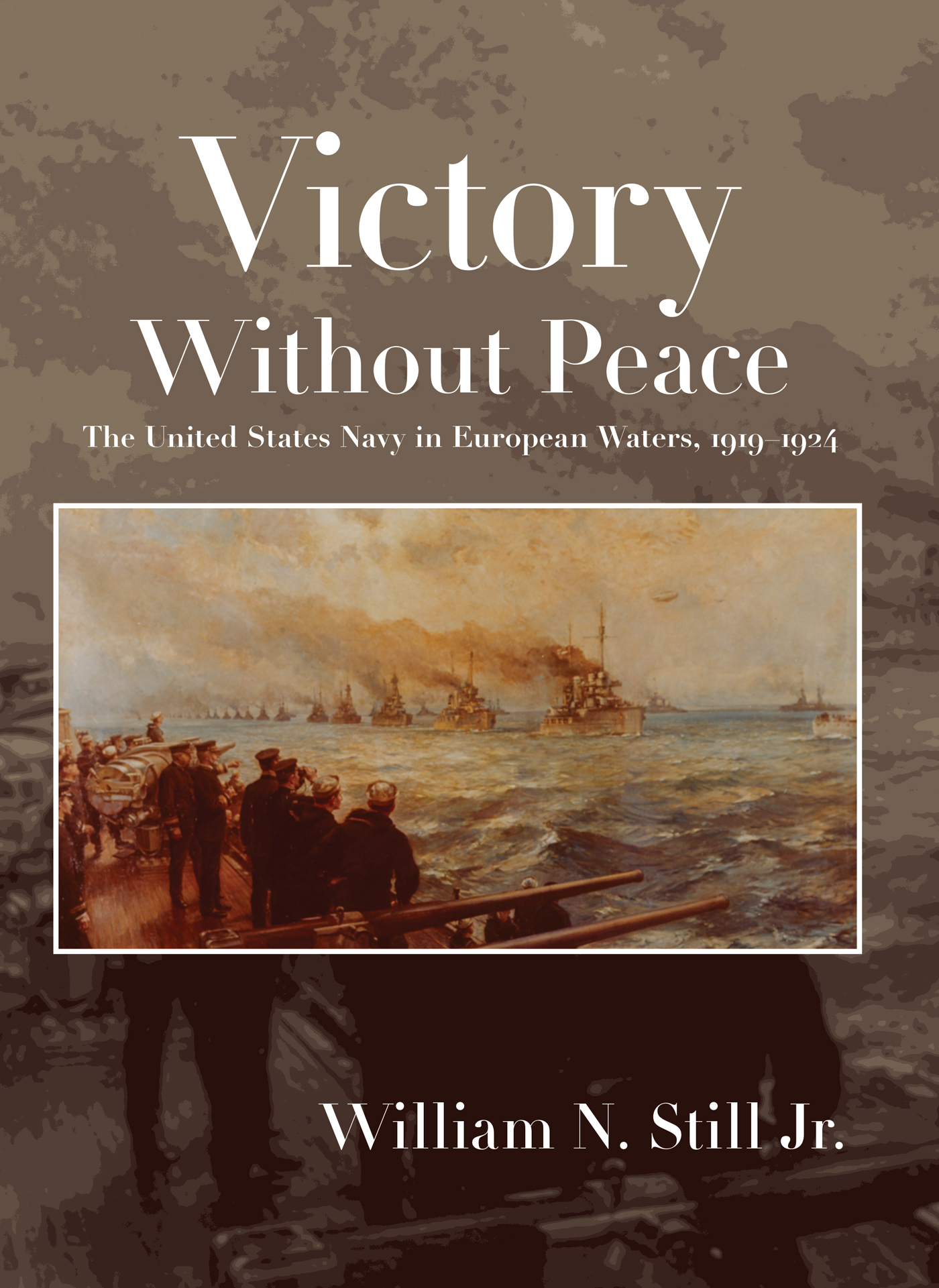

Victory

Without Peace

Titles in the series:

Progressives in Navy Blue: Maritime Strategy, American Empire, and the Transformation of U.S. Naval Identity, 18731898

Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 18981945

Studies in Naval History and Sea Power

Christopher M. Bell and James C. Bradford, editors

Studies in Naval History and Sea Power advances our understanding of sea power and its role in global security by publishing significant new scholarship on navies and naval affairs. The series presents specialists in naval history, as well as students of sea power, with works that cover the role of the worlds naval powers, from the ancient world to the navies and coast guards of today. The works in Studies in Naval History and Sea Power examine all aspects of navies and conflict at sea, including naval operations, strategy, and tactics, as well as the intersections of sea power and diplomacy, navies and technology, sea services and civilian societies, and the financing and administration of seagoing military forces.

