Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Jeff Wallenfeldt, Manager, Geography and History

Rosen Educational Services

Shalini Saxena: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Karen Huang: Photo Researcher

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Jeff Wallenfeldt

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sounds of rebellion: music in the 1960s/edited by Jeff Wallenfeldt.1st ed.

p. cm.(Popular music through the decades)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-913-9 (eBook)

1. Popular music1961-1970History and criticism. I. Wallenfeldt, Jeffrey H.

ML3470.S636 2013

781.6409'046dc23

2012020472

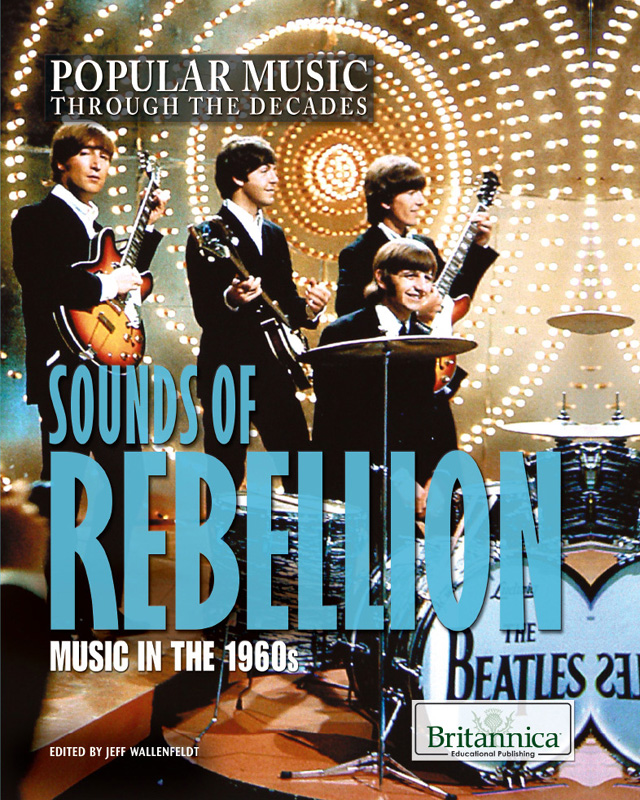

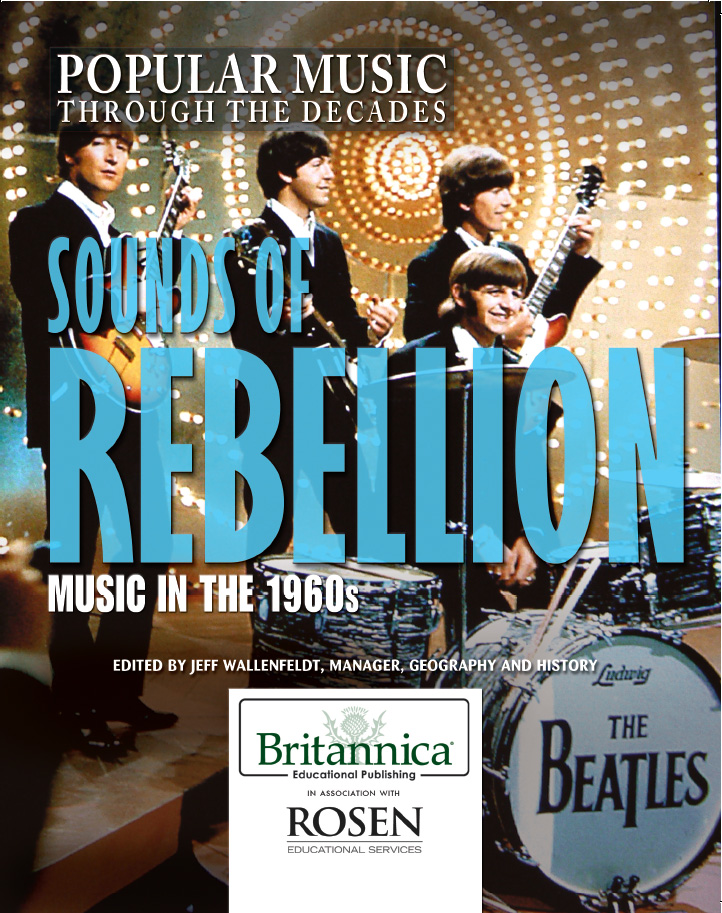

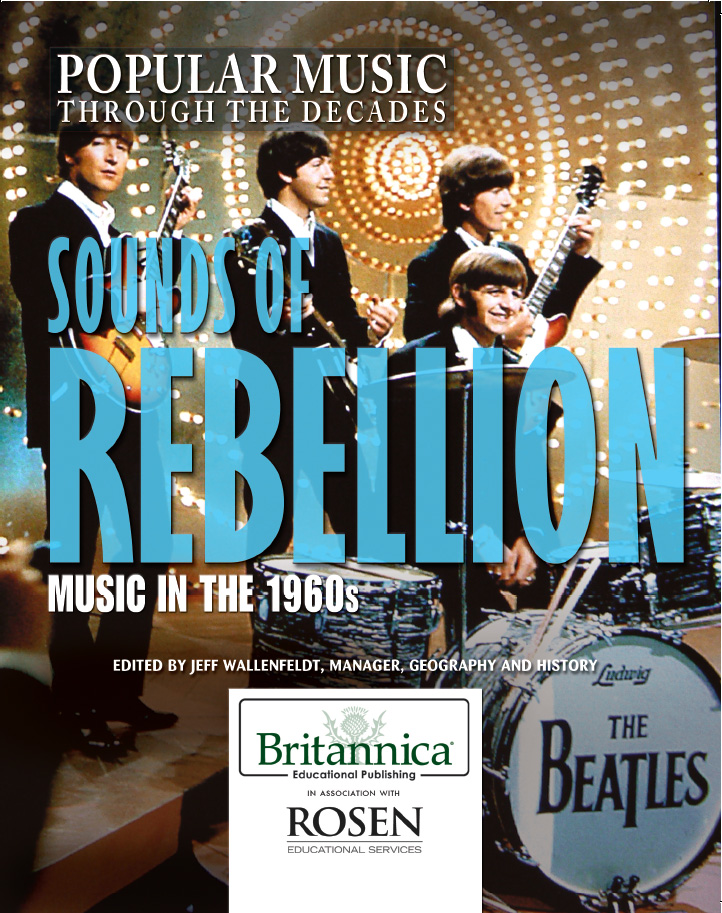

On the cover, p. iii: The Beatles performing on the British television show, Top of the Pops, in 1966. From left to right: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, and George Harrison. Ron Howard/Redferns/Getty Images

Pages 1, 13, 24, 32, 44, 60, 74, 89, 112, 124, 145, 168 Ethan Miller/Getty Images (Fender Stratocaster guitar), iStockphoto.com/catrinka81 (treble clef graphic); interior background image iStockphoto.com/hepatus; back cover iStockphoto.com/Vladimir Jajin

CONTENTS

A t more than eight minutes long, singer-songwriter Don McLeans American Pie was an unlikely hit on AM radio when it topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1972, yet for many teenagers at the time committing all six of the songs verses to memory was a rite of passage. Those lyrics offered a mythic explanation of some 10 tumultuous years in the history of the United States, the counterculture, and popular music, stretching roughly from rock-and-roll star Buddy Hollys death in a plane crash in 1959 to the debacle at the Altamont music festival helplessly presided over by the Rolling Stones in 1969. It was a period during which the rebelliousness that had been so central to early rock and roll returned after having disappeared at the end of the 1950s, when it was largely replaced by the sanitized pretty-boy pleasantness of teen icons such as Frankie Avalon and Fabian. The rebellion of 1950s rockers had seldom been articulated by them; it was more a matter of gesture, but gestures that meant everything. The embracement of black music and musicians and the adaptation of black musical styles by a growing number of white Americans had revolutionary implications. Rock-and-roll shows that attracted mixed blackand-white audiences were implicit sallies on segregation. But in the 1960s popular musics discontent with the status quo found its voice and became ideological, mirroring a generations assault on the politics, culture, and economics of post-World War II society.

