2021 William A. Link

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Scala Sans, Payson, and Odon

by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

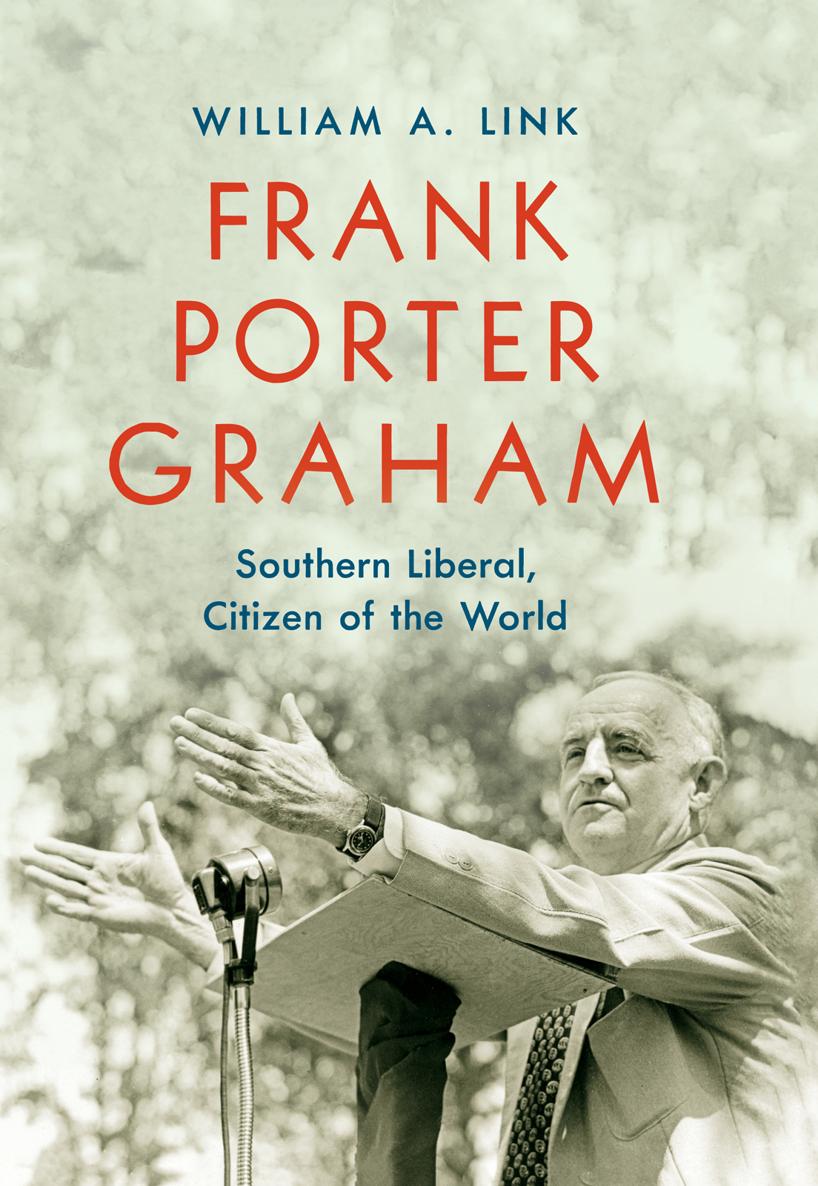

Cover photographs (front and back) courtesy of Wilson Special Collections Library, UNCChapel Hill; (spine) courtesy of The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Link, William A., author.

Title: Frank Porter Graham : southern liberal, citizen of the world / William A. Link.

Description: Chapel Hill : Published in association with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library by the University of North Carolina Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021844 | ISBN 9781469664934 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469664941 (ebook)

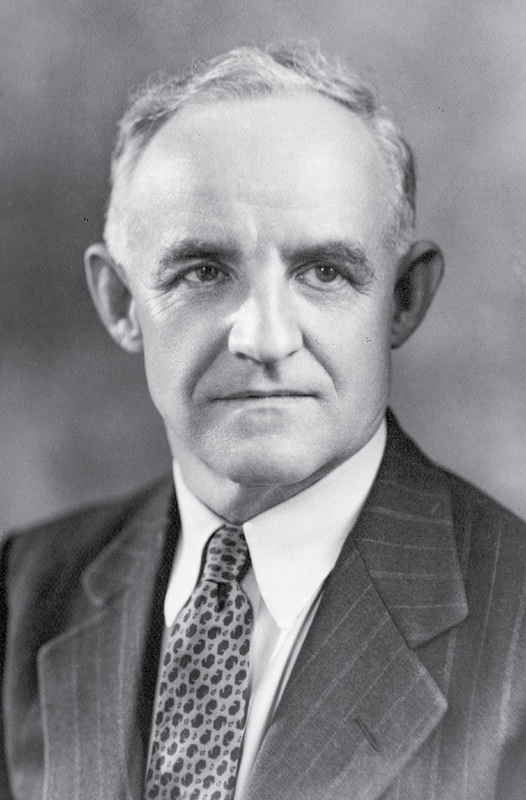

Subjects: LCSH: Graham, Frank Porter, 18861972. | University of North Carolina (17931962)History. | EducatorsNorth CarolinaBiography. | StatesmenNorth CarolinaBiography.