Victory

Without Peace

The United States Navy in European Waters, 19191924

William N. Still Jr.

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2018 by William N. Still

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

978-1-68247-014-5 (hardcover)

978-1-68247-015-2 (eBook)

All photos are from the U.S. Naval Institute photo archive.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

Printed in the United States of America.

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 189 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A fter World War I the Navy considered Europe to be a backwater and overwhelmingly emphasized the Pacific instead. The Battle Fleet would be transferred to the Pacific in 1919, but even with the Armistice the year before, Admiral William Benson, the Chief of Naval Operations, was determined to get the naval vessels deployed in European waters home as quickly as possible. Doing so, however, proved to be impossible. The United States assumed responsibilities that kept American warships in European waters and the Near East for several more years.

The deliberations and decisions of the peace conference in Paris were key factors in U.S. naval operations in European waters in postwar Europe and the Near East. The United States would withdraw from the conference in December 1919, but the Navys commitment to the distant missions it had undertaken would continue. James Cable in his book Gunboat Diplomacy points out that coercive diplomacy, an alternate to war, is intended to acquire objectives from another state. Showing the flag, as another writer points out, is nothing more than a gentle reminder of the presence of the naval force in question. This volume ends in 1924 with the withdrawal of U.S. naval vessels from Near Eastern waters and in general the return to the normal peacetime activities of showing the flag.

Books have histories too. This is the third volume of a study of the U.S. Navy in European waters from the end of the American Civil War until the station was abandoned in 1929. The first volume, American Sea Power in the Old World, covered the period from 1865 to 1917; the second, Crisis at Sea, concerned the Navys involvement in World War I. This volume addresses the operations of U.S. Naval Forces in European Waters from 1919 to 1924. Like the first volume, Victory without Peace concentrates on naval and diplomatic activities and the protection of American citizens and property. It also, however, emphasizes the important role that the Navy played in large-scale humanitarian missions, a kind of activity new to the service. The years 191924 were marked by revolution, civil war, international conflict, and other upheavals caused by the just-ended world war, and the U.S. Navy found itself intimately involved in this turmoil. The Navy was especially caught up in the Near East (or Middle East, as it is often called), and at one time I planned to write a study of the Navys operations in that region. Fortunately, Bob Shenk has now covered that ground in his excellent Americas Black Sea Fleet (2017). I have included the Navys involvement in the Near East in my study, avoiding duplicating with Bobs work where possible. I have agreed with some of his conclusions and disagreed with others. Inevitably we used many of the same sources, but surprisingly he had sources of which I was not aware and I had some that he did not cite. Considering the topic, I suspect that there are sources known to neither of us.

Military terminology has changed with the agesas relating to weapons, weapon systems and technology, tactics, and even strategy. Strategic bombing, ground zero, and more recently embedded are examples. The terms mobilization and demobilization were introduced in the American military in World War I. This book examines naval demobilization in Europe extensivelymaterial that is, admittedly, boring but has not been studied before and is, I think, important. This is not only the first conflict in which the U.S. military experienced coalition warfare but also the first in which it deployed hundreds of thousands of men abroad to fight and then brought them home. Demobilization of the U.S. Army, particularly the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), which went to Europe during the war, has received considerable attention. Industrial demobilization and its effect on the American economy have also attracted historians. Naval demobilization not as complex as that of the AEF, but it toowith hundreds of vessels, bases, and air stations in the war zonewas extensive. Even without precedents to draw upon, it was successfully accomplished. Nonetheless, it has generally been ignored.

It is hard to believe that I began research for these three volumes on the U.S. Navy in European waters more than forty years ago. Much of it was done when I was the Secretary of the Navys Scholar in Residence at the Navy Yard, 198990. I continued research for the present volume afterward. In those decades historical research and writing have changed dramatically. My earliest writing was on a typewriter, a fact that at times I find hard to believe. Note taking was primarily by hand; copying was expensive. Progress came in time, of course, with microfilm and other copying processes; the National Archives and other repositories microfilmed thousands of documents and manuscripts. There were few personal computers until the 1980s, but eventually computers would revolutionize research and writing. Repositories have digitized their collections, making them accessible without having actually to visit them.

Despite these changes and others taking place as I worked, I decided to cite documents and manuscripts archivally, in the media in which I examined them, not as they might be cited today. When writing

Next page

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992