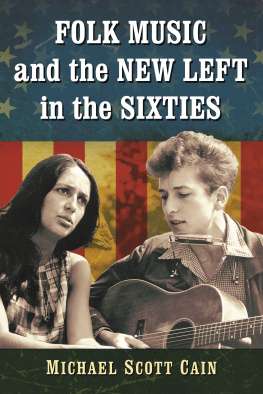

Folk Music and the New Left in the Sixties

MICHAEL SCOTT CAIN

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

The author died on January 30, 2018, after completing the manuscript for this book.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3595-8

2019 Helene Toney Cain. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Joan Baez and Bob Dylan performing at the Civil Rights March in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963 (National Archives)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

We were young, we were reckless, arrogant, silly, headstrong but we were right.Abbie Hoffman

Folk music has pretty powerful medicine for changing your heart.Peter Yarrow

Preface

In January of 2017, as the Trump administration was getting started and the nation was erupting in reaction to his actions, the Washington Post published a column by Richard Just arguing that the music of the sixties folk singer Phil Ochs is more important today than ever. In the column Just stated, [A]s we enter the Trump era, and as a new mass protest movement begins to take shape, his music would be worthy of a revival.

At the time Just wrote, Trump had been president for only a few weeks and already there had been daily protests all across the nation. The University of California at Berkeley was once again exploding with protestors, with reports of violence and riots on campus. As the New York Times reported, the triggering action was the university Republican Clubs scheduling of a speech by Milo Yiannopoulis, a reporter for the right-wing website Breitbart and a white supremacist provocateur. Yiannopoulis is no ordinary conservative. His speeches frequently take a hard turn toward hate speech (in a talk at the University of Wisconsin he ridiculed a transgender student by name) and he often attacks other races. Controversy tracks him like a heat-seeking missile.

At Berkeley he planned to publicly out transgender students.

Berkeley students claimed that the violent people were not students but community members who came to the campus to run wild. On CNN, former United States secretary of labor and current Berkeley professor Robert Reich repeated a never-confirmed rumor that the rioters were bought and paid for right-wing activistshired to come to the event and stir up trouble. Whoever they were and wherever they came from, school or community, they were there and the campus found itself divided and fighting, just as it had been back in the Free Speech days of the early sixties.

It was then that the calls like the one Richard Just issued for a revival of Phil Ochs music began going out. Many writers published pieces declaring that Phil Ochs was needed again. Peter Stone Brown published an article in Counterpunch asking, Where Is Phil Ochs When We Really Need Him? In it, Brown says, Considering the state of America in the 21st Century, I think about Phil Ochs a lot and what he mightve written and sung about whats going on now. Where is Phil Ochs when we need him?

So, why is the music of Phil Ochsand, I would argue, folk music in generalso badly needed today? Rob Young explains it this way:

Interest in folk music and other buried aspects of national culture tends to be reawakened at moments when theres a perceived danger of things being lost for ever. Successive folk revivals of the 20th century drew their impetus equally from the two historical landmarks that most permeate the British collective unconscious: the industrial revolution and the first world war. In the late 1960s and early 70s, fear of annihilation, technological progress and a vision of alternative societies filtered through popular and underground culture, conspiring to promote the ideal of getting back to the garden.

Among a large segment of the population, Trumps election meant a dramatic move away from the garden that was the Obama administration. Folk music is a means of understanding these seismic cultural shifts that are continually happening and helping to create an alternative. These are songs that explain the tenor of the times to their audiences.

Why Folk Music and Why Now?

To explain why people perceive a fresh need for folk music in our political realm we should probably understand the circumstances that brought our present situation into existence. Like so much of our culture today the phenomenon has its roots in the sixties. At that time, drawing on the roots their forerunners planted in the union movements of the thirties and forties, folk singersfollowing in the path of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and the Almanac Singers, and the Weaversartists of a new generation, stepped forward and created their own response to the world in which they found themselves. Foremost among these artists who mixed music and radical politics were Phil Ochs, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, Carolyn Hester, and Bob Dylan. Although the work of other artists will be considered, this book will primarily utilize those five as examples. These are the singer-songwriters who stepped forward and helped change America. This book aims to show why and how it happened and what that early activism means to us as we go forward.

Introduction

My own few attempts at activism were centered around folk music. If I attended a rally chances are a major reason was to see the artists performing, and while I had a mental image of myself as an activist I was never truly comfortable in that role. My own few pitiful efforts at creating radical change began when I was living in Fort Lauderdale, going to college at Florida Atlantic University. One morning I drove over to see a friend, Barry, a red-headed, freckled-faced classmate of mineanother English major in love with Elizabethan drama. We often got together to swap notes. Barry was the only white kid I knew who was rooming with an African-American guy in a minority neighborhood.

To get to the apartment they shared you had to drive down Sunrise Boulevard, beyond the huge, booming new shopping mall that housed Jordan Marsh, Burdines, and all the other upscale department stores and past Hugh Taylor Birch State Park. Then you kept driving, on beyond Holiday Park, where Chris Everts father was the tennis pro and the officials displayed a completely restored World War II fighter plane on the playground. You could crawl around on the plane and even climb into it. The cockpit was a popular makeout spot. Before she fell in love with cats and began populating her novels with them, Rita Mae Brown described in Rubyfruit Jungle how shed lost her virginity in that airplane.

Youd keep on going down Sunrise until you came to the Sunrise Drive-in with its attached permanent flea market, billed as the biggest in the world and with its own circus and drive-in movie. There were country music concerts on the stage, with stars like Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard playing there when they toured south Florida. Kevin Welch did a TV special from that stage. Beyond the worlds largest flea market you turned north and drove a couple of blocks until you ran out of paved road. When you came to the dirt roads you had entered the black section of the city. It was like going back in time to the Dust Bowl days. The dirt roads, the rust on the foundation blocks of the concrete and stucco structuresCBS houses, they were calledthe clothes drying in the sun in the yards, the corner food shops featuring old stock and inflated prices. It was all reminiscent of bad movies. It was

Next page