Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

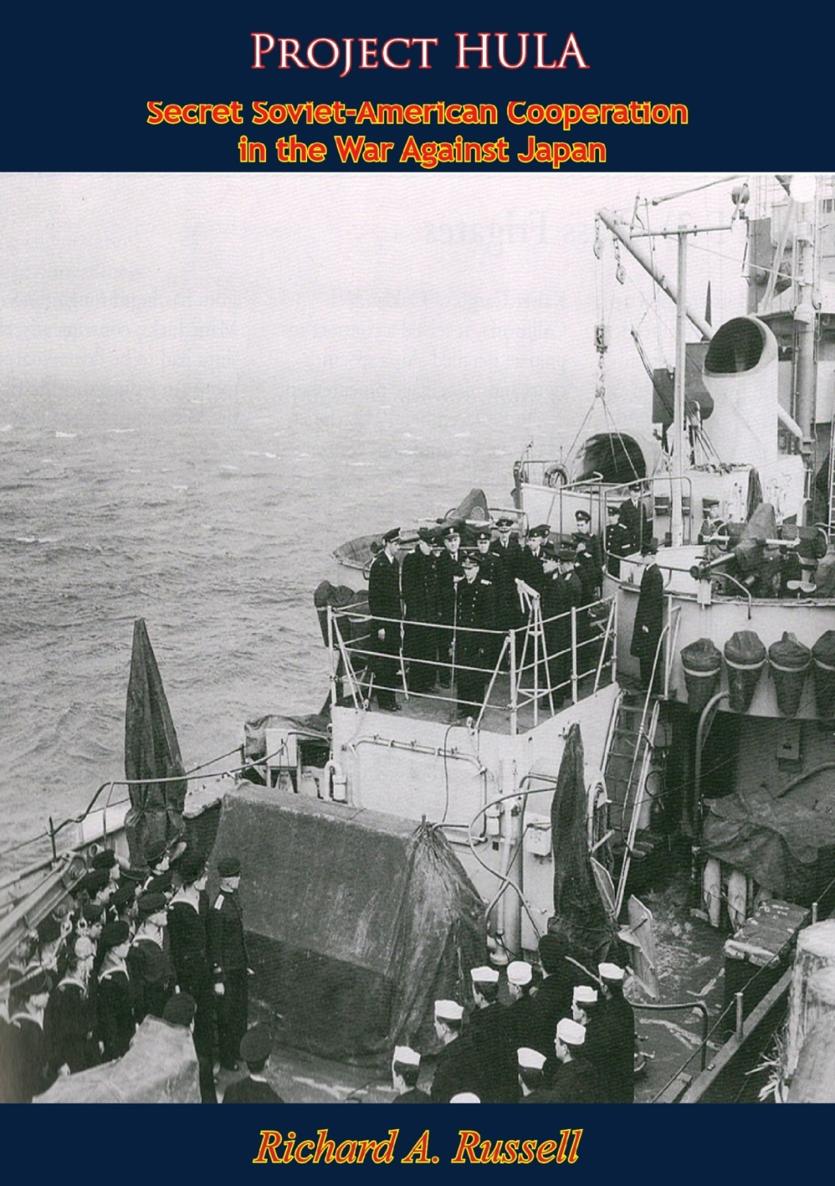

PROJECT HULA

SECRET SOVIET-AMERICAN COOPERATION

IN THE WAR AGAINST JAPAN

BY

RICHARD A. RUSSELL

The visitors included many officers whom the United States Navy would be pleased to have, and...the visiting enlisted men were well disciplined, energetic and extraordinarily hard-working, and often the equal of American personnel....The visitors demonstrably possess the essentials of a major naval power.

Captain William S. Maxwell to

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King

27 September 1945

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Secretary of the Navys Advisory Subcommittee on Naval History

Dr. David Alan Rosenberg, Chair

CDR Wesley A. Brown, CEC, USN (Ret.)

Dr. Frank G. Burke

Mr. J. Revell Carr

VADM Robert F. Dunn, USN (Ret.)

VADM George W. Emery, USN (Ret.)

Dr. Jose-Marie Griffiths

Dr. Beverly Schreiber Jacoby

Mr. David E. Kendall

Mr. Harry C. McPherson, Jr.