Classification: LCC F259.G7 L56 2021 | DDC 328.73/092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021844

Preface

My first exposure to Frank Porter Graham came in February 1972, when, as a high school senior from New Jersey, I visited the campus of the University of North Carolina. Both of my parents were UNC graduates and, though they spent most of their adult lives outside North Carolina, always considered the state their home. My mother grew up across the street from Davidson College, where her father taught physics for nearly half a century; although the campus remained an all-male institution until 1972, she attended Davidson for two years during the 1930s because the college, during the Depression, permitted faculty daughters to attend two years and then transfer to another college. Both of my parents thoroughly internalized regional loyalties and expected their children to abide by them. As a result, among the four children in my family, all of them attended either UNC or Davidson.

I happened to visit UNC just before Frank Graham passed away, and local headlines were filled with the news and tributes to his career. Having been students at UNC during the 1930s and 1940s, my parents were Graham admirers, but I had little idea who he was. I quickly learned, and he has fascinated me ever since. Subsequently, as a faculty member at UNC-Greensboro for twenty-three years, I learned more. So when Bob Anthony suggested the idea of a new Graham biography that would appear in the UNC Librarys Coates Leadership series, I was intrigued. I was also aware of the enormity of the subject. Grahams papers, at UNCs Southern Historical Collection, are vast. But also daunting is the intellectual challenge of placing Grahams life in the history of the university, state, region, and nation.

In 1990, Bill Friday observed that serving as UNC president was a much better position than being Governor of the state anytime because the job had a greater and more sustained impact on North Carolinians than any elective office. But UNC presidents, with this exaggerated public role, also had to maintain the confidence of state leaders and the general public. Far from shunning the spotlight, Graham sought out and cultivated editorial writers in the state in order to further the cause of education. He became a lifelong cheerleader for UNC, but he often tested public patience. Over time, Graham joined liberals who sought to ameliorate the effects of industrialization as well as racial segregation, and these causes expanded his public role beyond higher education. The university occupied a precarious position in the state, and many North Carolinians have long regarded Chapel Hill as a center of political and cultural radicalism. For the most part, Graham succeeded in fending off conservative critics who were aroused by controversial speakers who appeared on campus. He also enjoyed considerable freedom to take controversial positions, especially on labor and labor unions. Yet there were limits to how far Graham could push white North Carolinians on the highly sensitive topics of labor and race.

Another appeal of writing a Graham biography arises from my experience writing previous biographies, in which I narrate the lives of two important North Carolinians and white southerners, UNC president William C. Friday and five-term US senator Jesse Helms. Adding Graham to that mix creates a trilogy that encompasses modern North Carolina; the impact of these three men extended beyond the borders of the state, and their careers overlapped. In different ways, these three men came to define the rapid economic, cultural, and political history of North Carolina as well as of the modern South.

In North Carolina, as sociologist Paul Luebke reminds us, a struggle raged between traditionalists and modernizers. By the middle of the twentieth century, the state had become sharply polarized between those pushing for change and those opposing it. Education, especially higher education, played a central role in the modernizers agenda. At the same time, the small towns and countryside where most North Carolinians lived rebelled against what accompanied modernizationa widening gulf between urban and rural, between technology and its absence, and, perhaps most important, traditional Protestantism and growing secularization. Today and in its past, North Carolina displayed a stubborn resistance to change and a tension between modernizers and traditionalists that spurred political and cultural polarization. Social change has today widened the separation between modernizers and traditionalists, both powerful political forces in North Carolina. UNCs twentieth-century rise to global importance has exposed tensions that characterize early twenty-first century America.

While Friday was a modernizer, Helms came to be known as a defender of tradition. He is best known as US senator and one of the founders of the modern conservative movement. During most of his twenties, however, Helms was politically indifferent. Like Friday, he crossed paths with Graham during the 1940s. Jesse attended college for a few years without graduating and then worked during the 1940s as a Raleigh newspaperman and radio announcer. Moving to Raleigh, Helms fell in love with and married Dorothy Dot Coble in October 1942. As a UNC coed, she participated in the Sunday evening get-togethers that Graham held at the presidents house. One of the first women to graduate from the UNC School of Journalism, Dot often brought Jesse with her during return visits to Chapel Hill. Helms considered Graham a charming and dear man. But Helms had a choice to make when Graham sought his help in a special election for a US Senate seat in 1950, which became known as one of the most vitriolic in the states history. By then, Helms had become a dedicated conservative and opponent of most of what the UNC president stood for. Instead, Helms worked for Willis Smith, Grahams opponent.