Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2011 by C.S. Fuqua

All rights reserved

Cover design by Natasha Momberger

First published 2011

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.348.0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fuqua, Christopher S., 1956

Alabama musicians : musical heritage from the heart of Dixie / C.S. Fuqua.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-157-4

1. Musicians--Alabama--Biography. I. Title.

ML385.F92 2-11

780.922761--dc23

[B]

2011027331

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Bonnie, Tegan, Yukio and Hideko; Janet and David; Rick, Michie, Kanako, Dick, Tonya, Beth and John; the Neo Epoque members; and all who love music.

Contents

About This Book

Alabamas contributions to music are broad and profound, from defining musical styles such as boogie-woogie and blues to providing major artists in every music genre and to developing and housing production studios that have become legendary. This books first section provides a brief history of the states musical regions and their contributions to music since the 1800s. The second section explores the lives of some of the major artists from the state.

Due to the vast accomplishments of Alabamians, readers may expect to find certain artists biographies included here only to discover that theyre not. The basic criterion for inclusion is that the artist, or at least a member of any included band, be a native Alabamian. Performers like Mississippi native Jimmy Buffett, Jamaica-born Eddie Kirkland, Florida native Bobby Goldsboro and Los Angeles native Debbie Bond are not included, even though theyre regularly associated with Alabama. If any nonnative artist deserves inclusion, its Debbie for her relentless promotion of Alabama music and musicians through the Alabama Blues Projects educational programs, concerts and CD releases. These artists would have been included, but due to project limitations, not even all Alabama native artists could be included. So dont stop your research of Alabamas musical contributions here. Visit the Alabama Blues Project, Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame and Alabama Music Hall of Fame websites for more complete lists of Alabama artists, including transplants, to help you on the way.

Much gratitude goes to the artists, photographers and organizations who have contributed directly to this project, including photo editor Peggy Collins and the Alabama Tourism Department, Alabama Blues Project, Birmingham Public Library, Alabama Music Hall of Fame, Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame and photographer Carol M. Highsmith for images from her Library of Congress America collection. I also thank The History Press and editors Will McKay and Hilary McCullough for initiating and supporting this project.

Alabamas Contributions to Music

EARLY HISTORY

Documenting Alabamas contributions to the world of music would have been delayed by decades had it not been for the efforts of a few individuals determined in the early to mid-1900s to preserve the states rich cultural heritage. One of those researchers was Ruby Pickens Tartt, who passionately collected Alabama slave stories, folklore and folk music, eventually becoming a valuable resource to the Library of Congress and guaranteeing that the states early musical achievements would not be lost to time.

Born in 1880 in Livingston, Tartt relished local African American culture, especially its robust music and storytelling. After graduating Alabama State Normal College, Tartt studied under William Merritt Chase at Chase School of Art in New York but returned to Alabama to marry William Pratt Tartt in 1904 and to work in the Tartt familys bank. She later formed a friendship with New York native Carl Carmer, who taught at the University of Alabama (UA). She regaled him with numerous tales of rural folk life and music that he later used as the basis for his novel, Stars Fell on Alabama, styling one of the books main characters on Tartt. But it wasnt until the Great Depression destroyed much of the Tartts wealth that Ruby began her work to preserve the rich musical culture she so loved.

Taking a job with the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal agency designed to put millions of Americans back to work, Tartt chaired the local Federal Writers Project that ran from 1936 to 1940, documenting life stories, folktales and folksongs of former slaves. This research garnered the attention of John A. Lomax, a Library of Congress ethnomusicologist. Although Newman I. White, an Alabama Polytechnic Institute instructor, had published in 1928 a collection of songs by Alabama African Americans, entitled American Negro Folk-Songs, most of the songs had come to him secondhand from white students who had learned them from African American acquaintances. It wasnt until Lomax solicited Tartts assistance that Alabamas authentic musical culture gained national recognition.

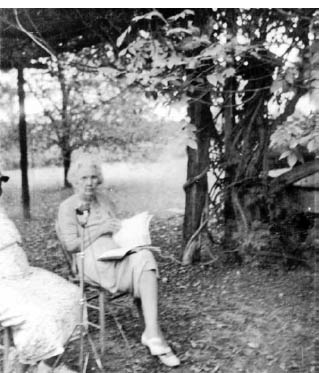

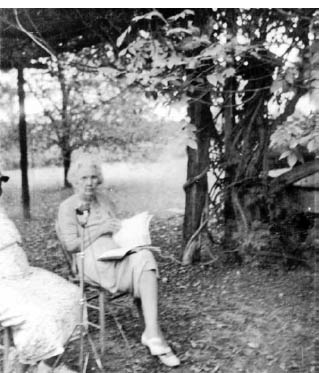

Ruby Pickens Tarrt. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Lomax Collection.

Tartt spent four years assisting Lomax in and around Sumter County, recording the voices and songs of convicts, schoolchildren and everyday folk, including Dock Reed and Vera Hall Ward, now considered two of the twentieth centurys greatest folk vocalists. Listeners around the world were introduced to those singers and Alabama music through Lomaxs ten-volume record set, The Ballad Hunter, and the British Broadcasting Corporation series of American folksong releases during the 1950s that included Tartts transcriptions of lyrics for the Sumter County songs. Lomax and his son Alan later featured other material recorded with Tartts help in the releases Afro-American Spirituals, Work Songs, and Ballads and Afro-American Blues and Game Songs.

In the 1940s, Tartt contracted with Houghton Mifflin to base a collection of short stories on local culture, but a tornado struck her home, destroying her research and severely injuring her right hand. Although she never completed the book, she assisted folklorist Harold Courlander in 1950 to record more Sumter County singers, who were included in the Folkways collections Rich Amerson I, Rich Amerson II, Folk Music U.S.A., Negro Folk Music of Alabama, Negro Songs of Alabama and Negro Folk Music U.S.A. Many of the songs appeared in subsequent collections and were covered by artists such as the Kingston Trio. Since Tartts death on November 29, 1974, new audiences have been introduced to early Alabama folk life through the songs, stories and lore that she collected.

In 1938, Byron Arnold, an Eastman School of Music of New York graduate, joined UAs music department and became enamored with African American preaching and singing and the musics cultural importance. While Tartt and Lomax concentrated efforts in and around Sumter County, Arnold explored music by black and white residents statewide. Then, in 1945, with UA Research Committee financial support, Arnold enlisted Tartts help and spent that summer touring the state to transcribe tunes and lyrics to paper. Even though he had no recording device, Arnold viewed the trip as a success, transcribing 258 folksongs.

Next page