The Honorable G. V. Montgomery

Dr. James R. Reckner

Dr. William N. Still, Jr.

ADM William O. Studeman, USN (Ret.)

Ms. Virginia S. Wood

DEDICATION

For Marie

and in memory of my father-in-law ,

Bruno J. Martini (1935-1996)

Foreword

This study is the fourth in the Naval Historical Centers series, The U.S. Navy in the Modern World, that aims to acquaint naval officers, sailors, and other readers with the U.S. Navys unique contribution to national security, economic prosperity, and global presence in the contemporary period.

Starting in the Second World War, the United States assumed the leadership of major multinational politico-military coalitions, first to destroy fascism and later to thwart the spread of communism. Military assistance programs, in which the American armed services helped their foreign counterparts to help defend themselves, served a vital if unheralded role in the common defense. Such programs, so familiar today, originated with the timely creation of the lend-lease program of World War II.

This booklet, based on original materials culled from archives in the United States and in the Russian Federation, treats a little known aspect of lend-lease and of Soviet-American relations at the end of the Second World War. The author, Richard A. Russell, has cultivated singularly productive relations with prominent historians, archivists, and naval officers in Russia. His tireless efforts to obtain access to Russian naval archives and to introduce their materials into the writing of recent American history will revise how historians approach working on the naval aspects of the Soviet-American alliance in World War II and the Cold War at sea.

In addition to Mr. Russells efforts, I am pleased to acknowledge those individuals who contributed to this publication, including Dr. Edward J. Marolda, our Senior Historian and founder of the series; Dr. Gary E. Weir, head of the Contemporary History Branch and editor of the series; many of the professional staff of the Naval Historical Center, especially the members of the Naval Aviation News Branch; and the other scholars and professionals at institutions in the United States and the Russian Federation. Finally, I am grateful to the U.S. Navys World War II Commemorative Committee for their help in producing this publication.

The views expressed are those of Richard A. Russell alone and not necessarily those of the Department of the Navy or any other agency of the U.S. government.

William S. Dudley

Director of Naval History

Introduction

In the 1930s, the potential for cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union to restrain Japanone of the unspoken objects behind Washingtons decision to recognize the Moscow regime in 1933did not evolve into any concrete strategy beyond wistful ideas and a few hollow gestures. By the end of the decade, both countries adopted independent policies toward Japanese aggression in Asia.

In 1939, Soviet forces won a bloody border war against Japan. Japanese attention then turned toward the Asian possessions of the colonial powers. At the same time, in Europe, the Soviet Union and the Western democracies failed to reach an agreement on how to deal with Germanys threat to the peace. To the dismay of the West, Soviet leader Josef Stalin and German dictator Adolf Hitler completed the infamous Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, which included a scheme to divide Poland between them. Within a week, Germany attacked Poland, which prompted Great Britain and France to declare war on Germany, igniting World War II.

The Soviet Union and United States stayed out of the growing conflict until June and December 1941, respectively, when Germany attacked the Soviet Union and Japan attacked the United States. When Germany and Italy then declared war on the United States, the alliance between the U.S. and the USSR, which appeared improbable only months before, was forged. In Asia, however, Japan and the Soviet Union managed to preserve, in the words of historian George Alexander Lensen, their strange neutrality. By December 1941, the staggering success of the German attack in European Russia left Stalin with little means and no desire to open the two-front war against Japan sought by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Japans subsequent acquiescence to the movement of vital lend-lease supplies to the Soviet Far East via the North Pacific ensured Soviet neutrality in Asia while the European war raged.

This situation prevailed until 1945, with a regular ebb and flow of hope and frustration on the U.S. side, which sought basing rights for heavy bombers in Siberia and suffered concern for the security of the lend-lease route. At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, however, the United States secured Soviet entry into the war against Japan by pledging to provide military support and several important territorial considerations, including turning over the Kuril Islands to the Soviet Union.

In the spring and summer of 1945, a special detachment of the United States Navy trained some 12,000 Russian officers and men in the handling of naval vessels scheduled for transfer to the Soviet Pacific Ocean Fleet under the lend-lease program. Project HULA required American and Russian sailors to work side by side in the largest and most ambitious transfer program of World War II. Its unique purpose was to equip and train Soviet amphibious forces for the climactic fight against Japan.