The eras folk music revival was catalyzed by a group of clean-cut collegiate-looking guys in matching shirts (the Kingston Trio) who wowed Middle America with polished versions of traditional songs. In short order, however, the legion of newly minted folkies who strummed their acoustic guitars in Washington Square in New York City began to embrace the progressive political mission that was the legacy of the old left and the old folkies who had kept the fires of dissent burning in Greenwich Village during the McCarthy era and the early Cold War years. In the 1950s screen idol James Dean had embodied the emphatic but inchoate angst of generation of young people who felt something was wrong with the way they were expected to live, but he was a Rebel Without a Cause. In the 1960s, young people and musicians took up and spoke forcefully about a number of causes, beginning with the civil rights movement.

Bob Dylan (generally taken to be the jester in American Pie, who sings in a coat borrowed from James Dean and voice that came from you and me) became the darling of the folk revival by updating traditional song forms with poetically complex, politically infused lyrics that confronted the discrimination and duplicity in American society head on. He and others who shared his political concernsmost notably singing journalist Phil Ochsbecame protest singers. Dylan and Joan Baez performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial before the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his famous I Have a Dream speech during the March on Washington in 1963; later, Ochswhose opposition to the Vietnam War was legendaryhelped form the Youth International Party and was at the centre of Yippie demonstrations at the cataclysmic national convention of the Democratic Party in Chicago in 1968.

As the decade progressed, Dylan and American youth in general heard another clarion call, sounded from across the Atlantic by British beat groups who echoed the power of early American rock and roll. Liverpool, a once-majestic imperial port city in economic decline, was the home to hundreds of these groups. In an atmosphere of postwar austerity that had limited the leisure options for young Britons in the 1950s, skiffle music provided an exciting alternative. The material requirements were minimal: one or more acoustic guitars and a rudimentary bass, often fashioned from a broomstick attached to a tea chest. The music sources were American folk and blues. Lonnie Donegan, a member of a band that played traditional New Orleans-style jazz (Britains other great musical preoccupation at the time) became skiffles avatar when his rendition of American folk-blues singer Leadbellys Rock Island Line was a hit in 1954. The skiffle groups that sprang up across the United Kingdom began looking beyond folk and blues to rhythm and blues and early rock and roll for their sources. This was especially true in Liverpool, to which, according to the most romantic version of the movements origins, the Cunard Yanksthe stewards and those who worked on passenger shipsreturned from the United States with the latest R&B and rock-and-roll hit records, as well as electric guitars. Teenage Liverpudlian skiffle players, such as future Beatles John Lennon and Paul McCartney, fell in the thrall of Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Carl Perkins, and especially Buddy Holly, whose stylish but relatively straightforward guitar playing was imitable. The beat boom, the British reinvention of rock and roll, and the invasion of the United States by British groups were but a few hundred amplifiers away.