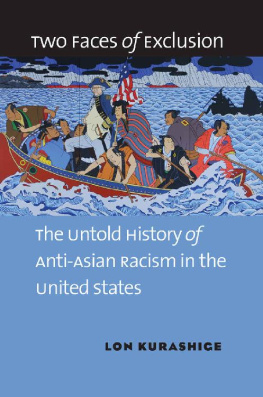

ALSO IN THE

History of Canada Series

Death or Victory: The Battle of Quebec

and the Birth of an Empire, by Dan Snow

The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight

and the Fight for Canada, by Ron Graham

The Destiny of Canada: Macdonald, Laurier,

and the Election of 1891, by Christopher Pennington

Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion

and the 1866 Battle That Made Canada, by Peter Vronsky

War in the St. Lawrence:

The Forgotten U-Boat Battles on Canadas Shores, by Roger Sarty

The Best Place to Be: Expo 67 and Its Time,

by John Lownsbrough

Death on Two Fronts: National Tragedies and the Fate

of Democracy in Newfoundland, 191434, by Sean Cadigan

Two Weeks in Quebec City: The Meeting That Made Canada,

by Christopher Moore

Ice and Water: Politics, Peoples, and the Arctic Council,

by John English

Julie F. Gilmour

General Editors

MARGARET MACMILLAN and ROBERT BOTHWELL

For Jeff

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF CANADA SERIES

Canada, the world agrees, is a success story. We should never make the mistake, though, of thinking that it was easy or foreordained. At crucial moments during Canadas history, challenges had to be faced and choices made. Certain roads were taken and others were not. Imagine a Canada, indeed imagine a North America, where the French and not the British had won the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Or imagine a world in which Canadians had decided to throw in their lot with the revolutionaries in the thirteen colonies.

This series looks at the making of Canada as an independent, self-governing nation. It includes works on key stages in the laying of the foundations, as well as on the crucial turning points between 1867 and the present that made the Canada we know today. It is about those defining moments when the course of Canadian history and the nature of Canada itself were oscillating. And it is about the human beings heroic, flawed, wise, foolish, complexwho had to make decisions without knowing what the consequences might be.

We begin the series with the European presence in the eighteenth centurya presence that continues to shape our society todayand conclude it with an exploration of the strategic importance of the Canadian Arctic. We look at how the mass movements of peoples, whether Loyalists in the eighteenth century or Asians at the start of the twentieth, have profoundly influenced the nature of Canada. We also look at battles and their aftermaths: the Plains of Abraham, the 1866 Fenian raids, the German submarines in the St. Lawrence River during World War II. Political crisesthe 1891 election that saw Sir John A. Macdonald battling Wilfrid Laurier; Pierre Trudeaus triumphant patriation of the Canadian Constitutionprovide rich moments of storytelling. So, too, do the Expo 67 celebrations, which marked a time of soaring optimism and gave Canadians new confidence in themselves.

We have chosen these critical turning points partly because they are good stories in themselves but also because they show what Canada was like at particularly important junctures in its history. And to tell them we have chosen Canadas best historians. Our authors are great storytellers who shine a spotlight on a different Canada, a Canada of the past, and illustrate links from then to now. We need to remember the roads that were takenand the ones that were not. Our goal is to help our readers understand how we got from that past to this present.

Margaret MacMillan

Warden at St. Antonys College, Oxford

Robert Bothwell

May Gluskin Chair of Canadian History

University of Toronto

INTRODUCTION

Few characters in Canadian history are viewed with such extremes of both respect and ridicule as William Lyon Mackenzie King. Alternately portrayed by historians as an anglophile, an American, a brilliant political mind, a naive spiritualist, a man of reason, and a racist, King was in fact all of these things, and it is this combination that makes him such a fascinating subject. In order to understand his later statecraft, we have to understand King, his world view, and his philosophy of government. To do this, it is necessary to examine his early professional life on its own terms before he became prime ministerin its international context, for King was an international man. He left his family home in Toronto for Chicago in the fall of 1896. While pursuing a master of arts under the supervision of eminent sociologist and political economist Thorstein Veblen, he also threw himself into the world of urban reform. He dabbled in settlement work at Jane Addamss Hull House for a time until the pressures of school drew him back to labour studies and his thesis. He was content in the United States and rather than returning to Canada after submitting his masters paper, he began pursuing a PhD at Harvard. However, King was not just a North American in his outlook. He was, after all, a Canadian subject of the British Crown, raised in the British Empire, and so when an opportunity arose to study at the London School of Economics, he accepted without reservation. He had therefore lived, worked, and studied in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain by the fall of 1899. He was not yet twenty-five years old.

King seems to have embodied the very struggles facing twentiethcentury Canada since both he and his country self-imagined at various times as important or insignificant, as American, British, or something else altogether. King and Canada were in the midst of huge changes in direction. In Kings case, the first decade of the century transformed him from an aspiring freelance civil servant into a member of Parliament and a fledgling diplomat with a recognized track record of successful international diplomacy. Canada was experiencing a shifting cultural landscape in which the importance of North American identities was growing clearer and the nations older transatlantic links with Great Britain were receding. This change was obscured by the formal political links that still bound Canada to Britain, but it was nevertheless a cause for concern among those who valued the British connection. These developments were amplified by the changing ethnic composition of Canada. The years before the First World War were extraordinary for the increase in immigration to Canadas west and the shift away from British and American settlers to immigrants from regions previously considered less desirable but now necessary for the economic goals of Canadian business. But immigrants could lower wages by expanding the workforce, a point of concern for labour unions, particularly if the immigrants were not white Europeans and thus did not even resemble the workers who faced what they perceived as unequal competitionfrom those whom they considered to be unequal people. Among these new immigrants were workers from China, Japan, and India who were often set apart for particular abuse by those who feared the rise of non-white immigration to Canada.

Fears of Asian immigration took a violent turn in Vancouver during a September 7, 1907, protest march. A crowd of demonstrators formed a mob, destroyed businesses in Vancouvers Chinese and Japanese neighbourhoods, and caused great distress to the communities and embarrassment for the Laurier government in Ottawa, which was called upon to mitigate the damage to Britains relations with both Japan and China. Fortunately for Laurier, he had the able young deputy minister of labour, W.L. Mackenzie Kinga natural conciliator itching to take on more responsibilityto carry out some of this work. King was quickly linked with these events and engulfed in the diplomacy that followed, and this experience influenced his thinking about Asia, Britain, the United States, Canada, and immigration for years to come. His international, political, reform-minded, and well-documented life gives us a fascinating window into Edwardian Canada and its place in the world. The riots were therefore both locally interesting and international in their implications, raising questions far beyond Vancouver and Ottawa about Canada and its diplomatic relationship with Britain and its allies.

Next page