This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2021 by Mary N. Taylor

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2021

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-05781-5 (hard cover)

ISBN 978-0-253-05783-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-05782-2 (web PDF)

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction: The Aesthetic Nation

oneMaking the Nation-State in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Hungary

twoWhat Kind of Nation? Folk National Cultivation in the Interwar Period

threeSocialist Cultural Management, Civic Cultivation, and Associational Life in Late Socialism

fourThe Tnchz Revolution: Reviving Folk Dance as Social Dance

fiveFolk Dance as Mother Tongue: National Conduct and the Production of Collective Memory

sixSocialist State Formation, Tnchz Frameworks of Sense, and the Origins of the Postsocialist Cultural Turn

sevenThe Place of Heritagization: Culture Talk amid Shifting Property and Citizenship Regimes

Conclusion

Bibliography

Index

I WRITE THESE WORDS AS a powerful movement for Black lives manifests itself on streets across the United States and parts of Europe, a movement that is pushing to change policies in New York City, where I live, sparked by the callous murder of a Black man by police in a country spottily locked down due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This movement honors Black lives and emphasizes the racist structures and (un)consciousness that have been normalized in my country of citizenship since its foundation. The child of an interracially adoptive family, a social experiment of sorts, I have always had difficulty fitting within the absolute boundaries that define identity at home. I thank my parents, Bincy and Snowden Taylor, for starting me on this journey of exploring how racialized and ethnonational affects are crafted and how citizens are cultivated, a journey from which this book has emerged.

A long time coming, this book has only materialized due to the encouragement of friends and comrades in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, many of whom I met through my work with LeftEast and its summer schools, who convinced me of the value of the content of my 2008 dissertation. This was despite my status in the academy as one of the many PhD holders who have not found secure work as a professor. Along with these supporters, I am committed to understanding the world toward the end of changing it. I hope this book contributes to the struggle to understand and undermine the workings of ethnonationalism and racial capitalism. While I am indebted to many people for their help in making this book come to life, any mistakes and weaknesses are mine alone. Among the weaknesses are a few incomplete references. My eagerness to take notes from sources in archives and libraries when in Hungary sometimes got in the way of noting complete reference information. I have tried to fix this the best I can.

