Politics and Culture in Modern America

Series Editors: Glenda Gilmore, Michael Kazin, Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

Copyright 2008 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-4070-2

ISBN-10: 0-8122-4070-7

Preface

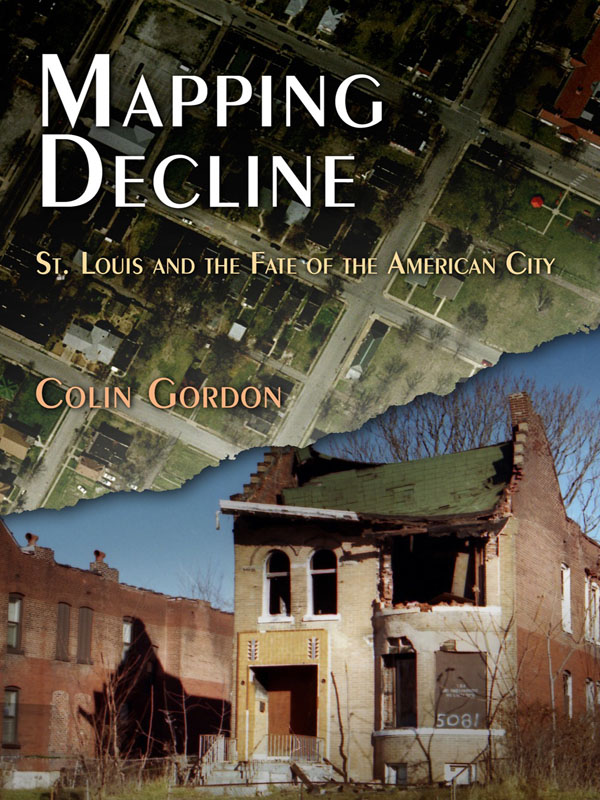

In the summer of 2002, I attended an academic conference in St. Louis. Upon arrival at the hotel, I realized that the conference was not really in St. Louis but in Clayton, an inner suburb that had reinvented itself as a corporate park. St. Louis, as I discovered on my first foray east into the city, seemed to consist largely of abandoned houses and boarded-up storefrontsinterrupted, only a few blocks from the Mississippi, by haphazard commercial redevelopment. This was a bad first impression (my route took me through the most neglected neighborhoods), but it stuck.

That summer, my colleague Peter Fisher and I received seed funding to begin work on a history of economic development policies in the United States, part of which would be used to learn the ropes of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping, part of which would be used to delve into the historical meaning of blight in urban public policy. As we wrestled with the mapping, and particularly the challenge of digitizing historical sources, it became increasingly clear that we needed to start with a local case study. And, as we sorted through the legal and political history of blight, many of the most egregious cases (that is, cases that stretched the definition of blight in order to create tax breaks or subsidies) that cropped up were in the St. Louis suburbs.

So St. Louis was an important case but an understudied one. But the first step into the archives made one thing clear: the key to the story was not just the perfidy or futility of local urban renewal efforts, but the conditions that made such measures necessary. This pushed the research in new directions and earlier into the twentieth century. What began as a place to start a national history of local economic development policies had become a research project of its own. In some respects, this would be a conventional case study of urban declinethe St. Louis chapter of a story told so masterfully in other settings (Arnold Hirsch on Chicago, Tom Sugrue on Detroit). In other respects, it was an opportunity to tell that story in a different way, employing the visual and explanatory power of GIS mapping (using census and archival data) to underscore the causal and consequential dimensions of the urban crisis in greater St. Louis and beyond.

While the archival record was complicatedspanning two states, twelve counties, and over one hundred local jurisdictionsit also proved extraordinarily rich. One of the nations leading urban planning firms, Harland Bartholomew and Associates, did almost all of the substantive planning and zoning on the Missouri side and left behind (at Washington University) an expansive documentary and cartographic record. The Missouri State Archives maintain extensive case and evidentiary records of most of the states key land-use cases. And other local archivesincluding the Western Historical Manuscripts Collection and Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, the Missouri Historical Society, the St. Louis Public Library, and the St. Louis Assessorfilled in many important gaps. I owe these institutions and their archival staffs many thanks for their help and their patience.

A novice in both local history and GIS mapping, I learned not to be shy about asking for help. Alan Peters gave me a crash course in GIS and was quick to help whenever I was perplexed by hardware, software, data, or all three. Petra Noble at the National Historic Geographic Information System (NHGIS) Center in Minneapolis helped with census data. Ben Earnhart magically transformed the old ICSPR census files on St. Louis into a GIS-friendly format. Heather MacDonald helped me to access and understand mortgage disclosure data. Mary McInroy and John Elson proved invaluable guides to map and data collections at the University of Iowa Libraries. I am also most grateful to those willing to share data or shapefiles generated in the course of their own work or research; special thanks to Charles Kindleberger (St. Louis Community Development Administration), Richard Biggs (U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Missouri), Thomas Luce (Amergis), Gary Mook (East-West Gateway Coordinating Council), Dan Backowski (Ballwin), Pamela Burdt (Town and Country), Ken Yost (Kirkwood), Linda Roberts (Fenton), Frank Hill (University City), Steve Duncan (Eureka), and Matthew Brandmeyer (Creve Coeur).

I have learned a great deal from the work of others. Much of this debt is documented in the footnotes, but some is not. For conversations and correspondence and encouraging words, I thank Robert Fogelson, Amy Hillier, Meg Jacobs, Dennis Judd, Ira Katznelson, Jennifer Klein, Greg Leroy, Maire Murphy, Dave Robertson, Mark Rose, Tom Sugrue, Todd Swanstrom, and Josh Whitehead. Special thanks to Peter Fisher and Joel Rogers who, in different ways, taught me the important questions and pointed me toward the answers. My colleagues at Iowa provided a warm and collegial environment. The department staff provided invaluable assistanceeven on those days I took over the conference room to color maps. And my friends and colleagues at the Iowa Policy Project and the Economic Analysis Research Network provided the persistent and pointed reminder that, as the novelist Graham Swift put it, history begins only at the point where things go wrong; history is born only with trouble, with perplexity, with regret.

This project received financial support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Iowa Obermann Center, the Robert Seilor Fellowship of the Missouri State Archives, the University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and the University of Iowa Office of the Vice President for Research. At the Press, thanks to Bob Lockhart for his support (and for not blinking when I sent him a manuscript with 72 color maps), to Chris Hu for attention to the details, and to Alison Anderson for shepherding the final stages.