Seaforth

WORLD NAVAL REVIEW

2017

Seaforth

WORLD NAVAL REVIEW

2017

Editor

CONRAD WATERS

Frontispiece: The futuristic new US Navy destroyer Zumwalt (DDG-1000) seen on trials in the North Atlantic in April 2016. Decisions to cease construction of the class at just three vessels mean that the class will be a rare sight on the worlds oceans but their innovative technology is likely to have a significant impact on future US Navy designs. (General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works)

Copyright Seaforth Publishing 2016

Plans John Jordan 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Seaforth Publishing

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley

S Yorkshire S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

Email

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP data record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-4738-9275-0

eISBN 978-1-4738-9277-4

Mobi ISBN 978-1-4738-9276-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Conrad Waters to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

CONTENTS

Mrityunjoy Mazumdar examines the navy of a country divided by 500 miles of water

Sren Nrby highlights how Denmarks maritime horizons have shifted since the Cold Wars end

Theodore Hughes-Riley assesses the recent direction one of the worlds most innovative naval forces

Tomohiko Tada provides a detailed description of Japans latest destroyer class

Guy Toremans explains the importance of the class to the Republic of Koreas broader naval ambitions

Edward Feege and Scott Truver analyse the importance of the US Navys radical surface combatant

David Hobbs undertakes his annual overview of recent developments in maritime air power.

Norman Friedman looks at a weapon that is generating renewed interest in the US Navy

Jan Ziolo expounds the need for preparation and speed when assisting a submarine in distress

Note on Tables: Tables are provided to give a broad indication of fleet sizes and other key information but should be regarded only as a general guide. For example, many published sources differ significantly on the principal particulars of ships, whilst even governmental information can be subject to contradiction. In general terms, the data contained in these tables is based on official information updated as of June 2016, supplemented by reference to a wide range of secondary and corporate sources, such as shipbuilder websites.

OVERVIEW

INTRODUCTION

A gainst danger, it is best to be prepared wrote the Ancient Greek storyteller Aesop in his fable of The Wild Boar and the Fox. The moral of the story seems particularly relevant at the present time as risks from both state-related tensions and nonstate-related violence continue to dominate the newspaper headlines. Indeed, there have been some indications over the past twelve months that governments worldwide are taking heed of the danger. Notably, defence reviews in countries as far apart as Australia and the United Kingdom have committed to bolstering spending to fund both refreshed and new capabilities.

An examination of the outcomes of the Australian and British defence reviews is instructive in terms of both their similarities and their differences. Interestingly, both commit to spending in the order of two per cent of national wealth as measured by gross domestic product (GDP) on national security. However, the Australian figure represents fulfilment of a previous pledge to increase spending that has already risen by some thirty per cent over the last decade, whilst the United Kingdoms commitment provides a floor to a long period of steady decline. Both reviews also make particular reference to the need to support an international rules-based order and the dangers posed by terrorism, as well as the rapidly expanding importance of cyber security. Expanding investment in these capabilities is a clear priority in the British review but the Australian white paper is more nuanced. With one eye to Chinas expansionist policies, much of Australias planned defence investment programme is meant to facilitate conventional operations against a state opponent, primarily in the Indo-Pacific region. One consequence of this is that the Australian review places much greater emphasis on expanding hard power naval capabilities.

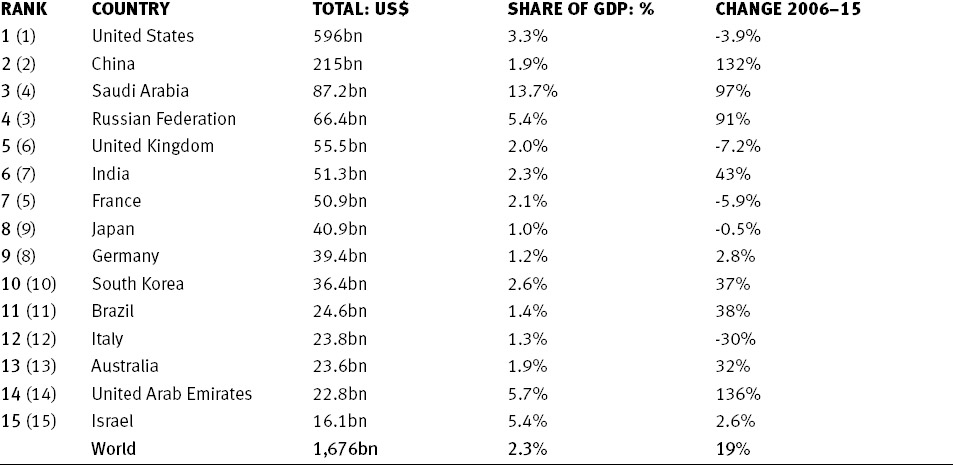

Table 1.0.1: COUNTRIES WITH HIGH NATIONAL DEFENCE EXPENDITURES 2015

Information from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/ The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database contains data on 172 countries over the period 1988-2015.

Notes:

Spending figures are at current prices and market exchange rates.

Figures for China and the UAE are estimates, with the UAE figure relating to 2014. Previous figures for China have been reduced downward from previous figures contained in the SIPRI database.

Data on military expenditure as a share of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) relates to GDP estimates from the IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2015.

Change is real terms change, i.e. adjusted for local inflation.

Figures in brackets reflect rank in 2014, revised for latest information.

The trend towards increasing defence spending is also reflected in Estimated global defence spending grew slightly to US$1,676bn in 2015: the first time since 2011 thar there has been a real-terms increase. Unsurprisingly, expenditure in the regional hotspots of Eastern Europe, Asia and to the extent there was data available the Middle East showed the greatest growth. However, there were also signs that recent declines in North America and Western Europe are coming to an end as the security environment becomes more complex. What the future holds is more difficult to discern. The share of national wealth expended on the military has arguably reached unsustainably high levels in a number of countries. This is particularly so for those, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, that have economies heavily exposed to the decline in world oil prices. As a result, both countries currently third and fourth in the list of big spenders are expected to see reduced defence budgets in 2016.

Given, particularly, Russias difficult situation, it is easy to conclude that the recent willingness exhibited by many Western European countries to spend more on their militaries in response to Russian adventurism in Ukraine and elsewhere will soon be reversed as risk perceptions are adjusted downwards. Certainly, Russias navy continues to pay a heavy price for its intervention in the Crimea and the Donbass, most notably through the impact of sanctions on its modernisation plans. Its French-built Mistral class amphibious assault ships now fly the Egyptian flag, whilst progress on important surface programmes continue to be slowed by lack of components. In spite of this backdrop, it appears that many countries have undertaken a fundamental re-appraisal of the risks they face perhaps for the first time since the end of the Cold War and have become concerned by the result. There appears to be a broad consensus that higher levels of spending will be sustained for the rest of the decade.