former colleagues rejected the officially sanitized image of King the Dreamershorn of radicalismtheir dissatisfaction laid the foundation for reform. Following his election in 1992, Democrat Bill Clinton legislated for a day of service that shifted the holidays emphasis from the dream to volunteer community service, tilting King Day a little more toward activism than mere commemoration.