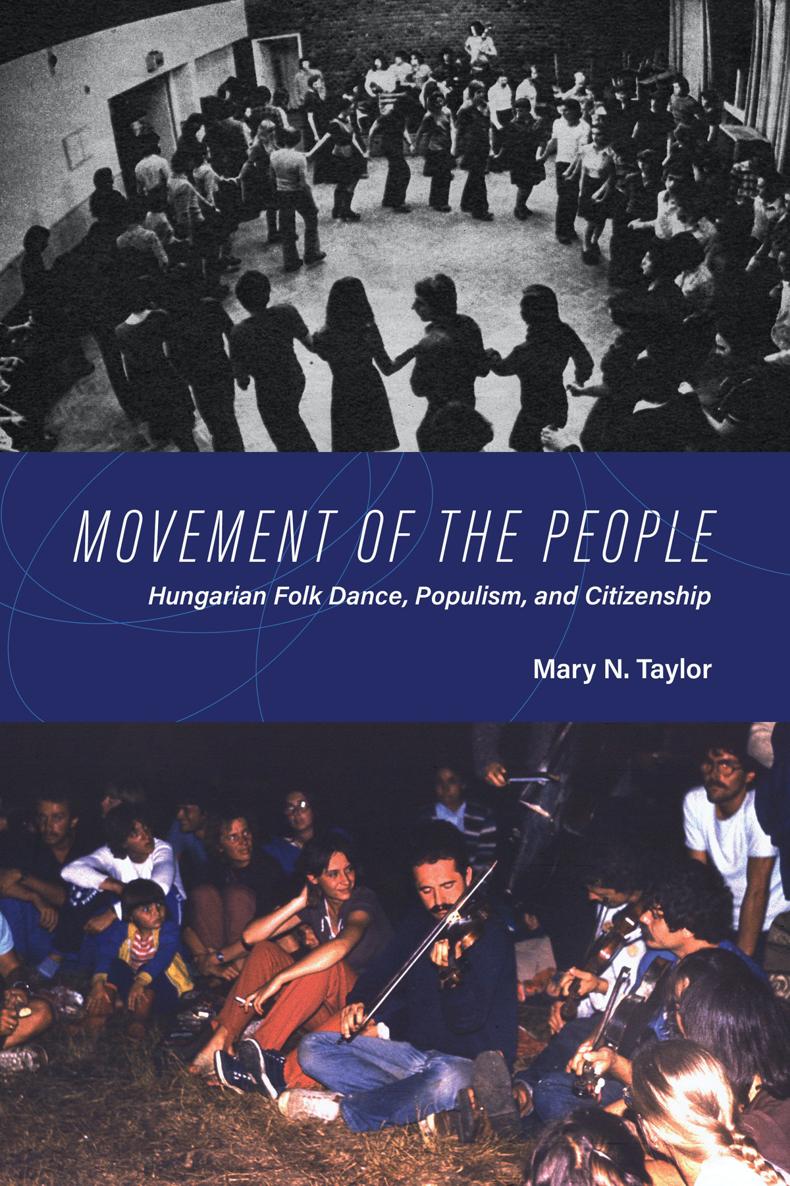

I am indebted to so many people, alive and passed on, whose knowledge has informed this book. First and foremost, I must thank the countless tnchz-goers, musicians, dancers, and organizers who welcomed me into their world, shared food and drink with me, talked and argued with me, drove me around Transylvania, and taught me to dance. Thank you, most especially, gnes Bly and Zoli Lgradi. I am also deeply grateful to the many Transylvanian villagers who hosted me and shared their thoughts and feelings and homes. I owe thanks to the late Bla Halmos, and to Seb Ferenc, Lszlo Kelemen, and the many others at Hagyomnyok Hza who helped me with my research in various ways. Kristina Nagy and Tibor Vasvry-Toth, librarians at the Martin Mdiatr, as well as the librarians at Magyar Mveldsi Intzet and the Selyemgombolyt library deserve special mention. Thank you to the ethnographers at the Ethnographic Research Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences who engaged me when I was a guest there, and since then, foremost among them gnes Flemile, my teacher, advisor, and critic since 2000, and Mihly Srkny, who pushed me in front of a podium at the Institute. Ivn Vitnyi and Lszlo Borsnyi also contributed to my research process in invaluable ways. I owe a great debt to the good friends and family in Hungary who hosted and fed me, laughed with and at me, and commented on my impressions in 20045, most notably Gbor Valcz, Csaba Ldi, Edit Garai, bel Kves, Zsuzsa Fehr, Sndor Striker, and Bea Vidacs.

As this project began during my PhD studies, I want to acknowledge my committee members, Gerald Creed, David Harvey, and Jane Schneider, who offered valuable comments that shaped the research from which this book is crafted. I also wish to thank Ellen DeRiso, Michael Blim, Vincent Crapanzano, Katherine Verdery, Donald Robotham, Talal Asad, Chris Hann, and Shirley Lindenbaum and students in the writing group she facilitated. I am grateful to the Fulbright Program and the Hungarian-American Commission for Educational Exchange in Budapest for funding my 20045 research and to the Anthropology Department at the City University of New York for a travel grant.

As I wrestled with the text that you have before you now, I had the enduring support of my colleagues at the Center for Place Culture and Politics (CPCP): Ruthie Gilmore, David Harvey, and Peter Hitchcock. The annual CPCP seminars and conferences have been spaces of rich knowledge production, rigorous analysis, and experiments with solidarity, and I can only hope that this book reflects a small part of what I have learned there. Thanks to gnes Gagyi, my dissertation was read by with many young Hungarian scholars and scholar activists. Among them are Gerg Pulay, Eszter Gyrgy, Csaba Tibor-Tth, and Marton Szarvas, who met to give me valuable feedback in Budapest just days after Indiana University Press offered me a contract. I wish to thank Johanna Bockman and Gerald Creed for their careful comments and for pushing me toward submission and the two anonymous reviewers of my manuscript for their extensive comments. I am indebted to Piroska Nagy and Matt Frost, who generously shared their photographs, to all the photographers whose work I accessed through open source means, and to Barbara Szecsdi, who helped me locate images at the Folklore Documentation Library and Archive at the Hungarian Heritage House. Thanks to Zord Heuz for digitizing my Hi8 footage. I am eternally grateful to the entire team at IUP that saw me through all of the stages of bringing this book to light. Special thanks to Jennika Baines, to the scrupulous copyediting team who worked behind the scenes and to Jeremy Rayner for making the index.